Monday, August 01. 2011

How an argument with Hawking suggested the Universe is a hologram

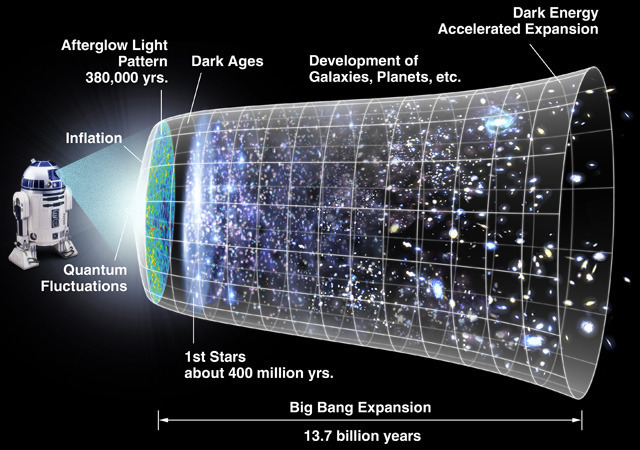

The proponents of string theory seem to think they can provide a more elegant description of the Universe by adding additional dimensions. But some other theoreticians think they've found a way to view the Universe as having one less dimension. The work sprung out of a long argument with Stephen Hawking about the nature of black holes, which was eventually solved by the realization that the event horizon could act as a hologram, preserving information about the material that's gotten sucked inside. The same sort of math, it turns out, can actually describe any point in the Universe, meaning that the entire content Universe can be viewed as a giant hologram, one that resides on the surface of whatever two-dimensional shape will enclose it.

That was the premise of panel at this summer's World Science Festival, which described how the idea developed, how it might apply to the Universe as a whole, and how they were involved in its development.

The whole argument started when Stephen Hawking attempted to describe what happens to matter during its lifetime in a balck hole. He suggested that, from the perspective of quantum mechanics, the information about the quantum state of a particle that enters a black hole goes with it. This isn't a problem until the black hole starts to boil away through what's now called Hawking radiation, which creates a separate particle outside the event horizon while destroying one inside. This process ensures that the matter that escapes the black hole has no connection to the quantum state of the material that had gotten sucked in. As a result, information is destroyed. And that causes a problem, as the panel described.

As far as quantum mechanics is concerned, information about states is never destroyed. This isn't just an observation; according to panelist Leonard Susskind, destroying information creates paradoxes that, although apparently minor, will gradually propagate and eventually cause inconsistencies in just about everything we think we understand. As panelist Leonard Susskind put it, "all we know about physics would fall apart if information is lost."

Unfortunately, that's precisely what Hawking suggested was happening. "Hawking used quantum theory to derive a result that was at odds with quantum theory," as Nobel Laureate Gerard t'Hooft described the situation. Still, that wasn't all bad; it created a paradox and "Paradoxes make physicists happy."

"It was very hard to see what was wrong with what he was saying," Susskind said, "and even harder to get Hawking to see what was wrong."

The arguments apparently got very heated. Herman Verlinde, another physicist on the panel, described how there would often be silences when it was clear that Hawking had some thoughts on whatever was under discussion; these often ended when Hawking said "rubbish." "When Hawking says 'rubbish,'" he said, "you've lost the argument."

t'Hooft described how the disagreement eventually got worked out. It's possible, he said, to figure out how much information has gotten drawn in to the black hole. Once you do that, you can see that the total amount can be related to the surface area of the event horizon, which suggested where the information could be stored. But since the event horizon is a two-dimensional surface, the information couldn't be stored in regular matter; instead, the event horizon forms a hologram that holds the information as matter passes through it. When that matter passes back out as Hawking radiation, the information is restored.

Susskind described just how counterintuitive this is. The holograms we're familiar with store an interference pattern that only becomes information we can interpret once light passes through them. On a micro-scale, related bits of information may be scattered far apart, and it's impossible to figure out what bit encodes what. And, when it comes to the event horizon, the bits are vanishingly small, on the level of the Planck scale (1.6 x 10-35 meters). These bits are so small, as t'Hooft noted, that you can store a staggering amount of information in a reasonable amount of space—enough to describe all the information that's been sucked into a black hole.

