Tuesday, November 08. 2011

The Big Picture: True Machine Intelligence & Predictive Power

-----

At the beginning of last week, I launched GreedAndFearIndex - a SaaS platform that automatically reads thousands of financial news articles daily to deduce what companies are in the news and whether financial sentiment is positive or negative.

It’s an app built largely on Scala, with MongoDB and Akka playing prominent roles to be able to deal with the massive amounts of data on a relatively small and cheap amount of hardware.

The app itself took about 4-5 weeks to build, although the underlying technology in terms of web crawling, data cleansing/normalization, text mining, sentiment analysis, name recognition, language grammar comprehension such as subject-action-object resolution and the underlying “God”-algorithm that underpins it all took considerably longer to get right.

Doing it all was not only lots of late nights of coding, but also reading more academic papers than I ever did at university, not only on machine learning but also on neuroscience and research on the human neocortex.

What I am getting at is that financial news and sentiment analysis might be a good showcase and the beginning, but it is only part of a bigger picture and problem to solve.

Unlocking True Machine Intelligence & Predictive Power

The

human brain is an amazing pattern matching & prediction machine -

in terms of being able to pull together, associate, correlate and

understand causation between disparate, seemingly unrelated strands of

information it is unsurpassed in nature and also makes much of what has

passed for “Artificial Intelligence” look like a joke.

However, the human brain is also severely limited: it is slow, it’s immediate memory is small, we can famously only keep track of 7 (+-) things at any one time unless we put considerable effort into it. We are awash in amounts of data, information and noise that our brain is evolutionary not yet adapted to deal with.

So the bigger picture of what I’m working on is not a SaaS sentiment analysis tool, it is the first step of a bigger picture (which admittedly, I may not solve, or not solve in my lifetime):

What if we could make machines match our own ability to find patterns based on seemingly unrelated data, but far quicker and with far more than 5-9 pieces of information at a time?

What if we could accurately predict the movements of financial markets, the best price point for a product, the likelihood of natural disasters, the spreading patterns of infectious diseases or even unlock the secrets of solving disease and aging themselves?

The Enablers

I see a number of enablers that are making this future a real possibility within my lifetime:

- Advances in neuroscience: our understanding of the human brain is getting better year by year, the fact that we can now look inside the brain on a very small scale and that we are starting to build a basic understanding of the neocortex will be the key to the future of machine learning. Computer Science and Neuroscience must intermingle to a higher degree to further both fields.

- Cloud Computing, parallelism & increased computing power: Computing power is cheaper than ever with the cloud, the software to take advantage of multi-core computers is finally starting to arrive and Moore’s law is still advancing at ever (the latest generation of MacBook Pro’s have roughly 2.5 times the performance of my barely 2 year old MBP).

- “Big Data”: we have the data needed to both train and apply the next generation of machine learning algorithms on abundantly available to us. It is no longer locked away in the silos of corporations or the pages of paper archives, it’s available and accessible to anyone online.

- Crowdsourcing: There are two things that are very time intensive when working with machine learning - training the algorithms, and once in production, providing them with feedback (“on the job training”) to continually improve and correct. The internet and crowdsourcing lowers the barriers immensely. Digg, Reddit, Tweetmeme, DZone are all early examples of simplistic crowdsourcing with little learning, but where participants have a personal interest in participating in the crowdsourcing. Combine that with machine learning and you have a very powerful tool at your disposal.

Babysteps & The Perfect Storms

All

things considered, I think we are getting closer to the perfect storm of

taking machine intelligence out of the dark ages where they have

lingered far too long and quite literally into a brave new world where

one day we may struggle to distinguish machine from man and artificial

intelligence from biological intelligence.

It will be a road fraught with setbacks, trial and error where the

errors will seem insurmountable, but we’ll eventually get there one

babystep at a time.

I’m betting on it and the first natural step is

predictive analytics & adaptive systems able to automatically detect

and solve problems within well-defined domains.

Tuesday, November 01. 2011

Multi-Device Web Design: An Evolution

Via LUKEW

By Luke Wroblewski

-----

As mobile devices have continued to evolve and spread, so has the process of designing and developing Web sites and services that work across a diverse range of devices. From responsive Web design to future friendly thinking, here's how I've seen things evolve over the past year and a half.

If you haven't been keeping up with all the detailed conversations about multi-device Web design, I hope this overview and set of resources can quickly bring you up to speed. I'm only covering the last 18 months because it has been a very exciting time with lots of new ideas and voices. Prior to these developments, most multi-device Web design problems were solved with device detection and many still are. But the introduction of Responsive Web Design really stirred things up.

Responsive Web Design

Responsive Web Design is a combination of fluid grids and images with media queries to change layout based on the size of a device viewport. It uses feature detection (mostly on the client) to determine available screen capabilities and adapt accordingly. RWD is most useful for layout but some have extended it to interactive elements as well (although this often requires Javascript).

Responsive Web Design allows you to use a single URL structure for a site, thereby removing the need for separate mobile, tablet, desktop, etc. sites.

For a short overview read Ethan Marcotte's original article. For the full story read Ethan Marcotte's book. For a deeper dive into the philosophy behind RWD, read over Jeremy Keith's supporting arguments. To see a lot of responsive layout examples, browse around the mediaqueri.es site.

Challenges

Responsive Web Design isn't a silver bullet for mobile Web experiences. Not only does client-side adaptation require a careful approach, but it can also be difficult to optimize source order, media, third-party widgets, URL structure, and application design within a RWD solution.

Jason Grigsby has written up many of the reasons RWD doesn't instantly provide a mobile solution especially for images. I've documented (with concrete) examples why we opted for separate mobile and desktop templates in my last startup -a technique that's also employed by many Web companies like Facebook, Twitter, Google, etc. In short, separation tends to give greater ability to optimize specifically for mobile.

Mobile First Responsive Design

Mobile First Responsive Design takes Responsive Web Design and flips the process around to address some of the media query challenges outlined above. Instead of starting with a desktop site, you start with the mobile site and then progressively enhance to devices with larger screens.

The Yiibu team was one of the first to apply this approach and wrote about how they did it. Jason Grigsby has put together an overview and analysis of where Mobile First Responsive Design is being applied. Brad Frost has a more high-level write-up of the approach. For a more in-depth technical discussion, check out the thread about mobile-first media queries on the HMTL5 boilerplate project.

Techniques

Many folks are working through the challenges of designing Web sites for multiple devices. This includes detailed overviews of how to set up Mobile First Responsive Design markup, style sheet, and Javascript solutions.

Ethan Marcotte has shared what it takes for teams of developers and designers to collaborate on a responsive workflow based on lessons learned on the Boston Globe redesign. Scott Jehl outlined what Javascript is doing (PDF) behind the scenes of the Globe redesign (hint: a lot!).

Stephanie Rieger assembled a detailed overview (PDF) of a real-world mobile first responsive design solution for hundreds of devices. Stephan Hay put together a pragmatic overview of designing with media queries.

Media adaptation remains a big challenge for cross-device design. In particular, images, videos, data tables, fonts, and many other "widgets" need special care. Jason Grigsby has written up the situation with images and compiled many approaches for making images responsive. A number of solutions have also emerged for handling things like videos and data tables.

Server Side Components

Combining Mobile First Responsive Design with server side component (not full page) optimization is a way to extend client-side only solutions. With this technique, a single set of page templates define an entire Web site for all devices but key components within that site have device-class specific implementations that are rendered server side. Done right, this technique can deliver the best of both worlds without the challenges that can hamper each.

I've put together an overview of how a Responsive Design + Server Side Components structure can work with concrete examples. Bryan Rieger has outlined an extensive set of thoughts on server-side adaption techniques and Lyza Gardner has a complete overview of how all these techniques can work together. After analyzing many client-side solutions to dynamic images, Jason Grigsby outlined why using a server-side solution is probably the most future friendly.

Future Thinking

If all the considerations above seem like a lot to take in to create a Web site, they are. We are in a period of transition and still figuring things out. So expect to be learning and iterating a lot. That's both exciting and daunting.

It also prepares you for what's ahead. We've just begun to see the onset of cheap networked devices of every shape and size. The zombie apocalypse of devices is coming. And while we can't know exactly what the future will bring, we can strive to design and develop in a future-friendly way so we are better prepared for what's next.

Resources

I referenced lots of great multi-device Web design resources above. Here they are in one list. Read them in order and rock the future Web!

