Thursday, March 28. 2013

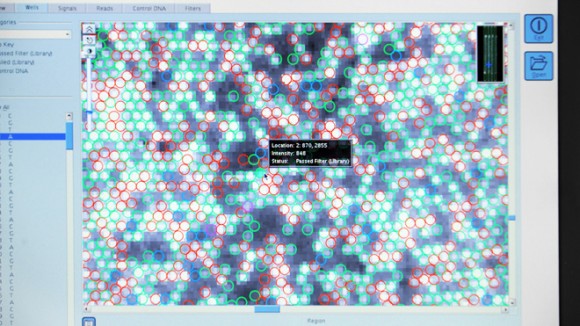

Internet Census 2012 - Port scanning /0 using insecure embedded devices

-----

Abstract While playing around with the Nmap Scripting Engine

(NSE) we discovered an amazing number of open embedded devices on the

Internet. Many of them are based on Linux and allow login to standard

BusyBox with empty or default credentials. We used these devices to

build a distributed port scanner to scan all IPv4 addresses. These scans

include service probes for the most common ports, ICMP ping, reverse

DNS and SYN scans. We analyzed some of the data to get an estimation of

the IP address usage.

All data gathered during our research is released into the public domain for further study.

Continue reading "Internet Census 2012 - Port scanning /0 using insecure embedded devices"

The Internet is not a Surveillance State…

Via Telekomunnisten

-----

In his March 16, 2013 opinion column on CNN.com,

Bruce Schneier called the Internet a “surveillance state”. In the

piece, Schneier complains that the Internet now serves as a platform

which enables massive and pervasive surveillance by the state. State

sponsored and ordained surveillance, however, is not synonymous with the

Internet. Schneier’s use of the word ‘state’ is ill-advised, his

goading conclusion thereby misses the mark.

The Internet is not a State. States can do something to limit the invasiveness of web-based services used in the public and private sectors alike, but they won’t, because any vision of infinite prosperity based on digital-age intellectual property rights and patents relies on the current content-control model of value extraction (of which Internet use, more accurately web use, is the most mass-culture manifestation) not only persisting but becoming ever more prevalent.

Web-based service providers such as Facebook and Google are not the Internet, but rather are web-based platforms built on the Internet. The superior user-experience of such services accrues a dedicated user base for basic communication functionalities. The design idiosyncrasies of these platforms define popular culture. However just because certain service providers have become dominant does not mean that the techniques or strategies they employ are fundamentally superior. These have become dominant because they have evolved a business model which ensures a generous ROI. Without exception, the leading platforms ensure value for their investors by trading in user data.

There are myriad ways to use the Internet, there are myriad different paradigms for Internet-enabled communication, collaboration and other social activities which can and are being explored. Whether or not they can “compete” with the Googles and Facebooks, depends today entirely on whether they can produce sufficient “surplus value” to satisfy investors, thereby to attract sufficient funding to produce superior user experience. In all the world wide web there is not a model for this which is not centered on the harvesting and analysis of user data.

Since much of the world already finds itself on the ‘client’ side of automated services for much of their waking life, the competition is on to deliver the “highest quality” of such service, anticipating client’s predilections and desires. In other words, as everybody knows, the old customer service saw recurs, “please excuse the inconvenience, we are … to serve you better”. The qualms one has about permitting unmitigated and unmonitored access to one’s social life are discounted as a mere inconvenience one must endure so that the machines can “serve us better”.

The state likewise asks us to put up with the invasion of privacy in order to provide us with such things as “security” and “democracy”. If we look closely at those two commodities we are being offered in exchange for our private sphere, we may not be so sure of the fairness of the deal. “Security” for one, may come in myriad forms, but the form of “security” which is offered to us is one determined through lobbying by security companies, which, no surprise, promise to offer us better service the more we open up our lives to data collection.

The Internet is not a ‘state’, it can be ruled over by states, but in principle, it belongs to all humanity. The Internet is not an ephemeral service, it is a network of very real, material computers which are located indisputably in specific real material buildings at specific real material locations, under nominally specific local, regional, national and international jurisdictions, right now. There is nothing fundamentally abstract about the Internet, it is as hard to fathom as the electricity grid on which it is practically dependent.

States can produce and maintain infrastructure like electricity grids and networked computers connected in the Internet. They can, but, today, the tendency is for states to delegate private entities to do this. This is said to be more efficient. Popular dictum is that the price to pay for such services is privacy. States have traditionally been moderate in exacting that price for fear of incurring the wrath of the populace. Private entities which belong to no particular state, when and if they incur such wrath, pretend it is up to the state to moderate their behaviour. Privately, the actors for state are discouraged to regulate for fear of inhibiting “prosperity”.