The price, as Susskind noted, was that the information is "hopelessly scrambled" when you do so.

From a black hole to the Universe

Berkeley's Raphael Bousso was on hand to describe how these ideas were expanded out to encompass the Universe as a whole. As he put it, the math that describes how much information a surface can store works just as well if you get rid of the black hole and event horizon. (This shouldn't be a huge surprise, given that most of the Universe is far less dense than the area inside a black hole.) Any surface that encloses an area of space in this Universe has sufficient capacity to describe its contents. The math, he said, works so well that "it seems like a conspiracy."

To him, at least. Verlinde pointed out that things in the Universe scale with volume, so it's counterintuitive that we should expect its representation to them to scale with a surface area. That counterintuitiveness, he thinks, is one of the reasons that the idea has had a hard time being accepted by many.

When it comes to the basic idea—the Universe can be described using a hologram—the panel was pretty much uniform, and Susskind clearly felt there was a consensus in its favor. But, he noted, as soon as you stepped beyond the basics, everybody had their own ideas, and those started coming out as the panel went along. Bousso, for example, felt that the holographic principle was "your ticket to quantum gravity." Objects are all attracted via gravity in the same way, he said, and the holographic principle might provide an avenue for understanding why (if he had an idea about how, though, he didn't share it with the audience). Verlinde seemed to agree, suggesting that, when you get to objects that are close to the Planck scale, gravity is simply an emergent property.

But t'Hooft seemed to be hoping that the holographic principle could solve a lot more than the quantum nature of gravity—to him, it suggested there might be something underlying quantum mechanics. For him, the holographic principle was a bit of an enigma, since disturbances happen in three dimensions, but propagate to a scrambled two-dimensional representation, all while obeying the Universe's speed limit (that of light). For him, this suggests there's something underneath it all, and he'd like to see it be something that's a bit more causal than the probabilistic world of quantum mechanics; he's hoping that a deterministic world exists somewhere near the Planck scale. Nobody else on the panel seemed to be all that excited about the prospect, though.

What was missing from the discussion was an attempt to tackle one of the issues that plagues string theory: the math may all work out and it could provide a convenient way of looking at the world, but is it actually related to anything in the actual, physical Universe? Nobody even attempted to tackle that question. Still, the panel did a good job of describing how something that started as an attempt to handle a special case—the loss of matter into a black hole—could provide a new way of looking at the Universe. And, in the process, how people could eventually convince Stephen Hawking he got one wrong.

Friday, July 29. 2011

Just How Dangerous Is Facial Profiling?

Via BigThink

-----

Within the next 60 days, state law enforcement agencies across the nation are set to implement a new facial profiling technologythat will enable them to scan faces of people in a crowd and cross-check this scan data with information already in their databases. Simply by equipping a so-called MORIS ("Mobile Offender Recognition and Information System") device to an iPhone, it will be possible to scan faces from as far as five feet away and perform iris scans at distances of six inches or less. The same technology that makes it possible to spot an Al Qaeda insurgent in Afghanistan or nab a suspected terrorist in New York City also makes it possible to nab an undocumented migrant worker in El Paso or Laredo. And therein lies the problem.

Facial profiling is, if not used properly, as dangerous to our privacy and civil liberties as racial profiling. Which faces will police officers scan in a crowd? And when do law enforcement agents have the right to scan your irises? Having your iris scanned, as some have suggested, is tantamount to being fingerprinted in public – and potentially, without you even knowing about it. Of course, as Emily Steel and Julia Angwin point out in the Wall Street Journal, taking photos of people passing through a public space is fully enabled by law. And it’s perfectly acceptable for a law enforcement to stop and detain someone if they have “reasonable suspicion” that a crime has been committed - or is about to be committed.

But what if they just don’t like your face? (Maybe you forgot to shave that morning, and your ironic hipster beard is starting to look a little too much like an Osama beard.)