- Effective Design for Multiple Screen Sizesby Bryan Rieger

- Responsive Web Design (article) by Ethan Marcotte

- Responsive Web Design (book) by Ethan Marcotte

- There Is No Mobile Web by Jeremy Keith

- mediaqueri.es by various artisits

- CSS Media Query for Mobile is Fool’s Gold by Jason Grigsby

- Why Separate Mobile & Desktop Web Pages? by Luke Wroblewski

- About this site... by Yiibu

- Where are the Mobile First Responsive Web Designs? by Jason Grigsby

- Mobile-First Responsive Web Design by Brad Frost

- Mobile-first Media Queries by various artists

- The Responsive Designer’s Workflow by Ethan Marcotte

- Responsible & Responsive (PDF) by Scott Jehl

- Pragmatic Responsive Design (further details) by Stephanie Rieger

- A Closer Look at Media Queries by Stephen Hay

- Responsive IMGs — Part 1 by Jason Grigsby

- Responsive IMGs — Part 2 by Jason Grigsby

- Device detection as the future friendly img option by Jason Grigsby

- Responsive Video Embeds with FitVids by Dave Rupert

- Responsive Data Tables by Chris Coyier

- RESS: Responsive Design + Server Side Components by Luke Wroblewski

- Adaptation (PDF) by Bryan Rieger

- How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Set my Mobile Web Sites Free by Lyza Danger Gardner

- The Coming Zombie Apocalypse by Scott Jenson

- Future Friendly by various artists

Thursday, October 27. 2011

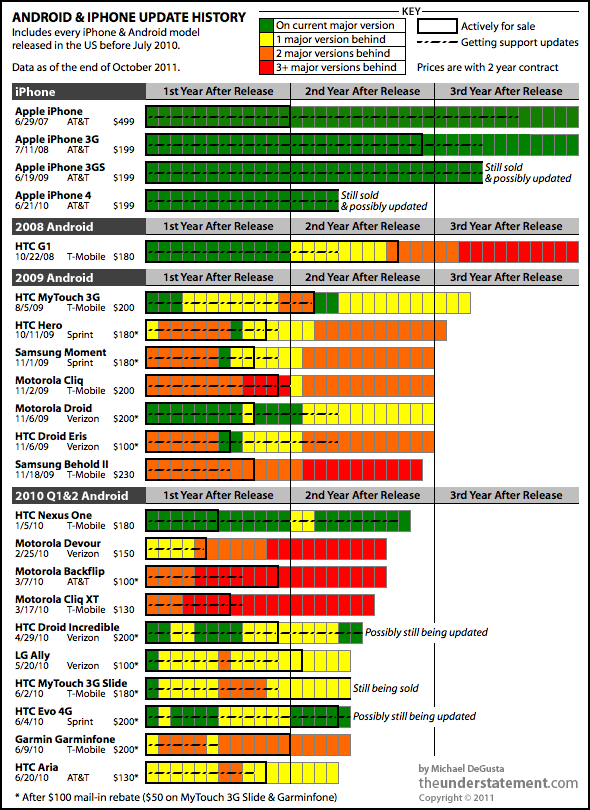

Android Orphans: Visualizing a Sad History of Support

-----

The announcement that Nexus One users won’t be getting upgraded to Android 4.0 Ice Cream Sandwich led some to justifiably question Google’s support of their devices. I look at it a little differently: Nexus One owners are lucky. I’ve been researching the history of OS updates on Android phones and Nexus One users have fared much, much better than most Android buyers.

I went back and found every Android phone shipped in the United States1 up through the middle of last year. I then tracked down every update that was released for each device - be it a major OS upgrade or a minor support patch - as well as prices and release & discontinuation dates. I compared these dates & versions to the currently shipping version of Android at the time. The resulting picture isn’t pretty - well, not for Android users:

Other than the original G1 and MyTouch, virtually all of the millions of phones represented by this chart are still under contract today. If you thought that entitled you to some support, think again:

- 7 of the 18 Android phones never ran a current version of the OS.

- 12 of 18 only ran a current version of the OS for a matter of weeks or less.

- 10 of 18 were at least two major versions behind well within their two year contract period.

- 11 of 18 stopped getting any support updates less than a year after release.

- 13 of 18 stopped getting any support updates before they even stopped selling the device or very shortly thereafter.

- 15 of 18 don’t run Gingerbread, which shipped in December 2010.

- In a few weeks, when Ice Cream Sandwich comes out, every device on here will be another major version behind.

- At least 16 of 18 will almost certainly never get Ice Cream Sandwich.

Also worth noting that each bar in the chart starts from the first day of release - so it only gets worse for people who bought their phone late in its sales period.

Why Is This So Bad?

This may be stating the obvious but there are at least three major reasons.

Consumers Get Screwed

Ever since the iPhone turned every smartphone into a blank slate, the value of a phone is largely derived from the software it can run and how well the phone can run it. When you’re making a 2 year commitment to a device, it’d be nice to have some way to tell if the software was going to be remotely current in a year or, heck, even a month. Turns out that’s nearly impossible - here are two examples:

The Samsung Behold II on T-Mobile was the most expensive Android phone ever and Samsung promoted that it would get a major update to Eclair at least. But at launch the phone was already two major versions behind — and then Samsung decided not to do the update after all, and it fell three major OS versions behind. Every one ever sold is still under contract today.

The Motorola Devour on Verizon launched with a Megan Fox Super Bowl ad, while reviews said it was “built to last and it delivers on features.” As it turned out, the Devour shipped with an OS that was already outdated. Before the next Super Bowl came around, it was three major versions behind. Every one ever sold is still under contract until sometime next year.

Developers Are Constrained

Besides the obvious platform fragmentation problems, consider this comparison: iOS developers, like Instapaper’s Marco Arment, waited patiently until just this month to raise their apps’ minimum requirement to the 11 month old iOS 4.2.1. They can do so knowing that it’s been well over 3 years since anyone bought an iPhone that couldn’t run that OS. If developers apply that same standard to Android, it will be at least 2015 before they can start requiring 2010’s Gingerbread OS. That’s because every US carrier is still selling - even just now introducing2 - smartphones that will almost certainly never run Gingerbread and beyond. Further, those are phones still selling for actual upfront money - I’m not even counting the generally even more outdated & presumably much more popular free phones.

It seems this is one area the Android/Windows comparison holds up: most app developers will end up targeting an ancient version of the OS in order to maximize market reach.

Security Risks Loom

In the chart, the dashed line in the middle of each bar indicates how long that phone was getting any kind of support updates - not just major OS upgrades. The significant majority of models have received very limited support after sales were discontinued. If a security or privacy problem popped up in old versions of Android or its associated apps (i.e. the browser), it’s hard to imagine that all of these no-longer-supported phones would be updated. This is only less likely as the number of phones that manufacturers would have to go back and deal with increases: Motorola, Samsung, and HTC all have at least 20 models each in the field already, each with a range of carriers that seemingly have to be dealt with individually.

Why Don’t Android Phones Get Updated?

That’s a very good question. Obviously a big part of the problem is that Android has to go from Google to the phone manufacturers to the carriers to the devices, whereas iOS just goes from Apple directly to devices. The hacker community (e.g. CyanogenMod, et cetera) has frequently managed to get these phones to run the newer operating systems, so it isn’t a hardware issue.

It appears to be a widely held viewpoint3 that there’s no incentive for smartphone manufacturers to update the OS: because manufacturers don’t make any money after the hardware sale, they want you to buy another phone as soon as possible. If that’s really the case, the phone manufacturers are spectacularly dumb: ignoring the 2 year contract cycle & abandoning your users isn’t going to engender much loyalty when they do buy a new phone. Further, it’s been fairly well established that Apple also really only makes money from hardware sales, and yet their long term update support is excellent (see chart).

In other words, Apple’s way of getting you to buy a new phone is to make you really happy with your current one, whereas apparently Android phone makers think they can get you to buy a new phone by making you really unhappy with your current one. Then again, all of this may be ascribing motives and intent where none exist - it’s entirely possible that the root cause of the problem is just flat-out bad management (and/or the aforementioned spectacular dumbness).

A Price Observation

All of the even slightly cheaper phones are much worse than the iPhone when it comes to OS support, but it’s interesting to note that most of the phones on this list were actually not cheaper than the iPhone when they were released. Unlike the iPhone however, the “full-priced” phones are frequently discounted in subsequent months. So the “low cost” phones that fueled Android’s generally accepted price advantage in this period were basically either (a) cheaper from the outset, and ergo likely outdated & terribly supported or (b) purchased later in the phone’s lifecycle, and ergo likely outdated & terribly supported.

Also, at any price point you’d better love your rebates. If you’re financially constrained enough to be driven by upfront price, you can’t be that excited about plunking down another $100 cash and waiting weeks or more to get it back. And sometimes all you’re getting back is a “$100 Promotion Card” for your chosen provider. Needless to say, the iPhone has never had a rebate.

Along similar lines, a very small but perhaps telling point: the price of every single Android phone I looked at ended with 99 cents - something Apple has never done (the iPhone is $199, not $199.99). It’s almost like a warning sign: you’re buying a platform that will nickel-and-dime you with ads and undeletable bloatware, and it starts with those 99 cents. And that damn rebate form they’re hoping you don’t send in.

Notes on the chart and data

Why stop at June 2010?