Therefore, states are increasingly impotent to rule over the Internet. The Internet has become a surveillance system used by private companies and their clients, the states, alike “to serve you better”. Behind this innocuous promise, the knowledge about private citizens is used to hone customized media designed to compel users to purchase anything from clothes to security to ideology. The big-data industries will build the patented processes which transform data mined from users into patented automated services. This is advertised as the keystone of the 21st century economy. In the perpetual panic of austerity finance capitalism, who would dare embolden the state to emperil the perceived slim auspices of escape from financial ruin the surveillance/data-collection industry-driven economy offers us?

But the Internet is not a surveillance state. The Internet, as described in the article, has come to be used as a most efficient technology for pervasive data surveillance. States use surveillance technologies when they are available to the degree that the laws permit. Today’s laws permit private companies to do things with surveillance data the state traditionally cannot without going through lengthy legislative approval processes. It is through the obligation to produce profits that private companies have been permitted to transgress legal limits on invasion of privacy. The private companies have thus played a vanguard role in loosening up legal restrictions protecting individual privacy.

Surveillance at work has long been accepted as integral to taylorist notions of efficiency and productivity. Now that the work place has extended to be almost indistinguishable with daily life, the fact that surveillance has followed along seems unsurprising. While mobile computer were advertised to liberate us from the cubicle, it has made for an environment where one’s employment is perpetual, again, it is no surprise then that surveillance technologies have followed.

As business rationale and strategies evolve, as the boundaries between work time and leisure time dissolves, enterprise ethics entrench themselves in every aspect of social life, and surveillance has followed, if only so that the instruments on which one coordinate’s one work-leisure hybridity can “serve you better”. So the prevalence of surveillance is a consequence of the interspersal of productive labour time in life time. Ironically the call from the left to integrate and acknowledge so-called affective labour will have as the main notable outcome that these activities will become subject to data-acquisition monetization and surveillance.

Bifo noted in a recent speech that in 1977 he was (radically) militating against the traditional career-work regime, where people spent their entire adult lives working for a particular company. Now it is not without some bitterness that he notes, bursting the worker out of the workplace has resulted in today’s worker having to work for numerous companies all the time.

The government’s own performance is measured through massive-scale data acquisition. This data-acquisition is indistinguishable from surveillance, the surveillance permits the government to detect, intervene with, and if necessary terminate its own practices which are determined to be inefficient, or counter-productive. Therefore the government, in order to prove to the citizens that it is doing a good job, exploits all the opportunities for surveillance opened up by vanguardist capital.

But the Internet is just a network of computers, which provides functionalities. It is not a state. The state could, in principle, elect not to use the Internet for surveillance, and could restrict the data-collection activities of private service providers. I have outlined above why this is unlikely, but it is possible. Private capital would likely take revenge on such a government, and the citizens would likely come to disdain its decision. Under global capital there really is little alternative for states to “keeping up with the Joneses’” surveillance service industry. Massive pervasive surveillance is understood simply as a precondition to prosperity.

“Welcome to an Internet without privacy, and we’ve ended up here with hardly a fight.”-Bruce Schneier

One wonders who Bruce Schneier refers to with the pronoun “we” in his parting shot. Certainly prominent organisations such as EFF in the USA and Open Rights Group in the UK have been working for years to help web users appreciate and understand the latest online privacy concerns, among other burning issues of the digital age. And there are thousands of initiatives around the world working to criticize and raise concerns about the egregious asymmetries of power on the web. High-profile conferences and actions are organised, excellently researched publications are made available, yet these initiatives get only muted coverage in the mass media.

The problem is not for lack of trying, besides whatever bias the corporate-controlled mass media outlets may exercise, it is also due to the fact that these critical organizations rely on people to contribute voluntarily, in their spare time. In other words, dissent, alternative viewpoints, proposals and even services cannot compete. The industry or economy which sees its success as contingent on ever more pervasive data-collection from individuals is unlikely to finance critical initiatives to the extent that these might hire more paid staff, and thereby make their contributions more attractive, accessible and appreciated. The state may step in here and subsidize such critical organizations to some degree, but only under severe admonishment from the dominant web-service industries.

Networked-service and networked-content businesses with their increasingly data-acquisition-oriented profit models have become extremely important and influential in national economies. If Bruce Schneier is sincere about protecting online privacy, he had better look not to the state, but to the capitalist conditions of the production of web services which compel corporations to develop, implement and constantly improve the invasive practices that offend his sensibility.