Getting stopped and detained raises a whole host of other legal questions related to search-and-seizure. Do you have the right to resist an iris scan if you have been detained? Thus far, the courts have not yet had to rule on face- and iris-recognition technology. But, as law professor Orin Kerr from George Washington University points out, "A warrant might be required to force someone to open their eyes."

It’s perfectly possible that Facial Profiling by law enforcement authorities will cause a civil libertarian uproar. Just think of the TSA pat-down procedures at airports. How many of us enjoy getting a little extra grope on the way to our planes? If we think full-body scanners are invasive enough, what about a bunch of Bad Lieutenants in Arizona having a little fun with their new iPhone toy?

Every time a technology company comes up with an innovative new way to “protect” us, we move further into a civil liberties gray area. Nearly a decade ago, when Oracle announced plans for a national ID card, Larry Ellison came under a firestorm of commentary. Even as recently as the past 18 months, when companies like Facebook and Google have developed new facial recognition technologies that enable us to "tag" our friends in photos, there has been murmurs of dissent from privacy and civil libertarian activists.

At the end of the day, facial recognition technology doesn't profile people, people do. Some would argue that the more that law enforcement authorities know about us, the freer we are. They will be better able to protect us from the evil forces of Al Qaeda circulating in our midst. Yet, at some level, that argument begins to sound a bit Orwellian. War is Peace. Freedom is Slavery. Ignorance is Strength. So just how dangerous is facial profiling?

New Geographic Data Analysis Gives Historians a Futuristic Window Into the Past

Via POPSCI

By Rebecca Boyle

-----

"Spatial humanities," the future of history

Even using the most detailed sources, studying history often requires a great imagination, so historians can visualize what the past looked and felt like. Now, new computer-assisted data analysis can help them really see it.

Geographic Information Systems, which can analyze information related to a physical location, are helping historians and geographers study past landscapes like Gettysburg, reconstructing what Robert E. Lee would have seen from Seminary Ridge. Researchers are studying the parched farmlands of the 1930s Dust Bowl, and even reconstructing scenes from Shakespeare’s 17th-century London.

But far from simply adding layers of complexity to historical study, GIS-enhanced landscape analysis is leading to new findings, the New York Times reports. Historians studying the Battle of Gettysburg have shed light on the tactical decisions that led to the turning point in the Civil War. And others examining records from the Dust Bowl era have found that extensive and irresponsible land use was not necessarily to blame for the disaster.

GIS has long been used by city planners who want to record changes to the landscape over time. And interactive map technology like Google Maps has led to several new discoveries. But by analyzing data that describes the physical attributes of a place, historians are finding answers to new questions.

Anne Kelly Knowles and colleagues at Middlebury College in Vermont culled information from historical maps, military documents explaining troop positions, and even paintings to reconstruct the Gettysburg battlefield. The researchers were able to explain what Robert E. Lee could and could not see from his vantage points at the Lutheran seminary and on Seminary Hill. He probably could not see the Union forces amassing on the eastern side of the battlefield, which helps explain some of his tactical decisions, Knowles said.

Geoff Cunfer at the University of Saskatchewan studied a trove of data from all 208 affected counties in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma and Kansas — annual precipitation reports, wind direction, agricultural censuses and other data that would have been impossible to sift through without the help of a computer. He learned dust storms were common throughout the 19th century, and that areas that saw nary a tiller blade suffered just as much.

The new data-mapping phenomenon is known as spatial humanities, the Times reports. Check out their story to find out how advanced technology is the future of history.

Thursday, July 28. 2011

Decoding DNA With Semiconductors

Via New York Times

By Christopher Capozziello

-----

The inventor Jonathan Rothberg with a semiconductor chip used in the Ion Torrent machine.

The inventor of a new machine that decodes DNA with semiconductors has used it to sequence the genome of Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, a leading chip maker.

The inventor, Jonathan Rothberg of Ion Torrent Systems in Guilford, Conn., is one of several pursuing the goal of a $1,000 human genome, which he said he could reach by 2013 because his machine is rapidly being improved.

“Gordon Moore worked out all the tricks that gave us modern semiconductors, so he should be the first person to be sequenced on a semiconductor,” Dr. Rothberg said.