I’m not going to. I do think that having 15 months or so of history gives a good perspective on how a phone has been treated, but it’s also just a labor issue - it takes a while to dredge through the various sites to determine the history of each device. I plan to continue on and might also try to publish the underlying table with references. I also acknowledge that it’s possible I’ve missed something along the way.

Android Release Dates

For the major Android version release dates, I used the date at which it was actually available on a normal phone you could get via normal means. I did not use the earlier SDK release date, nor the date at which ROMs, hacks, source, et cetera were available.

Outside the US

Finally, it’s worth noting that people outside the US have often had it even worse. For example, the Nexus One didn’t go on sale in Europe until 5 months after the US, the Droid/Milestone FroYo update happened over 7 months later there, and the Cliq never got updated at all outside of the US.

-

Thanks primarily to CNET & Wikipedia for the list of phones.?

-

Yes, AT&T committed to Gingerbread updates for its 2011 Android phones, but only those that had already been released at the time of the July 25 press release. The Impulse doesn’t meet that criterion. Nor does the Sharp FX Plus.?

-

A couple of samples just from the past week: 1, 2 - in comments.?

Thursday, October 20. 2011

Before Netscape: the forgotten Web browsers of the early 1990s

When Tim Berners-Lee arrived at CERN, Geneva's celebrated European Particle Physics Laboratory in 1980, the enterprise had hired him to upgrade the control systems for several of the lab's particle accelerators. But almost immediately, the inventor of the modern webpage noticed a problem: thousands of people were floating in and out of the famous research institute, many of them temporary hires.

"The big challenge for contract programmers was to try to understand the systems, both human and computer, that ran this fantastic playground," Berners-Lee later wrote. "Much of the crucial information existed only in people's heads."

So in his spare time, he wrote up some software to address this shortfall: a little program he named Enquire. It allowed users to create "nodes"—information-packed index card-style pages that linked to other pages. Unfortunately, the PASCAL application ran on CERN's proprietary operating system. "The few people who saw it thought it was a nice idea, but no one used it. Eventually, the disk was lost, and with it, the original Enquire."

Some years later Berners-Lee returned to CERN. This time he relaunched his "World Wide Web" project in a way that would more likely secure its success. On August 6, 1991, he published an explanation of WWW on the alt.hypertext usegroup. He also released a code library, libWWW, which he wrote with his assistant Jean-François Groff. The library allowed participants to create their own Web browsers.

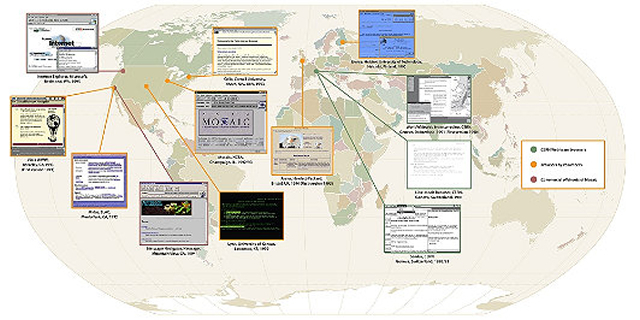

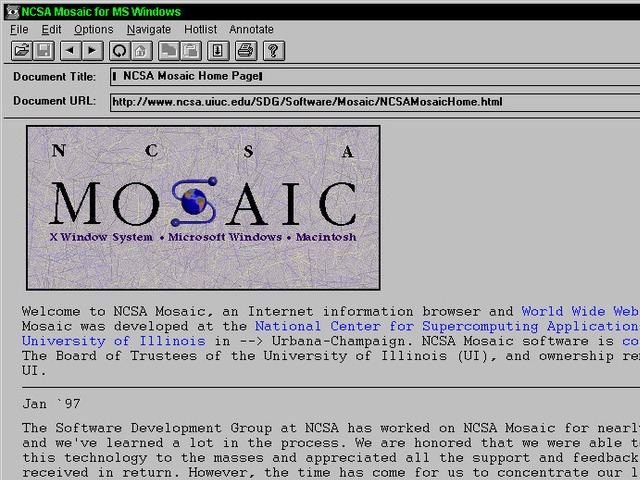

"Their efforts—over half a dozen browsers within 18 months—saved the poorly funded Web project and kicked off the Web development community," notes a commemoration of this project by the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. The best known early browser was Mosaic, produced by Marc Andreesen and Eric Bina at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA).

Mosaic was soon spun into Netscape, but it was not the first browser. A map assembled by the Museum offers a sense of the global scope of the early project. What's striking about these early applications is that they had already worked out many of the features we associate with later browsers. Here is a tour of World Wide Web viewing applications, before they became famous.

The CERN browsers

Tim Berners-Lee's original 1990 WorldWideWeb browser was both a browser and an editor. That was the direction he hoped future browser projects would go. CERN has put together a reproduction of its formative content. As you can see in the screenshot below, by 1993 it offered many of the characteristics of modern browsers.

The software's biggest limitation was that it ran on the NeXTStep operating system. But shortly after WorldWideWeb, CERN mathematics intern Nicola Pellow wrote a line mode browser that could function elsewhere, including on UNIX and MS-DOS networks. Thus "anyone could access the web," explains Internet historian Bill Stewart, "at that point consisting primarily of the CERN phone book."

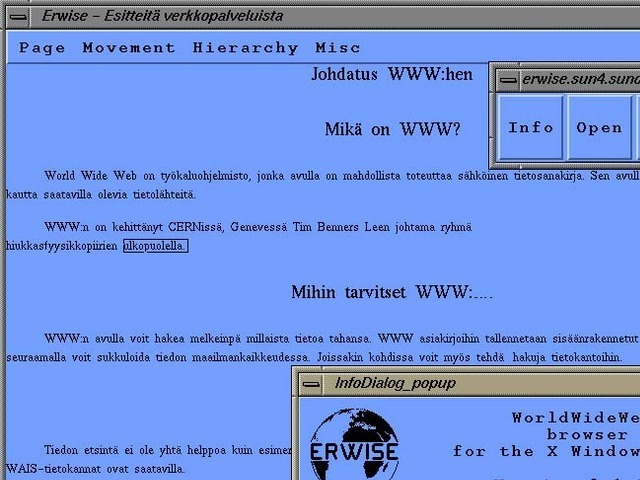

Erwise

Erwise came next. It was written by four Finnish college students in 1991 and released in 1992. Erwise is credited as the first browser that offered a graphical interface. It could also search for words on pages.

Berners-Lee wrote a review of Erwise in 1992. He noted its ability to handle various fonts, underline hyperlinks, let users double-click them to jump to other pages, and to host multiple windows.

"Erwise looks very smart," he declared, albeit puzzling over a "strange box which is around one word in the document, a little like a selection box or a button. It is neither of these—perhaps a handle for something to come."

So why didn't the application take off? In a later interview, one of Erwise's creators noted that Finland was mired in a deep recession at the time. The country was devoid of angel investors.

"We could not have created a business around Erwise in Finland then," he explained. "The only way we could have made money would have been to continue our developing it so that Netscape might have finally bought us. Still, the big thing is, we could have reached the initial Mosaic level with relatively small extra work. We should have just finalized Erwise and published it on several platforms."

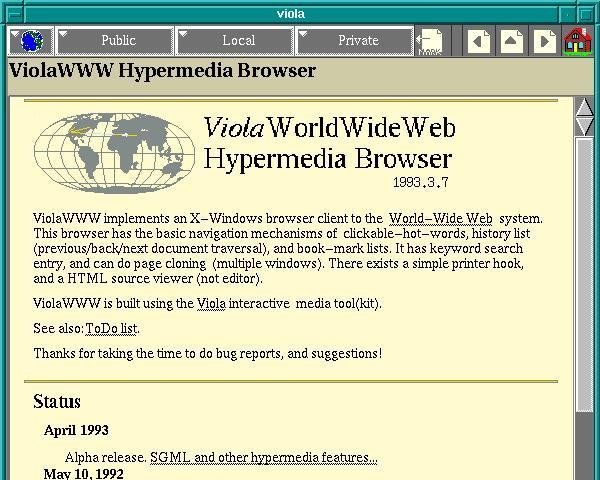

ViolaWWW

ViolaWWW was released in April of 1992. Developer Pei-Yuan Wei wrote it at the University of California at Berkeley via his UNIX-based Viola programming/scripting language. No, Pei Wei didn't play the viola, "it just happened to make a snappy abbreviation" of Visually Interactive Object-oriented Language and Application, write James Gillies and Robert Cailliau in their history of the World Wide Web.

Wei appears to have gotten his inspiration from the early Mac program HyperCard, which allowed users to build matrices of formatted hyper-linked documents. "HyperCard was very compelling back then, you know graphically, this hyperlink thing," he later recalled. But the program was "not very global and it only worked on Mac. And I didn't even have a Mac."

But he did have access to UNIX X-terminals at UC Berkeley's Experimental Computing Facility. "I got a HyperCard manual and looked at it and just basically took the concepts and implemented them in X-windows." Except, most impressively, he created them via his Viola language.

