Via IEEE Spectrum

-----

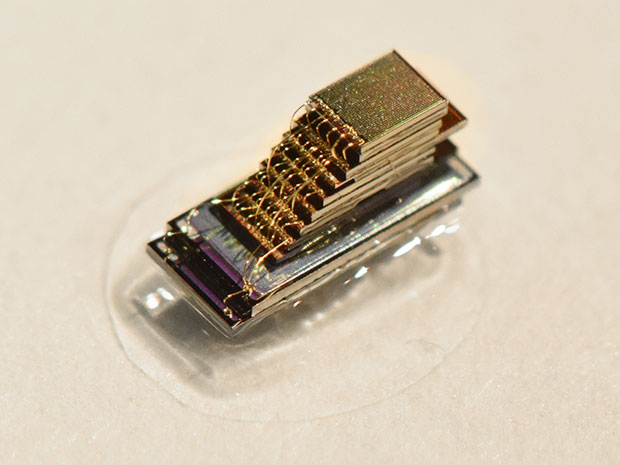

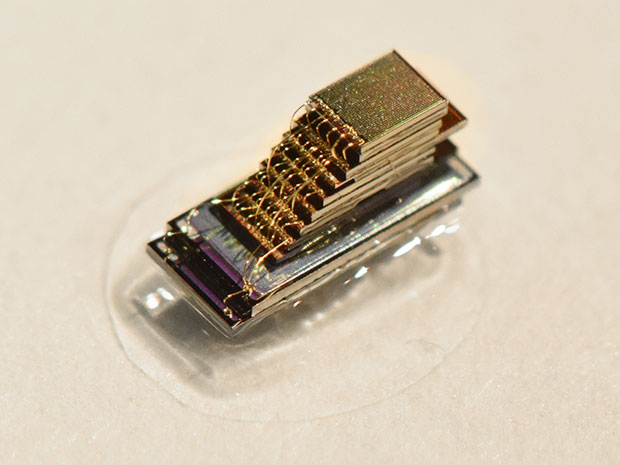

Photo: University of Michigan and TSMC

One of several varieties of University of Michigan micromotes. This one incorporates 1 megabyte of flash memory.

Computer scientist David Blaauw

pulls a small plastic box from his bag. He carefully uses his

fingernail to pick up the tiny black speck inside and place it on the

hotel café table. At 1 cubic millimeter, this is one of a line of the

world’s smallest computers. I had to be careful not to cough or sneeze

lest it blow away and be swept into the trash.

Blaauw and his colleague Dennis Sylvester,

both IEEE Fellows and computer scientists at the University of

Michigan, were in San Francisco this week to present 10 papers related

to these “micromote” computers at the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC). They’ve been presenting different variations on the tiny devices for a few years.

Their broader goal is to make smarter, smaller sensors for medical

devices and the Internet of Things—sensors that can do more with less

energy. Many of the microphones, cameras, and other sensors that make up

the eyes and ears of smart devices are always on alert, and frequently

beam personal data into the cloud because they can’t analyze it

themselves. Some have predicted that by 2035, there will be 1 trillion such devices.

“If you’ve got a trillion devices producing readings constantly, we’re

going to drown in data,” says Blaauw. By developing tiny,

energy-efficient computing sensors that can do analysis on board, Blaauw

and Sylvester hope to make these devices more secure, while also saving

energy.

At the conference, they described micromote designs that use only a

few nanowatts of power to perform tasks such as distinguishing the sound

of a passing car and measuring temperature and light levels. They

showed off a compact radio that can send data from the small computers

to receivers 20 meters away—a considerable boost compared to the

50-centimeter range they reported last year at ISSCC. They also described their work with TSMC

(Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) on embedding flash memory

into the devices, and a project to bring on board dedicated, low-power

hardware for running artificial intelligence algorithms called deep

neural networks.

Blaauw and Sylvester say they take a holistic approach to adding new

features without ramping up power consumption. “There’s no one answer”

to how the group does it, says Sylvester. If anything, it’s “smart

circuit design,” Blaauw adds. (They pass ideas back and forth rapidly,

not finishing each other’s sentences but something close to it.)

The memory research is a good example of how the right trade-offs can

improve performance, says Sylvester. Previous versions of the

micromotes used 8 kilobytes of SRAM (static RAM), which makes for a

pretty low-performance computer. To record video and sound, the tiny

computers need more memory. So the group worked with TSMC to bring flash

memory on board. Now they can make tiny computers with 1 megabyte of

storage.

Flash can store more data in a smaller footprint than SRAM, but it

takes a big burst of power to write to the memory. With TSMC, the group

designed a new memory array that uses a more efficient charge pump for

the writing process. The memory arrays are a bit less dense than TSMC’s

commercial products, for example, but still much better than SRAM. “We

were able to get huge gains with small trade-offs,” says Sylvester.

Another micromote they presented at the ISSCC incorporates a deep-learning

processor that can operate a neural network while using just 288

microwatts. Neural networks are artificial intelligence algorithms that

perform well at tasks such as face and voice recognition. They typically

demand both large memory banks and intense processing power, and so

they’re usually run on banks of servers often powered by advanced GPUs.

Some researchers have been trying to lessen the size and power demands

of deep-learning AI with dedicated hardware that’s specially designed to

run these algorithms. But even those processors still use over 50

milliwatts of power—far too much for a micromote. The Michigan group

brought down the power requirements by redesigning the chip

architecture, for example by situating four processing elements within

the memory (in this case, SRAM) to minimize data movement.

The idea is to bring neural networks to the Internet of Things. “A

lot of motion detection cameras take pictures of branches moving in the

wind—that’s not very helpful,” says Blaauw. Security cameras and other

connected devices are not smart enough to tell the difference between a

burglar and a tree, so they waste energy sending uninteresting footage

to the cloud for analysis. Onboard deep-learning processors could make

better decisions, but only if they don’t use too much power. The

Michigan group imagine that deep-learning processors could be integrated

into many other Internet-connected things besides security systems. For

example, an HVAC system could decide to turn the air-conditioning down

if it sees multiple people putting on their coats.

After demonstrating many variations on these micromotes in an

academic setting, the Michigan group hopes they will be ready for market

in a few years. Blaauw and Sylvester say their startup company, CubeWorks,

is currently prototyping devices and researching markets. The company

was quietly incorporated in late 2013. Last October, Intel Capital announced they had invested an undisclosed amount in the tiny computer company.