At $49,000, the new DNA decoding device is cheaper than its several rivals. Its promise rests on the potential of its novel technology to be improved faster than those of machines based on existing techniques.

Manufacturers are racing to bring DNA sequencing costs down to the point where a human genome can be decoded for $1,000, the sum at which enthusiasts say genome sequencing could become a routine part of medical practice.

But the sequencing of Dr. Moore’s genome also emphasizes how far technology has run ahead of the ability to interpret the information it generates.

Dr. Moore’s genome has a genetic variant that denotes a “56 percent chance of brown eyes,” one that indicates a “typical amount of freckling” and another that confers “moderately higher odds of smelling asparagus in one’s urine,” Dr. Rothberg and his colleagues reported Wednesday in the journal Nature. There are also two genetic variants in Dr. Moore’s genome said to be associated with “increased risk of mental retardation” — a risk evidently never realized. The clinical value of this genomic information would seem to be close to nil.

Dr. Rothberg said he agreed that few genes right now yield useful genetic information and that it will be a 10- to 15-year quest to really understand the human genome. For the moment his machine is specialized for analyzing much smaller amounts of information, like the handful of genes highly active in cancer.

The Ion Torrent machine requires only two hours to sequence DNA, although sample preparation takes longer. The first two genomes of the deadly E. coli bacteria that swept Europe in the spring were decoded on the company’s machines.

The earliest DNA sequencing method depended on radioactivity to mark the four different units that make up genetic material, but as the system was mechanized, engineers switched to fluorescent chemicals. The new device is the first commercial system to decode DNA directly on a semiconductor chip and to work by detecting a voltage change, rather than light.

About 1.2 million miniature wells are etched into the surface of the chip and filled with beads holding the DNA strands to be sequenced. A detector in the floor of the well senses the acidity of the solution in each well, which rises each time a new unit is added to the DNA strands on the bead. The cycle is repeated every few seconds until each unit in the DNA strand has been identified.

Several years ago, Dr. Rothberg invented another DNA sequencing machine, called the 454, which was used to sequence the genome of James Watson, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA. Dr. Rothberg said he was describing how the machine had “read” Dr. Watson’s DNA to his young son Noah, who asked why he did not invent a machine to read minds.

Dr. Rothberg said he began his research with the idea of making a semiconductor chip that could detect an electrical signal moving across a slice of neural tissue. He then realized the device he had developed was more suited to sequencing DNA.

George Church, a genome technologist at the Harvard Medical School, said he estimated the cost to sequence Dr. Moore’s genome at $2 million. This is an improvement on the $5.7 million it cost in 2008 to sequence Dr. Watson’s genome on the 454 machine, but not nearly as good as the $3,700 spent by Complete Genomics to sequence Dr. Church’s genome and others in 2009.

Dr. Rothberg said he had already reduced the price of his chips to $99 from $250, and today could sequence Dr. Moore’s genome for around $200,000. Because of Moore’s Law — that the number of transistors placeable on a chip doubles about every two years — further reductions in the cost of the DNA sequencing chip are inevitable, Dr. Rothberg said.

Stephan Schuster, a genome biologist at Penn State, said his two Ion Torrent machines were “outstanding,” and enabled a project that would usually have taken two months to be completed in five days.

There is now “a race to the death as to who can sequence faster and cheaper, always with the goal of human resequencing in mind,” Dr. Schuster said.

Wednesday, July 27. 2011

Volume of data darn near indescribable ...

Via Network World

-----

The world's digital data is doubling every two years and the amount created or replicated in 2011 will reach 1.8 zettabytes, a pile so gargantuan that its size can only be rendered understandable to the layman when translated into iPads.

That's right, words no longer suffice; we need something magical for this job.

The problem is presented in a press release touting the fifth annual IDC Digital Universe study, sponsored by EMC. A bar chart, right, and enormous infographic at the bottom of this post will give you an overview of the study's findings. Here we're going to try to get our minds around 1.8 zettabytes. The sentences in bold are from the press release.

In terms of sheer volume, 1.8 zettabytes of data is equivalent to:

Every person in the United States tweeting 3 tweets per minute for 26,976 years nonstop.