One of the most significant and innovative features of ViolaWWW was that it allowed a developer to embed scripts and "applets" in the browser page. This anticipated the huge wave of Java-based applet features that appeared on websites in the later 1990s.

In his documentation, Wei also noted various "misfeatures" of ViolaWWW, most notably its inaccessibility to PCs.

- Not ported to PC platform.

- HTML Printing is not supported.

- HTTP is not interruptable, and not multi-threaded.

- Proxy is still not supported.

- Language interpreter is not multi-threaded.

"The author is working on these problems... etc," Wei acknowledged at the time. Still, "a very neat browser useable by anyone: very intuitive and straightforward," Berners-Lee concluded in his review of ViolaWWW. "The extra features are probably more than 90% of 'real' users will actually use, but just the things which an experienced user will want."

Midas and Samba

In September of 1991, Stanford Linear Accelerator physicist Paul Kunz visited CERN. He returned with the code necessary to set up the first North American Web server at SLAC. "I've just been to CERN," Kunz told SLAC's head librarian Louise Addis, "and I found this wonderful thing that a guy named Tim Berners-Lee is developing. It's just the ticket for what you guys need for your database."

Addis agreed. The site's head librarian put the research center's key database over the Web. Fermilab physicists set up a server shortly after.

Then over the summer of 1992 SLAC physicist Tony Johnson wrote Midas, a graphical browser for the Stanford physics community. The big draw for Midas users was that it could display postscript documents, favored by physicists because of their ability to accurately reproduce paper-scribbled scientific formulas.

"With these key advances, Web use surged in the high energy physics community," concluded a 2001 Department of Energy assessment of SLAC's progress.

Meanwhile, CERN associates Pellow and Robert Cailliau released the first Web browser for the Macintosh computer. Gillies and Cailliau narrate Samba's development.

For Pellow, progress in getting Samba up and running was slow, because after every few links it would crash and nobody could work out why. "The Mac browser was still in a buggy form,' lamented Tim [Berners-Lee] in a September '92 newsletter. 'A W3 T-shirt to the first one to bring it up and running!" he announced. The T shirt duly went to Fermilab's John Streets, who tracked down the bug, allowing Nicola Pellow to get on with producing a usable version of Samba.

Samba "was an attempt to port the design of the original WWW browser, which I wrote on the NeXT machine, onto the Mac platform," Berners-Lee adds, "but was not ready before NCSA [National Center for Supercomputing Applications] brought out the Mac version of Mosaic, which eclipsed it."

Mosaic

Mosaic was "the spark that lit the Web's explosive growth in 1993," historians Gillies and Cailliau explain. But it could not have been developed without forerunners and the NCSA's University of Illinois offices, which were equipped with the best UNIX machines. NCSA also had Dr. Ping Fu, a PhD computer graphics wizard who had worked on morphing effects for Terminator 2. She had recently hired an assistant named Marc Andreesen.

"How about you write a graphical interface for a browser?" Fu suggested to her new helper. "What's a browser?" Andreesen asked. But several days later NCSA staff member Dave Thompson gave a demonstration of Nicola Pellow's early line browser and Pei Wei's ViolaWWW. And just before this demo, Tony Johnson posted the first public release of Midas.

The latter software set Andreesen back on his heels. "Superb! Fantastic! Stunning! Impressive as hell!" he wrote to Johnson. Then Andreesen got NCSA Unix expert Eric Bina to help him write their own X-browser.

Mosaic offered many new web features, including support for video clips, sound, forms, bookmarks, and history files. "The striking thing about it was that unlike all the earlier X-browsers, it was all contained in a single file," Gillies and Cailliau explain:

Installing it was as simple as pulling it across the network and running it. Later on Mosaic would rise to fame because of the <IMG> tag that allowed you to put images inline for the first time, rather than having them pop up in a different window like Tim's original NeXT browser did. That made it easier for people to make Web pages look more like the familiar print media they were use to; not everyone's idea of a brave new world, but it certainly got Mosaic noticed.

"What I think Marc did really well," Tim Berners-Lee later wrote, "is make it very easy to install, and he supported it by fixing bugs via e-mail any time night or day. You'd send him a bug report and then two hours later he'd mail you a fix."

Perhaps Mosaic's biggest breakthrough, in retrospect, was that it was a cross-platform browser. "By the power vested in me by nobody in particular, X-Mosaic is hereby released," Andreeson proudly declared on the www-talk group on January 23, 1993. Aleks Totic unveiled his Mac version a few months later. A PC version came from the hands of Chris Wilson and Jon Mittelhauser.

The Mosaic browser was based on Viola and Midas, the Computer History museum's exhibit notes. And it used the CERN code library. "But unlike others, it was reliable, could be installed by amateurs, and soon added colorful graphics within Web pages instead of as separate windows."

A guy from Japan

But Mosaic wasn't the only innovation to show up on the scene around that same time. University of Kansas student Lou Montulli adapted a campus information hypertext browser for the Internet and Web. It launched in March, 1993. "Lynx quickly became the preferred web browser for character mode terminals without graphics, and remains in use today," historian Stewart explains.

And at Cornell University's Law School, Tom Bruce was writing a Web application for PCs, "since those were the computers that lawyers tended to use," Gillies and Cailliau observe. Bruce unveiled his browser Cello on June 8, 1993, "which was soon being downloaded at a rate of 500 copies a day."

Six months later, Andreesen was in Mountain View, California, his team poised to release Mosaic Netscape on October 13, 1994. He, Totic, and Mittelhauser nervously put the application up on an FTP server. The latter developer later recalled the moment. "And it was five minutes and we're sitting there. Nothing has happened. And all of a sudden the first download happened. It was a guy from Japan. We swore we'd send him a T shirt!"

But what this complex story reminds is that is that no innovation is created by one person. The Web browser was propelled into our lives by visionaries around the world, people who often didn't quite understand what they were doing, but were motivated by curiosity, practical concerns, or even playfulness. Their separate sparks of genius kept the process going. So did Tim Berners-Lee's insistence that the project stay collaborative and, most importantly, open.

"The early days of the web were very hand-to-mouth," he writes. "So many things to do, such a delicate flame to keep alive."

Further reading

- Tim Berners-Lee, Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web

- James Gillies and R. Cailliau, How the web was born

- Bill Stewart, Living Internet (www.livinginternet.com)

Wednesday, October 19. 2011

Neuromancing the Cloud: How Siri Could Lead to Real Artificial Intelligence

Via Forbes

By E.D. Kain

-----

Outside of its remarkable sales, the real star of the iPhone 4S show has been Siri, Apple’s new voice recognition software. The intuitive voice recognition software is the closest to A.I. we’ve seen on a smartphone to date.

Over the weekend I noted that Siri has some resemblance to the IBM supercomputer, Watson, and speculated that someday Watson would be in our pockets while the supercomputers of the future might look a lot more like the Artificial Intelligence we’ve read about in science fiction novels today, such as the mysterious Wintermute from William Gibson’s Neuromancer.

Over at Wired, John Stokes explains how Siri and the Apple cloud could lead to the advent of a real Artificial Intelligence:

In the traditional world of canned, chatterbot-style “AI,” users had to wait for a software update to get access to new input/output pairs. But since Siri is a cloud application, Apple’s engineers can continuously keep adding these hard-coded input/output pairs to it. Every time an Apple engineer thinks of a clever response for Siri to give to a particular bit of input, that engineer can insert the new pair into Siri’s repertoire instantaneously, so that the very next instant every one of the service’s millions of users will have access to it. Apple engineers can also take a look at the kinds of queries that are popular with Siri users at any given moment, and add canned responses based on what’s trending.

In this way, we can expect Siri’s repertoire of clever comebacks to grow in real-time through the collective effort of hundreds of Apple employees and tens or hundreds of millions of users, until it reaches the point where an adult user will be able to carry out a multipart exchange with the bot that, for all intents and purposes, looks like an intelligent conversation.

Meanwhile, the technology undergirding the software and iPhone hardware will continue to improve. Now, this may not be the AI we had in mind, but it also probably won’t be the final word in Artificial Intelligence either. Other companies, such as IBM, are working to develop other ‘cognitive computers‘ as well.

And while the Singularity may indeed be far, far away, it’s still exciting to see how some forms of A.I. may emerge at least in part through cloud-sourcing.

Tuesday, October 18. 2011

The developer's guide to browser adoption rates

Via netmagazine

-----

As new platform versions get released more and more quickly, are users keeping up? Zeh Fernando, a senior developer at Firstborn, looks at current adoption rates and points to some intriguing trends

There's a quiet revolution happening on the web, and it's related to one aspect of the rich web that is rarely discussed: the adoption rate of new platform versions.