Tuesday, March 26. 2013

Complete Neanderthal genome published by German researchers

Via Slash Gear

-----

A group of German researchers announced this week that they have completed sequencing of a Neanderthal genome. The scientists say that the high-quality sequencing will be made available online for other researchers and scientists to study. The researchers were able to produce the genome using a toe bone found in a Siberian cave.

This published genome is said to be far more detailed than a previous “draft” Neanderthal genome was sequenced three years ago by the same team. The group of researchers operate from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. The researchers say that the new genome allows individual inherited traits from the Neanderthal’s mother and father to be distinguished.

In the future, the scientists hope to compare their new genome sequence to that of other Neanderthals as well as comparing the genome to another extinct human species with remains that were found in the same Siberian cave. The other remains are of an extinct human species called Denisovan. Certainly some researchers will compare this new genome to that of humans.

The group of researchers intends to publish a scientific paper based on new knowledge gained from studying the detailed genome. Specifically the researchers plan to refine knowledge having to do with genetic changes that occur in the genomes of modern humans after they parted ways with Neanderthals and Denisovians.

Thursday, March 07. 2013

When are we going to learn to trust robots?

Via BBC

-----

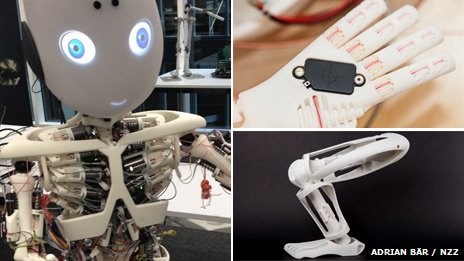

A new robot unveiled this week highlights the psychological and technical challenges of designing a humanoid that people actually want to have around.

Like all little boys, Roboy likes to show off.

He can say a few words. He can shake hands and wave. He is learning to ride a tricycle. And - every parent's pride and joy - he has a functioning musculoskeletal anatomy.

But when Roboy is unveiled this Saturday at the Robots on Tour event in Zurich, he will be hoping to charm the crowd as well as wow them with his skills.

"One of the goals is for Roboy to be a messenger of a new generation of robots that will interact with humans in a friendly way," says Rolf Pfeifer from the University of Zurich - Roboy's parent-in-chief.

As manufacturers get ready to market robots for the home it has become essential for them to overcome the public's suspicion of them. But designing a robot that is fun to be with - as well as useful and safe - is quite difficult.

-----

The uncanny valley: three theories

Researchers have speculated about why we might feel uneasy in the presence of realistic robots.

- They remind us of corpses or zombies

- They look unwell

- They do not look and behave as expected

-----

Roboy's main technical innovation is a tendon-driven design that mimics the human muscular system. Instead of whirring motors in the joints like most robots, he has around 70 imitation muscles, each containing motors that wind interconnecting tendons. Consequently, his movements will be much smoother and less robotic.

But although the technical team was inspired by human beings, it chose not to create a robot that actually looked like one. Instead of a skin-like covering, Roboy has a shiny white casing that proudly reveals his electronic innards.

Behind this design is a long-standing hypothesis about how people feel in the presence of robots.

In 1970, the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori speculated that the more lifelike robots become, the more human beings feel familiarity and empathy with them - but that a robot too similar to a human provokes feelings of revulsion.

Mori called this sudden dip in human beings' comfort levels the "uncanny valley".

"There are quite a number of studies that suggest that as long as people can clearly see that the robot is a machine, even if they project their feelings into it, then they feel comfortable," says Pfeifer.

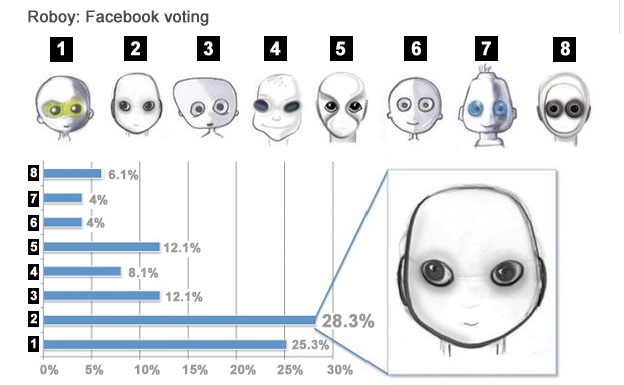

Roboy was styled as a boy - albeit quite a brawny one - to lower his perceived threat levels to humans. His winsome smile - on a face picked by Facebook users from a selection - hasn't hurt the team in their search for corporate sponsorship, either.

But the image problem of robots is not just about the way they look. An EU-wide survey last year found that although most Europeans have a positive view of robots, they feel they should know their place.