The trouble here is that even if you know the population of the United States (311 million, give or take) and the length of a tweet (140 characters, maximum) you're still left to plug those pieces into a length of time (26,976 years) that has no meaning to most anyone not a paleontologist.

Every person in the world having over 215 million high-resolution MRI scans per day.

Don't worry, I looked it up for you; the world has almost 7 billion people. And while I haven't the foggiest notion as to how much data would be represented by a single high-resolution MRI scan, never mind 215 million of them, I can tell you based on recent experience that the so-called "open MRI machines" are really not all that open.

Over 200 billion HD movies (each 2 hours in length) - Would take 1 person 47 million years to watch every movie.

Honestly, that one doesn't help at all.

But look what happens when the study's authors use their handy-dandy zettabyte-to-iPad translator:

The amount of information needed to fill 57.5 billion 32GB Apple iPads. With that many iPads we could:

Create a wall of iPads, 4,005-miles long and 61-feet high extending from Anchorage, Alaska to Miami, Florida.

There's a map of the United States, and there's a wall of iPads about 10 times my height.

Build a mountain 25-times higher than Mt. Fuji.

You don't even need to know the elevation of the mountain (12,388 feet) to form that mental picture.

Cover 86% of Mexico City.

Take a big city, cover almost all of it with iPads. Got it.

Build the Great iPad Wall of China - at twice the average height of the original.

Bet that baby would be visible from space.

Yes, yes, I understand that this exercise need not be about the iPad at all and that any old 9.5-by-7.31-by-.34-inch box packing 32 GB would do. But what picture of what tablet has been seared into your brain by two-plus years of Apple marketing?

I mean they used to use the Library of Congress for these types of comparisons. Libraries don't stack as well.

(Disclaimer: All of the math here belongs to IDC and EMC; blame me not for any errors.)

Tuesday, July 26. 2011

Former Google CIO: LimeWire Pirates Were iTunes' Best Customers

Via TorrentFreak

-----

Delivering his keynote address at this week’s annual CA Expo in Sydney, former Google CIO Douglas C Merrill added to the growing belief that punishing and demonizing file-sharers is a bad idea. Merrill, who after his Google stint joined EMI records, revealed that his profiling research at the label found that LimeWire pirates were iTunes’ biggest customers.

Yesterday, during his keynote speech at the CA Expo in Sydney, former Google boss Douglas C Merrill said that companies stuck in the past risk becoming irrelevant. He also had some very interesting things to say about pirates.

Merrill, who was Chief Information Officer and Vice President of Engineering at Google, left the search giant in 2008 after being poached by EMI, a key member label of the RIAA.

At EMI he took up the impressive position of Chief Operating Officer of New Music and President of Digital Business, despite admitting this week that he knew the music industry was “collapsing”.

“The RIAA said it isn’t that we are making bad music, but the ‘dirty file sharing guys’ are the problem,” he said during his speech as quoted by ComputerWorld.

“Going to sue customers for file sharing is like trying to sell soap by throwing dirt on your customers.”

But those “dirty file-sharing guys” had an even dirtier secret. During his stint at EMI, Merrill profiled the behavior of LimeWire users and discovered something rather interesting. Those same file-sharing “thieves” were also iTunes’ biggest spenders.

“That’s not theft, that’s try-before-you-buy marketing and we weren’t even paying for it… so it makes sense to sue them,” Merrill said, while undoubtedly rolling his eyes.

That same “try-before-you-buy” discovery was echoed in another study we reported on last week which found that users of pirate sites, including the recently-busted Kino.to, buy more DVDs, visit the cinema more often and on average spend more at the box office than their ‘honest’ counterparts.

Merrill’s words yesterday are not the only pragmatic file-sharing related comments he’s made in recent years. Almost immediately after his 2008 EMI appointment, he made comments which didn’t necessarily tow the company line.

“For example, there’s a set of data that shows that file sharing is actually good for artists. Not bad for artists. So maybe we shouldn’t be stopping it all the time. I don’t know,” Merrill said.