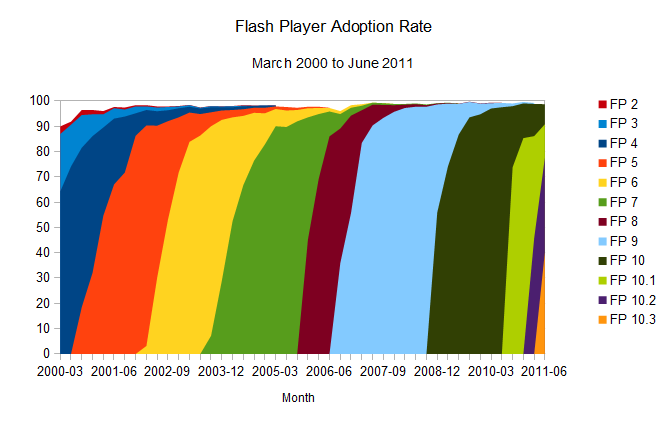

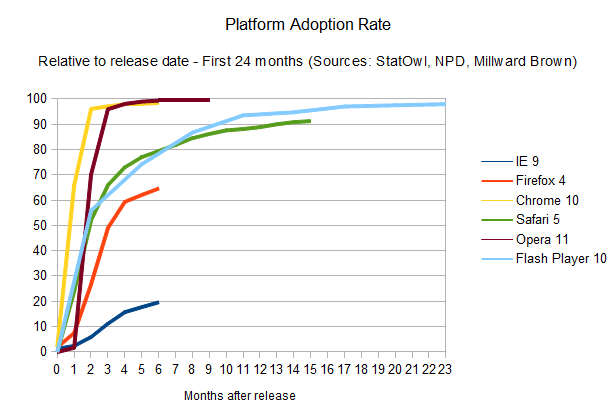

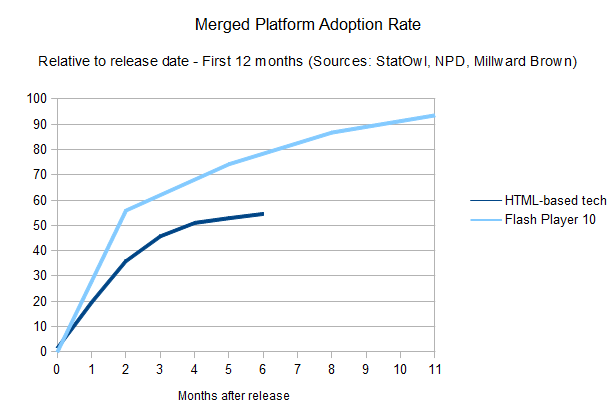

First, to put things into perspective, we can look at the most popular browser plug-in out there: Adobe's Flash Player. It's pretty well known that the adoption of new versions of the Flash plug-in happens pretty quickly: users update Flash Player quickly and often after a new version of the plug-in is released [see Adobe's sponsored NPD, United States, Mar 2000-Jun 2006, and Milward Brown’s “Mature markets”, Sep 2006-Jun 2011 research (here and here) collected by way of the Internet Archive and saved over time; here’s the complete spreadsheet with version release date help from Wikipedia].

To simplify it: give it around eight months, and 90 per cent of the desktops out there will have the newest version of the plug-in installed. And as the numbers represented in the charts above show, this update rate is only improving. That’s party due to the fact that Chrome, now a powerful force in the browser battles, installs new versions of the Flash Player automatically (sometimes even before it is formally released by Adobe), and that Firefox frequently detects the user's version and insists on them installing an updated, more secure version.

Gone are the days where the Flash platform needed an event such as the Olympics or a major website like MySpace or YouTube making use of a new version of Flash to make it propagate faster; this now happens naturally. Version 10.3 only needed one month to get to a 40.5 per cent install base, and given the trends set by the previous releases, it's likely that the plug-in's new version 11 will break new speed records.

Any technology that can allow developers and publishers to take advantage of it in a real world scenario so fast has to be considered a breakthrough. Any new platform feature can be proposed, developed, and made available with cross-platform consistency in record time; such is the advantage of a proprietary platform like Flash. To mention one of the more adequate examples of the opposite effect, features added to the HTML platform (in any of its flavours or versions) can take many years of proposal and beta support until they're officially accepted, and when that happens, it takes many more years until it becomes available on most of the computers out there. A plug-in is usually easier and quicker to update than a browser too.

That has been the story so far. But that's changing.

Advertisement

Google Chrome adoption rate

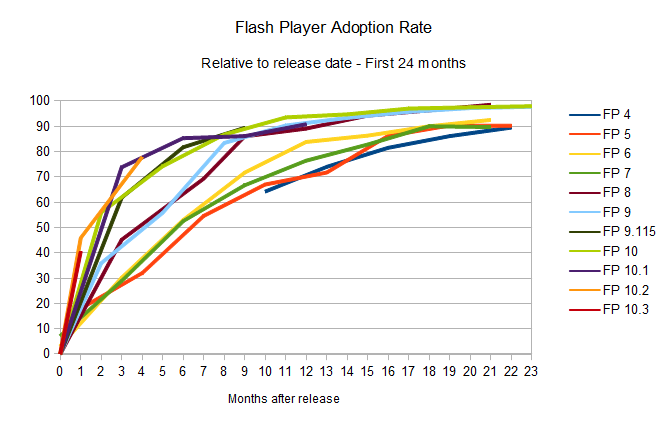

Looking at the statistics for the adoption rate of the Flash plug-in, it's easy to see it's accelerating constantly, meaning the last versions of the player were finding their way to the user's desktops quicker and quicker with every new version. But when you have a look at similar adoption rate for browsers, a somewhat similar but more complex story unfolds.

Let's have a look at Google Chrome's adoption rates in the same manner I've done the Flash player comparisons, to see how many people had each of its version installed (but notice that, given that Chrome is not used by 100 per cent of the people on the internet, it is normalised for the comparison to make sense).

The striking thing here is that the adoption rate of Google Chrome manages to be faster than Flash Player itself [see StatOwl's web browser usage statistics, browser version release dates from Google Chrome on Wikipedia]. This is helped, of course, by the fact that updates happens automatically (without user approval necessary) and easily (using its smart diff-based update engine to provide small update files). As a result, Chrome can get to the same 90 per cent of user penetration rate in around two months only; but what it really means is that Google manages to put out updates to their HTML engine much faster than Flash Player.

Of course, there's a catch here if we're to compare that to Flash Player adoption rate: as mentioned, Google does the same auto-update for the Flash Player itself. So the point is not that there's a race and Chrome's HTML engine is leading it; instead, Chrome is changing the rules of the game to not only make everybody win, but to make them win faster.

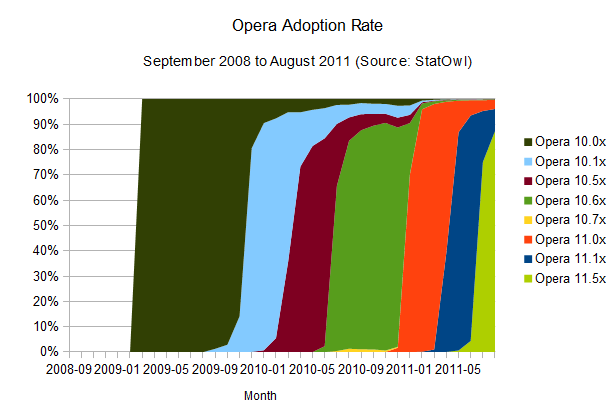

Opera adoption rate

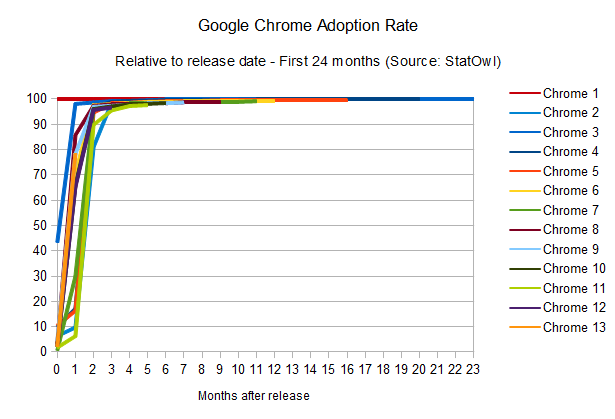

The fast update rate employed by Chrome is not news. In fact, one smaller player on the browser front, Opera, tells a similar story.

Opera also manages to have updates reach a larger audience very quickly [see browser version release dates from History of the Opera web browser, Opera 10 and Opera 11 on Wikipedia]. This is probably due to its automatic update feature. The mass updates seem to take a little bit longer than Chrome, around three months for a 90 per cent reach, but it's important to notice that its update workflow is not entirely automatic; last time I tested, it still required user approval (and Admin rights) to work its magic.