Eighty-eight per cent of respondents agreed with the statement that robots are "necessary as they can do jobs that are too hard or dangerous for people", such as space exploration, warfare and manufacturing. But 60% thought that robots had no place in the care of children, elderly people and those with disabilities.

The computer scientist and psychologist Noel Sharkey has, however, found 14 companies in Japan and South Korea that are in the process of developing childcare robots.

South Korea has already tried out robot prison guards, and three years ago launched a plan to deploy more than 8,000 English-language teachers in kindergartens.

-----

A robot buddy?

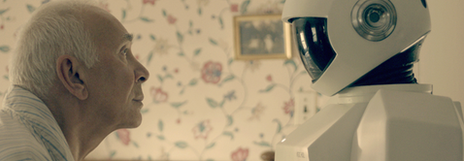

- In the film Robot and Frank, set in the near-future, ageing burglar Frank is provided with a robot companion to be a helper and nurse when he develops dementia

- The story plays out rather like a futuristic buddy movie - although he is initially hostile to the robot, Frank is soon programming him to help him in his schemes, which are not entirely legal

-----

Cute, toy-like robots are already available for the home.

Take the Hello Kitty robot, which has been on the market for several years and is still available for around $3,000 (£2,000). Although it can't walk, it can move its head and arms. It also has facial recognition software that allows it to call children by name and engage them in rudimentary conversation.

A tongue-in-cheek customer review of the catbot on Amazon reveals a certain amount of scepticism.

"Hello Kitty Robo me was babysit," reads the review.

"Love me hello kitty robo, thank robo for make me talk good... Use lots battery though, also only for rich baby, not for no money people."

-----

Asimo

At just 130cm high, Honda's Asimo jogs around on bended knee like a mechanical version of Dobby, the house elf from Harry Potter. He can run, climb up and down stairs and pour a bottle of liquid in a cup.

Since 1986, Honda have been working on humanoids with the ultimate aim of providing an aid to those with mobility impairments.

-----

The product description says the robot is "a perfect companion for times when your child needs a little extra comfort and friendship" and "will keep your child happily occupied". In other words, it's something to turn on to divert your infant for a few moments, but it is not intended as a replacement child-minder.

An ethical survey of "robot nannies" by Noel and Amanda Sharkey suggests that as robots become more sophisticated parents may be increasingly tempted to hand them too much responsibility.

The survey also raises the question of what long-term effects will result from children forming an emotional bond with a lump of plastic. They cite one case study in which a 10-year-old girl, who had been given a robot doll for several weeks, reported that "now that she's played with me a lot more, she really knows me".

Noel Sharkey says that he loves the idea of children playing with robots but has serious concerns about them being brought up by them. "[Imagine] the kind of attachment disorders they would develop," he says.

But despite their limitations, humanoid robots might yet prove invaluable in narrow, fixed roles in hospitals, schools and homes.

"Something really interesting happens between some kids with autism and robots that doesn't happen between those children and other humans," says Maja J Mataric, a roboticist at the University of Southern California. She's found that such children respond positively to humanoids and she is trying to work out how they can be used therapeutically.

In their study, the Sharkeys make the observation that robots have one advantage over adult humans. They can have physical contact with children - something now frowned upon or forbidden in schools.

"These restrictions would not apply to a robot," they write, "because it could not be accused of having sexual intent and so there are no particular ethical concerns. The only concern would be the child's safety - for example, not being crushed by a hugging robot."

When it comes to robots, there is such a thing as too much love.

"If you were having a mechanical assistant in the home that was powerful enough to be useful, it would necessarily be powerful enough to be dangerous," says Peter Robinson of Cambridge University. "Therefore it'd better have really good understanding and communication."

His team are developing robots with sophisticated facial recognition. These machines won't just be able to tell Bill from Brenda but they will be able to infer from his expression whether Bill is feeling confused, tired, playful or in physical agony.

Roboy's muscles and tendons may actually make him a safer robot to have around. His limbs have more elasticity than a conventional robot's, allowing for movement even when he has a power failure.

Rolf Pfeifer has a favourite question which he puts to those sceptical about using robots in caring situations.

"If you couldn't walk upstairs any more, would you want a person to carry you or would you want to take the elevator?"

Most people opt for the elevator, which is - if you think about it - a kind of robot.

Pfeifer believes robots will enter our homes. What is not yet clear is whether the future lies in humanoid servants with a wide range of limited skills or in intelligent, responsive appliances designed to do specific tasks, he says.

"I think the market will ultimately determine what kind of robot we're going to have."

You can listen to Click on the BBC World Service. Listen back to the robots for humans special via iplayer or browse the Click podcast archive.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (130547)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (100313)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (99486)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (56810)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (56542)