“Obviously, there is piracy that is quite destructive but again I think the data shows that in some cases file sharing might be okay. What we need to do is understand when is it good, when it is not good…Suing fans doesn’t feel like a winning strategy,” he concluded.

Less than a year later, Merrill was forced out by EMI.

Tuesday, July 19. 2011

Study Finds That Memory Works Differently in the Age of Google

-----

The rise of Internet search engines like Google has changed the way our brain remembers information, according to research by Columbia University psychologist Betsy Sparrow published July 14 in Science.

“Since the advent of search engines, we are reorganizing the way we remember things,” said Sparrow. “Our brains rely on the Internet for memory in much the same way they rely on the memory of a friend, family member or co-worker. We remember less through knowing information itself than by knowing where the information can be found.”

Sparrow’s research reveals that we forget things we are confident we can find on the Internet. We are more likely to remember things we think are not available online. And we are better able to remember where to find something on the Internet than we are at remembering the information itself. This is believed to be the first research of its kind into the impact of search engines on human memory organization.

Sparrow’s paper in Science is titled, “Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips.” With colleagues Jenny Liu of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Daniel M. Wegner of Harvard University, Sparrow explains that the Internet has become a primary form of what psychologists call transactive memory—recollections that are external to us but that we know when and how to access.

The research was carried out in four studies.

First, participants were asked to answer a series of difficult trivia questions. Then they were immediately tested to see if they had increased difficulty with a basic color naming task, which showed participants words in either blue or red. Their reaction time to search engine-related words, like Google and Yahoo, indicated that, after the difficult trivia questions, participants were thinking of Internet search engines as the way to find information.

Second, the trivia questions were turned into statements. Participants read the statements and were tested for their recall of them when they believed the statements had been saved—meaning accessible to them later as is the case with the Internet—or erased. Participants did not learn the information as well when they believed the information would be accessible, and performed worse on the memory test than participants who believed the information was erased.

Third, the same trivia statements were used to test memory of both the information itself and where the information could be found. Participants again believed that information either would be saved in general, saved in a specific spot, or erased. They recognized the statements which were erased more than the two categories which were saved.

Fourth, participants believed all trivia statements that they typed would be saved into one of five generic folders. When asked to recall the folder names, they did so at greater rates than they recalled the trivia statements themselves. A deeper analysis revealed that people do not necessarily remember where to find certain information when they remember what it was, and that they particularly tend to remember where to find information when they can’t remember the information itself.

According to Sparrow, a greater understanding of how our memory works in a world with search engines has the potential to change teaching and learning in all fields.

“Perhaps those who teach in any context, be they college professors, doctors or business leaders, will become increasingly focused on imparting greater understanding of ideas and ways of thinking, and less focused on memorization,” said Sparrow. “And perhaps those who learn will become less occupied with facts and more engaged in larger questions of understanding.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Columbia’s department of psychology.

Betsy Sparrow talks about her research, which examines the changing nature of human memory.

Wednesday, July 13. 2011

Guerrilla Educators Taking Over the Urban Classroom

Via Big Think

-----

In Milwaukee, the fourth-poorest city in America, educators have launched a "guerrilla classroom" initiative that transforms urban locations into impromptu classrooms for parents and children. Across Milwaukee, playgrounds, bus stops and parks now feature interactive displays and game-like learning environments that encourage interactions between parents and children and teach real-world applications of classroom subjects. It's all part of a pro bono marketing effort by marketing agency Cramer-Krasselt, Milwaukee Public Schools and COA Youth & Family Centers to raise awareness about the positive impact of involving parents in the education process. If successful, it's easy to see how similar groups of determined "guerrilla educators" could extend this approach to other cities.

The notion of the guerrilla classroom, of course, is an offshoot of guerrilla marketing, which in turn, is a capitalist expropriation of old school guerrilla warfare tactics. The basic idea of any guerrilla marketing campaign, of course, is to hit people with low-cost marketing and advertising messages in the places where they least expect. Realizing that we're saturated with advertising messages across TV, billboards and print publications, guerrilla marketers solve for this problem by taking to the streets. Literally. It could involve anything from elaborate PR stunts in public places to street teams of young teens handing out cold drink samples on a hot summer day. The best guerrilla marketing campaigns, of course, are those in which we are so totally ambushed don't even realize that we're being marketed to.