Firefox adoption rate

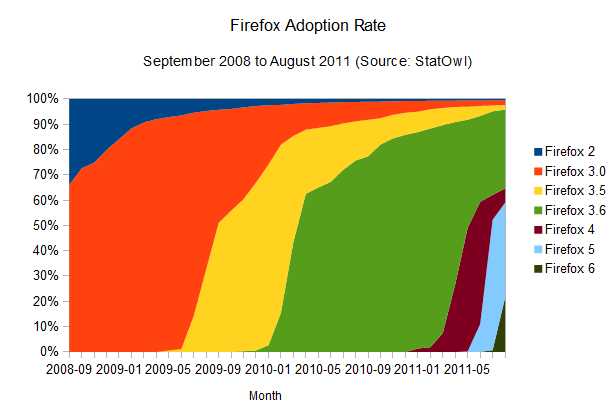

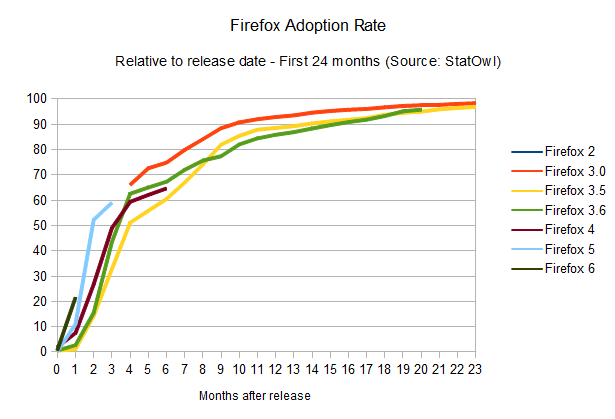

The results of this browser update analysis start deviating when we take a similar look at the adoption rates of the other browsers. Take Firefox, for example:

It's also clear that Firefox's update rate is accelerating (browser version release dates from Firefox on Wikipedia), and the time-to-90-per-cent is shrinking: it should take around 12 months to get to that point. And given Mozilla's decision to adopt release cycles that mimics Chrome's, with its quick release schedule, and automatic updates, we're likely to see a big boost in those numbers, potentially making the update adoption rates as good as Chrome's.

One interesting point here is that a few users seem to have been stuck with Firefox 3.6, which is the last version that employs the old updating method (where the user has to manually check for new versions), causing Firefox updates to spread quickly but stall around the 60 per cent mark. Some users still need to realise there's an update waiting for them; and similarly to the problem the Mozilla team had to face with Firefox 3.5, it's likely that we'll see the update being automatically imposed upon users soon, although they'll still be able to disable it. It's gonna be interesting to see how this develops over the next few months.

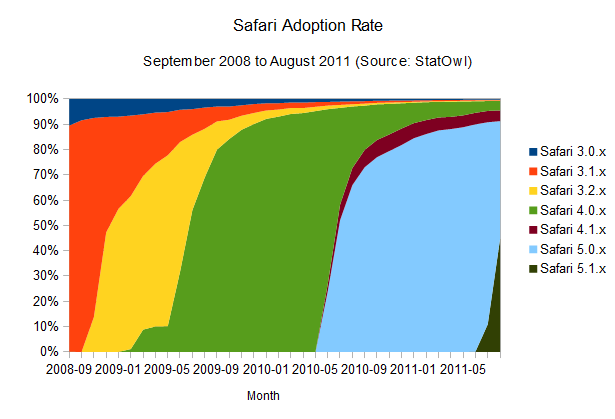

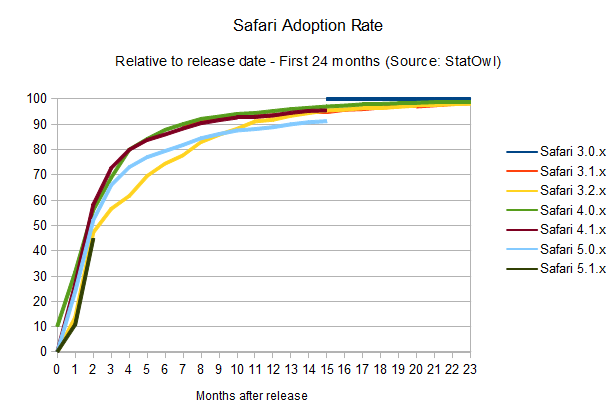

What does Apple's Safari look like?

Safari adoption rate

Right now, adoption rates seem on par with Firefox (browser version release dates from Safari on Wikipedia), maybe a bit better, since it takes users around 10 months to get a 90 per cent adoption rate of the newest versions of the browser. The interesting thing is that this seems to happen in a pretty solid fashion, probably helped by Apple's OS X frequent update schedule, since the browser update is bundled with system updates. Overall, update rates are not improving – but they're keeping at a good pace.

Notice that the small bump on the above charts for Safari 4.0.x is due to the public beta release of that version of the browser, and the odd area for Safari 4.1.x is due to its release in pair with Safari 5.0.x, but for a different version of OSX.

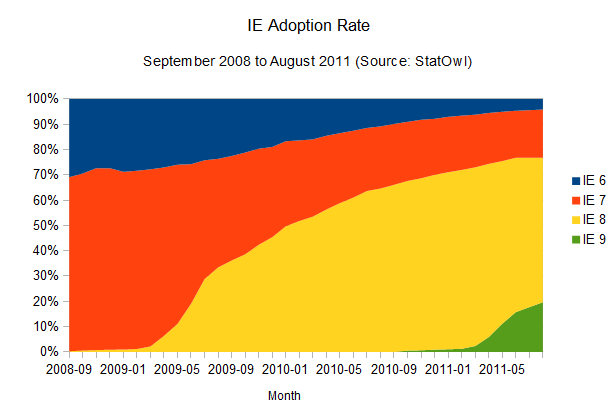

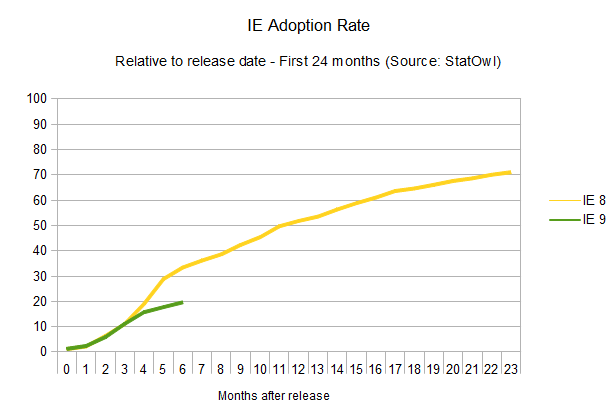

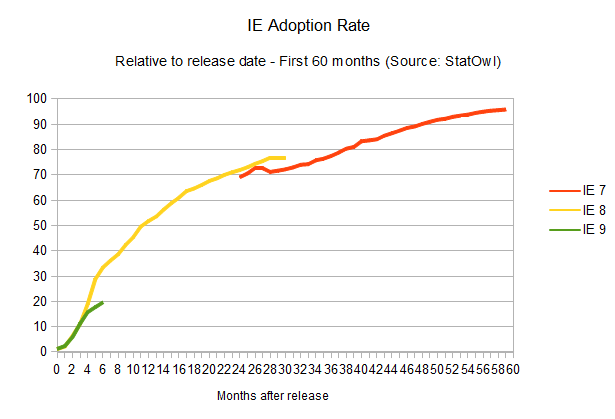

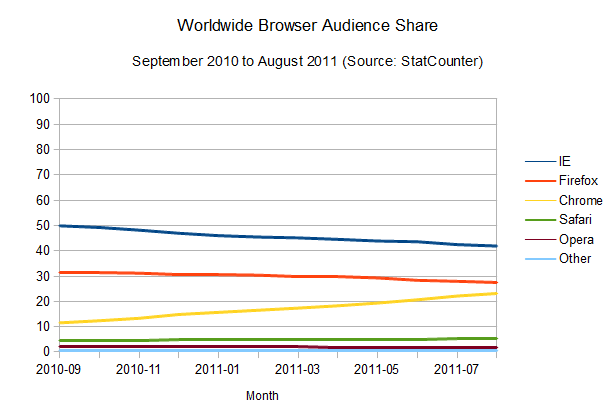

IE adoption rate

All in all it seems to me that browser vendors, as well as the users, are starting to get it. Overall, updates are happening faster and the cycle from interesting idea to a feature that can be used on a real-world scenario is getting shorter and shorter.

There's just one big asterisk in this prognosis: the adoption rate for the most popular browser out there.

The adoption rate of updates to Internet Explorer is not improving at all (browser version release dates from Internet Explorer on Wikipedia). In fact, it seems to be getting worse.

As is historically known, the adoption rate of new versions of Internet Explorer is, well, painstakingly slow. IE6, a browser that was released 10 years ago, is still used by four per cent of the IE users, and newer versions don't fare much better. IE7, released five years ago, is still used by 19 per cent of all the IE users. The renewing cycle here is so slow that it's impossible to even try to guess how long it would take for new versions to reach a 90 per cent adoption rate, given the lack of reliable data. But considering update rates haven't improved at all for new versions of the browser (in fact, IE9 is doing worse than IE8 in terms of adoption), one can assume a cycle of four years until any released version of Internet Explorer reaches 90 per cent user adoption. Microsoft itself is trying to make users abandon IE6, and whatever the reason for the version lag – system administrators hung up on old versions, proliferation of pirated XP installations that can't update – it's just not getting there.

And the adoption rates of new HTML features is, unfortunately, only as quick as the adoption rate of the slowest browser, especially when it's someone that still powers such a large number of desktops out there.

Internet Explorer will probably continue to be the most popular browser for a very long time.

The long road for HTML-based tech

The story, so far, has been that browser plug-ins are usually easier and quicker to update. Developers can rely on new features of a proprietary platform such as Flash earlier than someone who uses the native HTML platform could. This is changing, however, one browser at a time.

A merged chart, using the weighted distribution of each browser's penetration and the time it takes for its users to update, tells that the overall story for HTML developers still has a long way to go.

Of course, this shouldn't be taken into account blindly. You should always have your audience in mind when developing a website, and come up with your own numbers when deciding what kind of features to make use of. But it works as a general rule of thumb to be taken into account before falling in love with whatever feature has just been added to a browser's rendering engine (or a new plug-in version, for that matter). In that sense, be sure to use websites like caniuse.com to check on what's supported (check the “global user stats” box!), and look at whatever browser share data you have for your audience (and desktop/mobile share too, although it's out of the scope of this article).

Conclusion

Updating the browser has always been a certain roadblock to most users. In the past, even maintaining bookmarks and preferences when doing an update was a problem.

That has already changed. With the exception of Internet Explorer, browsers vendors are realising how important it is to provide easy and timely updates for users; similarly, users themselves are, I like to believe, starting to realise how an update can be easy and painless too.

Personally, I used to look at the penetration numbers of Flash and HTML in comparison to each other and it always baffled me how anyone would compare them in a realistic fashion when it came down to the speed that any new feature would take to be adopted globally. Looking at them this time, however, gave me a different view on things; our rich web platforms are not only getting better, but they're getting better at getting better, by doing so faster.

In retrospect, it seems obvious now, but I can only see all other browser vendors adopting similar quick-release, auto-update features similar to what was introduced by Chrome. Safari probably needs to make the updates install without user intervention, and we can only hope that Microsoft will consider something similar for Internet Explorer. And when that happens, the web, both HTML-based and plug-ins-based but especially on the HTML side, will be moving at a pace that we haven't seen before. And everybody wins with that.

Monday, October 17. 2011

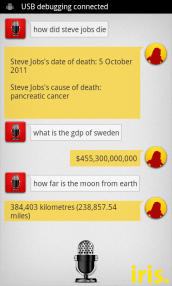

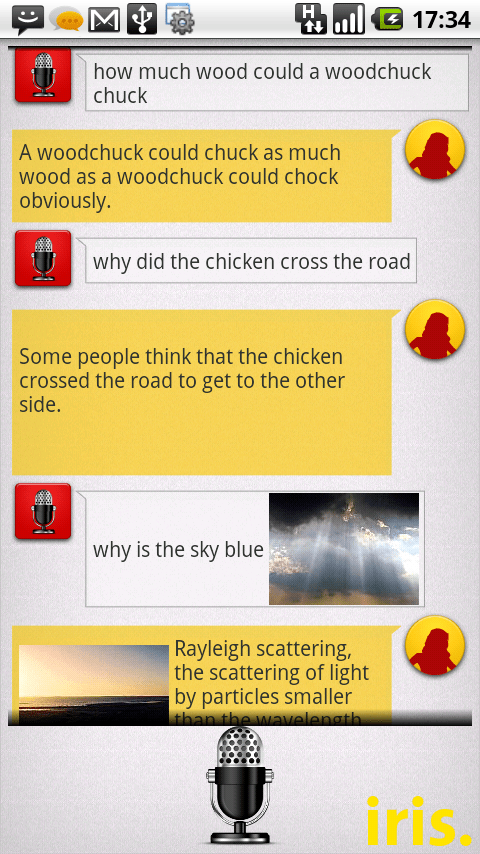

Iris Is (Sort Of) Siri For Android

While voice control has been part of Android since the dawn of time, Siri came along and ruined the fun with its superior search and understanding capabilities. However, an industrious team of folks from Dexetra.com, led by Narayan Babu, built a Siri-alike in just 8 hours during a hackathon.

Iris allows you to search on various subjects including conversions, art, literature, history, and biology. You can ask it “What is a fish?” and it will reply with a paragraph from Wikipedia focusing on our finned friends.

The app will soon be available soon from the Android Marketplace but I

tried it recently and found it a bit sparse but quite cool. It uses

Android’s speech-to-text functions to understand basic questions and

Narayan and his buddies are improving the app all the time.

The coolest thing? The finished the app in eight hours.

When we started seeing results, everyone got excited and started a high speed coding race. In no time, we added Voice input, Text-to-speech, also a lot of hueristic humor into Iris. Not until late evening we decided on the name “iris.”, which would be Siri in reverse. And we also reverse engineered a crazy expansion – Intelligent Rival Imitator of Siri. We were still in the fun mode, but when we started using it the results were actually good, really good.

You can grab the early, early beta APK here but I recommend waiting for the official version to arrive this week. It just goes to show you that amazing things can pop up everywhere.

Wednesday, October 12. 2011

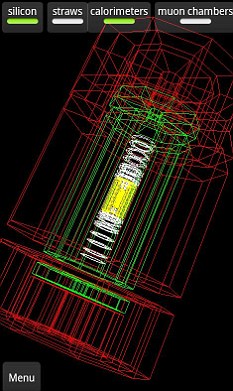

Android app puts 3D Large Hadron Collider in your hand

Via DailyMail

-----

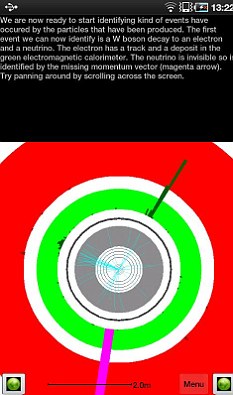

The app allows you to 'build' a 3D view of the reactions inside the LHC, and the huge banks of detectors surrounding the chamber, layer by layer. It's a spectacular insight into the machines at CERN

The new LHSEE app, free on Google Android phones and tablets, lets users see events unfolding live inside the particle accelerator in a 3D view. You can even see individual protons colliding.

The app has already been downloaded more than 10,000 times.

It was created by scientists at Oxford University, and has the full approval of CERN.

Naturally, it can't capture everything - the LHC produces gigabytes of data every second - but the view offers an exhilarating insight into 'Big Science'.

Tutorial videos about the ATLAS detector provide a relatively easy 'way in', and the 3D views allow you to view a stripped down version, then add layers of detectors.

It gives a very immediate, physical sense of the reactions going on inside - you can rotate the 3D model to view reactions from any angle.

It is pitched, according to Android market, at 'experts and non-experts alike', and offers the chance to explore different parts of the detector and learn about the reactions it's looking for.

Be warned, though - despite a game entitled 'Hunt the Higgs', it isn't exactly Angry Birds. You have to comb slides of reactions, guessing which subatomic particles are involved.

The app was built a team headed by Oxford University physicist Dr Alan Barr.'For ages I’d been thinking that with the amazing capabilities on modern smartphones we really ought to be able to make a really great app - something that would allow everybody to access the LHC data,' said Barr on the official Oxford science blog.

The app initially looks intimidating, but if you persist, the tutorial modes give a fairly gentle 'learning curve' towards understanding how the detectors surrounding the LHC work, and what they are looking for

'I’d sounded out a few commercial companies who said they could do the job but I found that it would be expensive, and of course I’d have to teach their designers a lot of physics. So the idea was shelved.'

'Then, a few months later, I had one of those eureka moments that make Oxford so wonderful.

'I was having a cuppa in the physics common room, and happened to overhear a conversation from Chris Boddy, one of our very many bright Oxford physics graduate students.'

'He was telling his friends that for fun he was writing some small test games for his Android phone. Well you just can’t let moments like that pass.'

By leading users through the coloured slides produced by the LHC, the app 'reverse engineers' the imagery so home users can understand the reactions - eventually. With the LHC predicted to either find the Higgs Boson or prove its non-existence next year, the capacity to watch events 'live' should also prove popular.

'With the app you can understand what these strange shapes and lines actually mean - in terms of the individual particles detected. Our hope is that people can now appreciate the pictures and the science all the more - and perhaps even be a little inspired,' said Barr.

As yet, the team has announced no plans for an iPhone version.

Saturday, October 08. 2011

Computer Virus Hits U.S. Drone Fleet

Photo courtesy of Bryan William Jones

A computer virus has infected the cockpits of America’s Predator and Reaper drones, logging pilots’ every keystroke as they remotely fly missions over Afghanistan and other warzones.

The virus, first detected nearly two weeks ago by the military’s Host-Based Security System, has not prevented pilots at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada from flying their missions overseas. Nor have there been any confirmed incidents of classified information being lost or sent to an outside source. But the virus has resisted multiple efforts to remove it from Creech’s computers, network security specialists say. And the infection underscores the ongoing security risks in what has become the U.S. military’s most important weapons system.

“We keep wiping it off, and it keeps coming back,” says a source familiar with the network infection, one of three that told Danger Room about the virus. “We think it’s benign. But we just don’t know.”

Military network security specialists aren’t sure whether the virus and its so-called “keylogger” payload were introduced intentionally or by accident; it may be a common piece of malware that just happened to make its way into these sensitive networks. The specialists don’t know exactly how far the virus has spread. But they’re sure that the infection has hit both classified and unclassified machines at Creech. That raises the possibility, at least, that secret data may have been captured by the keylogger, and then transmitted over the public internet to someone outside the military chain of command.

Drones have become America’s tool of choice in both its conventional and shadow wars, allowing U.S. forces to attack targets and spy on its foes without risking American lives. Since President Obama assumed office, a fleet of approximately 30 CIA-directed drones have hit targets in Pakistan more than 230 times; all told, these drones have killed more than 2,000 suspected militants and civilians, according to the Washington Post. More than 150 additional Predator and Reaper drones, under U.S. Air Force control, watch over the fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq. American military drones struck 92 times in Libya between mid-April and late August. And late last month, an American drone killed top terrorist Anwar al-Awlaki — part of an escalating unmanned air assault in the Horn of Africa and southern Arabian peninsula.

But despite their widespread use, the drone systems are known to have security flaws. Many Reapers and Predators don’t encrypt the video they transmit to American troops on the ground. In the summer of 2009, U.S. forces discovered “days and days and hours and hours” of the drone footage on the laptops of Iraqi insurgents. A $26 piece of software allowed the militants to capture the video.

The lion’s share of U.S. drone missions are flown by Air Force pilots stationed at Creech, a tiny outpost in the barren Nevada desert, 20 miles north of a state prison and adjacent to a one-story casino. In a nondescript building, down a largely unmarked hallway, is a series of rooms, each with a rack of servers and a “ground control station,” or GCS. There, a drone pilot and a sensor operator sit in their flight suits in front of a series of screens. In the pilot’s hand is the joystick, guiding the drone as it soars above Afghanistan, Iraq, or some other battlefield.

Some of the GCSs are classified secret, and used for conventional warzone surveillance duty. The GCSs handling more exotic operations are top secret. None of the remote cockpits are supposed to be connected to the public internet. Which means they are supposed to be largely immune to viruses and other network security threats.

But time and time again, the so-called “air gaps” between classified and public networks have been bridged, largely through the use of discs and removable drives. In late 2008, for example, the drives helped introduce the agent.btz worm to hundreds of thousands of Defense Department computers. The Pentagon is still disinfecting machines, three years later.

Use of the drives is now severely restricted throughout the military. But the base at Creech was one of the exceptions, until the virus hit. Predator and Reaper crews use removable hard drives to load map updates and transport mission videos from one computer to another. The virus is believed to have spread through these removable drives. Drone units at other Air Force bases worldwide have now been ordered to stop their use.

In the meantime, technicians at Creech are trying to get the virus off the GCS machines. It has not been easy. At first, they followed removal instructions posted on the website of the Kaspersky security firm. “But the virus kept coming back,” a source familiar with the infection says. Eventually, the technicians had to use a software tool called BCWipe to completely erase the GCS’ internal hard drives. “That meant rebuilding them from scratch” — a time-consuming effort.

The Air Force declined to comment directly on the virus. “We generally do not discuss specific vulnerabilities, threats, or responses to our computer networks, since that helps people looking to exploit or attack our systems to refine their approach,” says Lt. Col. Tadd Sholtis, a spokesman for Air Combat Command, which oversees the drones and all other Air Force tactical aircraft. “We invest a lot in protecting and monitoring our systems to counter threats and ensure security, which includes a comprehensive response to viruses, worms, and other malware we discover.”

However, insiders say that senior officers at Creech are being briefed daily on the virus.

“It’s getting a lot of attention,” the source says. “But no one’s panicking. Yet.”

Wednesday, October 05. 2011

What is Apple’s Siri, and will anyone use her?

By Sebastian Anthony

-----

The Apple “Let’s Talk iPhone” event has concluded. Tim Cook and a slew of Apple execs have taken it in turns to tell us about the latest and greatest Apple goodies, and rather underwhelmingly there’s no iPhone 5 and just significant takeaways: a cheaper and faster iPhone 4S, and an interesting software package called Siri. You can read all about the iPhone 4S on our sister sites Geek and PC Mag — here we’re going to talk about Siri.

If we look past the rather Indian (and feminine) name, Siri is a portable (and pocketable) virtual personal assistant. She has a speech-recognition module which works out what you’re saying, and then a natural language parser combs through your words to work out what you’re trying to do. Finally, an artificial intelligence gathers the possible responses and works out which one is most likely to be accurate, given the context, your geographical location, iOS’s current state, and so on.

Siri

is, in essence, a computer that you can interrogate for answers, kind

of like a search engine that runs locally on your phone. If you’ve seen IBM’s Watson play Jeopardy,

Siri is basically a cut-down version. She isn’t intelligent per se, but

if she has access to enough data, she can certainly appear intelligent.

Siri’s data sources are open APIs, like Wikipedia or Wolfram Alpha, and

in theory there’s no limit to the number of sources that can be added

(though it does require significant developer time to add a new data

set). For now you can ask Siri about the weather or the definition of a

word, but in the future, if Apple links Siri up to United Airlines,

you’ll be able to book a plane ticket, just by talking. Because Siri

runs locally, she can also send SMSes or set reminders, or anything else

that Apple (or app developers) allow her to do.

Siri

is, in essence, a computer that you can interrogate for answers, kind

of like a search engine that runs locally on your phone. If you’ve seen IBM’s Watson play Jeopardy,

Siri is basically a cut-down version. She isn’t intelligent per se, but

if she has access to enough data, she can certainly appear intelligent.

Siri’s data sources are open APIs, like Wikipedia or Wolfram Alpha, and

in theory there’s no limit to the number of sources that can be added

(though it does require significant developer time to add a new data

set). For now you can ask Siri about the weather or the definition of a

word, but in the future, if Apple links Siri up to United Airlines,

you’ll be able to book a plane ticket, just by talking. Because Siri

runs locally, she can also send SMSes or set reminders, or anything else

that Apple (or app developers) allow her to do.

Artificial intelligence isn’t cheap in terms of processing power, though: Siri is expected to only run on the iPhone 4S, which sports a new and significantly faster processor than its predecessors, the A5. Siri probably makes extensive use of Apple’s new cloud computer cluster, too, much in the same way that Amazon Silk splits web browsing between the cloud and the local device.

Noise

That’s enough about what Siri is and how it works. Let’s talk about whether anyone will actually use Siri, which is fundamentally a glorified voice control search engine. Voice commands have existed in some semblance since at least as far back as the Nokia 3310, which was released in 2000. Almost every phone since then has had the ability to voice dial, or in the case of modern smartphones, voice activate apps and features.

When was the last time you saw someone talk to their phone? Driving and other hands-otherwise-occupied activities don’t count. When was the last time you walked down the street and heard someone loudly dictate “call mom” into their phone? Can you really see yourself saying “Siri, I want a kebab” in public?

It might lose its social stigma if everyone talks to their phone, but isn’t it already annoying enough that people swan down streets with hands-free headsets, blabbing away? It’s not like voice recognition is at the stage where you can whisper or mumble a command into your phone, either: you’re going to have to say, nice and clearly, “how do I get to the bank?” in public. Now imagine that you’ve just walked past the guy who’s talking to Siri — is he asking you for directions, or Siri? Now imagine what it would be like if everyone around you is having a one-sided phone conversation or talking to Siri.

Finally, there’re practical implications to consider, which Apple usually ignores in its press events. For example, will Siri only recognize my voice? What if I leave my phone in the living room and my girlfriend shouts out “honey, we should go to that Italian restaurant” — will Siri then make a reservation? On a more nefarious note, will my wife be able to say “Siri, show me my husband’s hidden email.” When walking down a street, will Siri overhear other conversations and react accordingly?

Siri will be fantastic in the car, that’s for certain. She will also be very accommodating when you’re on your own — imagine shouting across the room “Siri, do I need to wear a jacket today?” or “Siri, download the latest episode of Glee.” Siri will be unusable in public, though, while on the move — and that’s the one time where you really don’t want to be looking down at that darn on-screen keyboard.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131057)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101671)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100067)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57900)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57463)

Categories

Show tagged entries

Syndicate This Blog

Calendar

|

|

February '26 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |