Entries tagged as monitoring

hardware 3d 3d printing 3d scanner ad ai amd android api apple ar arduino army artificial intelligence asus augmented reality automation camera car chrome cloud health innovation&society mobile privacy sensors technology advertisements algorythm amazon API art big data book browser cloud computing code computer history data visualisation DNA facial recognition genome google hack network picture programming search security

Monday, April 28. 2014

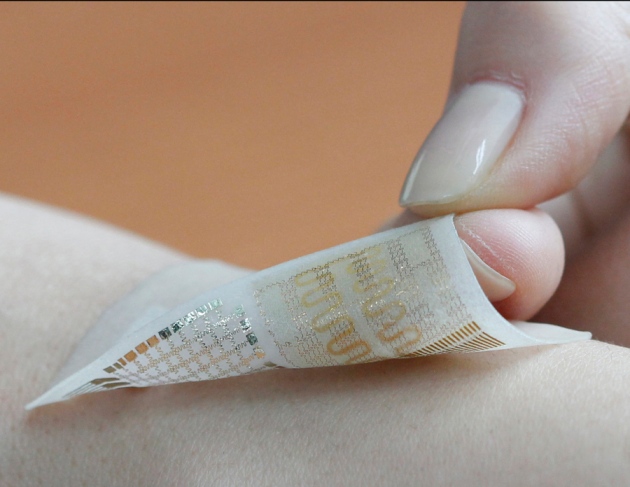

‘Electronic skin' equipped with memory

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (129276)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (97970)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (94464)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (55659)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (50693)

Categories

Show tagged entries

Calendar

|

|

July '24 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||