That's the brilliance of the Guerrilla Classroom initiative

- if it goes according to plan, these impromptu classrooms across the

city will draw in parents and children naturally. Waiting for that bus

for 15 minutes? Why not learn a little about mathematics while you wait?

Hanging out at the park? Why not take a minute to play a few little

word games that will help you read better? It's a well-known fact that

the greater the involvement of parents in the education process, the

better the results. The involvement doesn't have to occur at home or in a

formal classroom environment - it can now happen anywhere in the city,

at any time.

The Guerrilla Classroom initiative goes beyond the standard PSA message

that you might find around a city. These are not messages on

billboards telling parents and kids what to do -- these are

mini-classroom learning elements, distributed around the city. As a

result, the Guerrilla Classroom concept hits at one of the central

problems facing the urban parent: too little time to get involved in

the educational process. This is a depressing truth at both ends of the

socio-economic spectrum: minimum-wage workers are working too many

hours and multiple jobs to make ends meet, while urban elite parents

are typically too busy following their career and social-climbing goals

to spend quality one-on-one time with their kids.

Innovators now have a host of new tools - from mobile devices to the latest thinking about game mechanics - to extend this concept of the Guerrilla Classroom and reach an even-wider audience. Based on the early success of the Skillshare model, for example, it's not hard to imagine a day when small "flash mobs" of kids decide to meet up all over the city in "cool" places like skate parks to teach each other foreign languages, music, painting, or even more fundamental things - like how to cope with parents who suddenly have shown a much greater interest in their educational development.

Tuesday, July 12. 2011

Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) program

Via keirthomas.com (by Keir Thomas)

-----

There’s been a lot of fuss recently about $0.99 Kindle eBooks.

Essentially, ‘publishers’ are buying-in cheap content and packaging it into eBooks that they sell through the Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) program for $0.99. KDP lets anybody create and list a Kindle eBook for free. All you need is an Amazon account.

Amazon check all eBooks for quality but that’s to make sure things like layout are acceptable. They don’t really care what the content is, provided it fits within acceptability guidelines. Quite rightly too. Who are they to be censors or arbiters? And how could they even find time to read each book?

Giving it a try

As part of my regular but foolish publishing experiments, I put some $0.99 computer books on sale though KDP in March 2011 — Working at the Ubuntu Command-Line, and font-size: 14px; font-style: italic; font-weight: 400; line-height: 17px;" class="style"> Managing the Ubuntu Software System. Mine contain content written by myself, however, and not bought-in or culled from the web.

So does $0.99 publishing work, at least when it comes to computer books?

Yes and no. Did you really expect a straight answer?

Do it right* and you’ll sell thousands of copies. Working at the Ubuntu Command-Line is usually glued to the top of the Amazon best-seller charts for Linux and also for Operating Systems.

Something I’ve created all on my lonesome is besting efforts by publishing titans like O’Reilly, Prentice Hall, Wiley, and others.

Admittedly, a new release of Ubuntu came along in April. That helped. However, my Excel charts show sales of my eBooks ramping up, rather than tailing off now the hype about that release is over.

(It’s tempting to think of publishing a book as like exploding a bomb, in that sales die down after an initial peak. The truth is it’s more like a crescendo as the book slowly builds-up a reputation, along with those all-important Amazon reviews.)

Making money

But... You’re not going to make a huge amount of money. The royalty on a $0.99 book is $0.35. If you sell 1,000 copies, you’re going to make $350. The people who make a fortune at this are turning over 500,000 copies of their $0.99 eBooks.

I hear that Amazon frowns on the whole $0.99 eBook thing, and that critics are calling for the zero entry-barrier of KDP to be removed. They suggest Amazon charge a listing fee for each book — perhaps $10 or $20. This would limit the scams mentioned above.

This would be a huge shame. Through things like KDP and CreateSpace, Amazon is making proper publishing truly democratic and accessible to all. To get a Kindle eBook on sale, all you need is a computer with a word processor. That’s it. You don’t need up-front fees. You don’t need to be a publisher. You don’t need technical knowledge.

If you don’t believe that’s mind-blowing then, well, I feel sorry for you.

Check your sources

If you hear people campaigning against KDP, check-out their background. Are they authors who are listed with major publishers? Are they publishers themselves? It’s in the interest of anybody involved in traditional publishing to stop things like KDP in its tracks.

KDP is a dangerous thing. That’s why it’s so good. I’d like to see more companies offer services like KDP. Can you imagine what it’d be like if a major publisher embraced a similar concept?

The only bad thing from my perspective is that sales of my self-published Ubuntu book have dropped like a stone. This corroborates my theory that there’s only a set of amount of users and money within the Ubuntu ecosystem. But that’s a topic for another time.

Incidentally, if you’re interested in computer eBooks, check out WalrusInk.

* ‘Doing it right’ includes having high-quality content, correctly laid-out in the book, and putting together a professional cover. Having a good author background helps too. If the cover look like it’s designed in MS Paint and the author neglects to provide a biography in the blurb, you should know what to expect.

Thursday, June 30. 2011

Is the Internet an Inalienable Right?

Via Big Think

-----

With the arrival of the July 4th weekend, now is a good time to consider the types of individual rights that the U.S. constitution continues to make possible, even against the backdrop of a rapidly-changing information-based society. We have the freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly - but do we also have the freedom to connect in a mobile, networked world? Does the Internet already encompass many of the fundamental rights outlined by our Founding Fathers, or is the Freedom to Connect a new type of inalienable right?

As TIME magazine points out in its cover story on the U.S. Constitution (One Document, Under Seige),

the Founding Fathers could never have even imagined a whole host of

modern innovations – including, but not limited to, the modern-day

Internet: "George Washington didn't even dream that man could fly, much

less use a global-positioning satellite to aim a missile, so it's

hard to say what he would think." So, the question is not how the

Founding Fathers would have felt about the Internet, but rather,

whether the documents they created were flexible enough to accommodate

for the phenomenal growth of the Internet and its impact on every facet

of our lives, both here in America and globally.

In the wake of the popular uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia and across the Middle East, it is clear that the Internet represents more than just economic empowerment - it is a fundamental underpinning of a democratic society. As Secretary of State Hillary Clinton outlined in her “Freedom to Connect” policy speech on Internet freedom, “an open Internet fosters long-term peace, progress and prosperity.” And a closed Internet? The consequences are almost too dire to consider: “An Internet that is closed and fractured, where different governments can block activity or change the rules on a whim—where speech is censored or punished, and privacy does not exist—that is an Internet that can cut off opportunities for peace and progress and discourage innovation and entrepreneurship.”

While we consider the Internet to be fundamental to the flowering of

democracy abroad, what about here in America? The Founding Fathers could

never have imagined an Internet "Kill Switch" bill passing through the

Congress, or the government-mandated seizure of domain names, or the

decision of the government to selectively shut down certain parts of the

Internet. They also could never have imagined Wiki-Leaks or Anonymous

or LulzSec, and the limits to what type of information governments

should have to divulge.

At a time when the Internet makes possible so many economic and social benefits that derive from a networked society, we sometimes forget just how important “the Internet” – including access to our mobile devices - is to the way we communicate, share and demonstrate our democratic values. People sometimes talk about the Internet as a commodity, as if it were something like electricity or water or air. In an era of Internet Kill Switches, the ability to "shut down" the Internet would be like turning off our water supply.

The “freedom to connect” in America needs to be held to a higher standard than we hold it elsewhere in the world. Given the role that the Internet plays in our everyday lives and the way it helps to distribute information and data, we need to be vigilant when elected U.S. government officials start talking about taking away our fundamental right to the Internet, or when leaders in Silicon Valley begin to acquiesce in the face of government requests to censor or limit information. At some point, We The People becomes We the Internet.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131057)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101672)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100067)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57901)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57463)

Categories

Show tagged entries

Syndicate This Blog

Calendar

|

|

February '26 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |