Via Mark Shuttleworth

-----

The desktop remains central to our everyday work and play, despite

all the excitement around tablets, TV’s and phones. So it’s exciting for

us to innovate in the desktop too, especially when we find ways to

enhance the experience of both heavy “power” users and casual users at

the same time. The desktop will be with us for a long time, and for

those of us who spend hours every day using a wide diversity of

applications, here is some very good news: 12.04 LTS will include the

first step in a major new approach to application interfaces.

This work grows out of observations of new and established /

sophisticated users making extensive use of the broader set of

capabilities in their applications. We noticed that both groups of users

spent a lot of time, relatively speaking, navigating the menus of their

applications, either to learn about the capabilities of the app, or to

take a specific action. We were also conscious of the broader theme in

Unity design of leading from user intent. And that set us on a course

which lead to today’s first public milestone on what we expect will be a

long, fruitful and exciting journey.

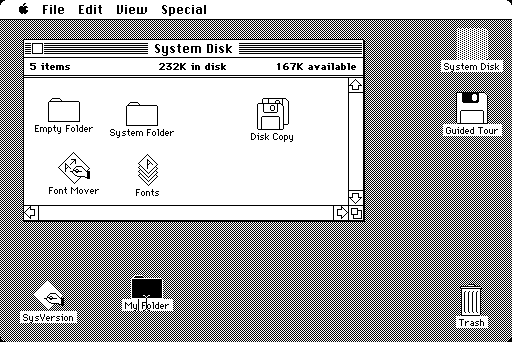

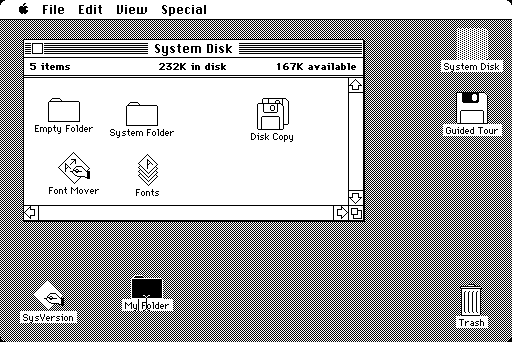

The menu has been a central part of the GUI since Xerox PARC invented ‘em in the 70?s. It’s the M in WIMP and has been there, essentially unchanged, for 30 years.

The original Macintosh desktop, circa 1984, courtesy of Wikipedia

We can do much better!

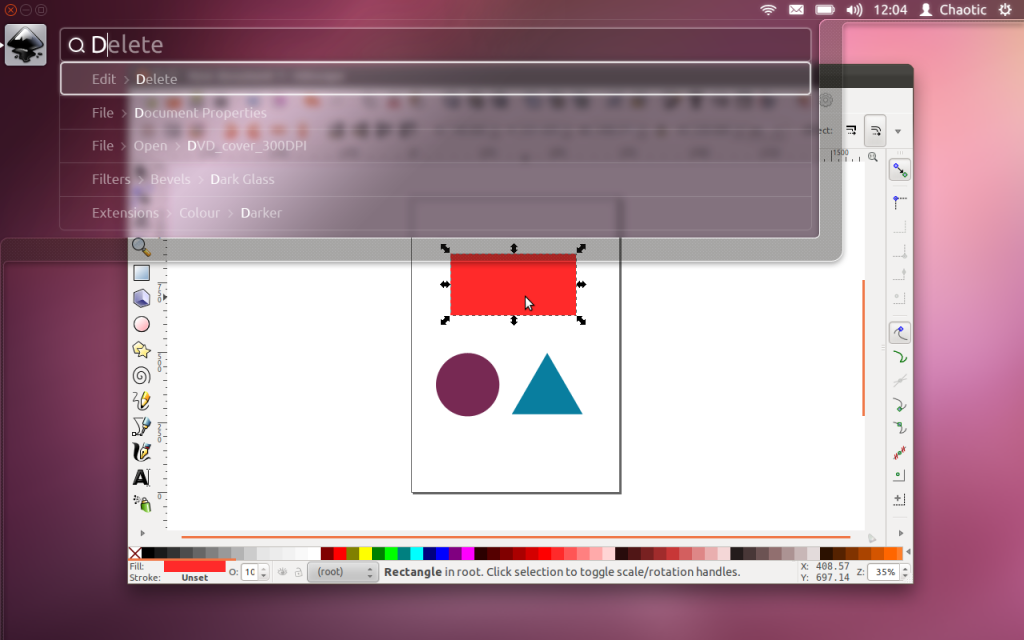

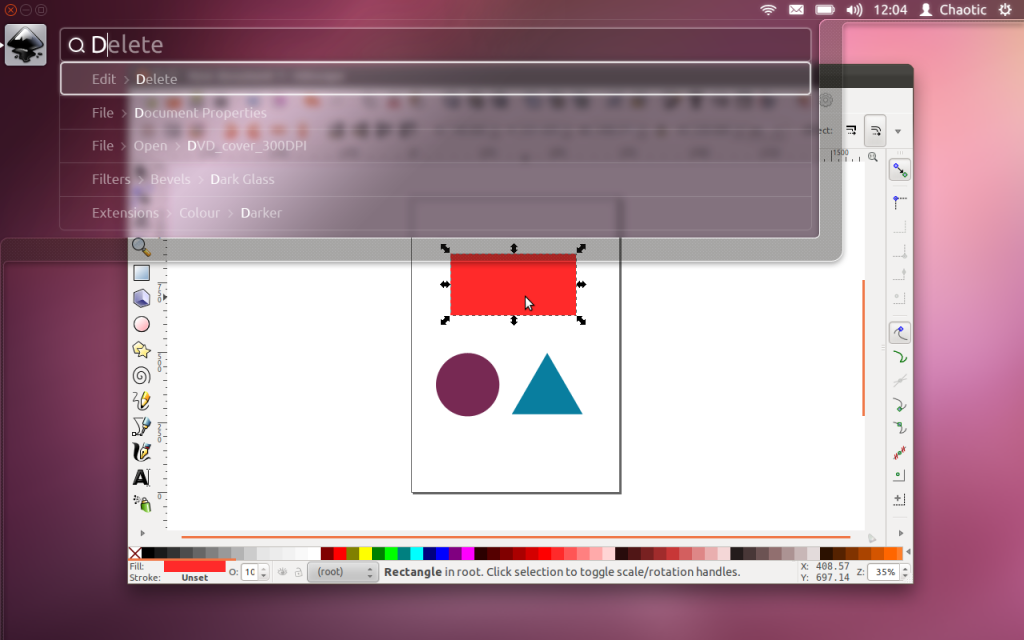

Say hello to the Head-Up Display, or HUD, which will ultimately replace menus in Unity applications. Here’s what we hope you’ll see in 12.04 when you invoke the HUD from any standard Ubuntu app that supports the global menu:

Snapshot of the HUD in Ubuntu 12.04

The intenterface – it maps your intent to the interface

This is the HUD. It’s a way for you to express your intent and

have the application respond appropriately. We think of it as “beyond

interface”, it’s the “intenterface”. This concept of “intent-driven

interface” has been a primary theme of our work in the Unity shell, with

dash search as a first class experience pioneered in Unity. Now we are

bringing the same vision to the application, in a way which is

completely compatible with existing applications and menus.

The HUD concept has been the driver for all the work we’ve done in

unifying menu systems across Gtk, Qt and other toolkit apps in the past

two years. So far, that’s shown up as the global menu. In 12.04, it also

gives us the first cut of the HUD.

Menus serve two purposes. They act as a standard way to invoke commands which are too infrequently used to warrant a dedicated piece of UI real-estate, like a toolbar button, and they serve as a map of the app’s functionality,

almost like a table of contents that one can scan to get a feel for

‘what the app does’. It’s command invocation that we think can be

improved upon, and that’s where we are focusing our design exploration.

As a means of invoking commands, menus have some advantages. They are

always in the same place (top of the window or screen). They are

organised in a way that’s quite easy to describe over the phone, or in a

text book (“click the Edit->Preferences menu”), they are pretty fast

to read since they are generally arranged in tight vertical columns.

They also have some disadvantages: when they get nested, navigating the

tree can become fragile. They require you to read a lot when you

probably already know what you want. They are more difficult to use from

the keyboard than they should be, since they generally require you to

remember something special (hotkeys) or use a very limited subset of the

keyboard (arrow navigation). They force developers to make often

arbitrary choices about the menu tree (“should Preferences be in Edit or

in Tools or in Options?”), and then they force users to make equally

arbitrary effort to memorise and navigate that tree.

The HUD solves many of these issues, by connecting users directly to what they want. Check out the video,

based on a current prototype. It’s a “vocabulary UI”, or VUI, and

closer to the way users think. “I told the application to…” is common

user paraphrasing for “I clicked the menu to…”. The tree is no longer

important, what’s important is the efficiency of the match between what

the user says, and the commands we offer up for invocation.

In 12.04 LTS, the HUD is a smart look-ahead search through the app

and system (indicator) menus. The image is showing Inkscape, but of

course it works everywhere the global menu works. No app modifications

are needed to get this level of experience. And you don’t have to adopt

the HUD immediately, it’s there if you want it, supplementing the

existing menu mechanism.

It’s smart, because it can do things like fuzzy matching, and it can learn what you usually do

so it can prioritise the things you use often. It covers the focused

app (because that’s where you probably want to act) as well as system

functionality; you can change IM state, or go offline in Skype, all

through the HUD, without changing focus, because those apps all talk to

the indicator system. When you’ve been using it for a little while it

seems like it’s reading your mind, in a good way.

We’ll resurrect the (boring) old ways of displaying the menu in

12.04, in the app and in the panel. In the past few releases of Ubuntu,

we’ve actively diminished the visual presence of menus in anticipation

of this landing. That proved controversial. In our defence, in user

testing, every user finds the menu in the panel, every time, and it’s

obviously a cleaner presentation of the interface. But hiding the menu

before we had the replacement was overly aggressive. If the HUD lands in

12.04 LTS, we hope you’ll find yourself using the menu less and less,

and be glad to have it hidden when you are not using it. You’ll

definitely have that option, alongside more traditional menu styles.

Voice is the natural next step

Searching is fast and familiar, especially once we integrate voice

recognition, gesture and touch. We want to make it easy to talk to any

application, and for any application to respond to your voice. The full

integration of voice into applications will take some time. We can start

by mapping voice onto the existing menu structures of your apps. And it

will only get better from there.

But even without voice input, the HUD is faster than mousing through a

menu, and easier to use than hotkeys since you just have to know what

you want, not remember a specific key combination. We can search through

everything we know about the menu, including descriptive help text, so

pretty soon you will be able to find a menu entry using only vaguely

related text (imagine finding an entry called Preferences when you

search for “settings”).

There is lots to discover, refine and implement. I have a feeling this will be a lot of fun in the next two years

Even better for the power user

The results so far are rather interesting: power users say things

like “every GUI app now feels as powerful as VIM”. EMACS users just

grunt and… nevermind  . Another comment was “it works so well that the rare occasions when it

can’t read my mind are annoying!”. We’re doing a lot of user testing on

heavy multitaskers, developers and all-day-at-the-workstation personas

for Unity in 12.04, polishing off loose ends in the experience that

frustrated some in this audience in 11.04-10. If that describes you, the

results should be delightful. And the HUD should be particularly

empowering.

. Another comment was “it works so well that the rare occasions when it

can’t read my mind are annoying!”. We’re doing a lot of user testing on

heavy multitaskers, developers and all-day-at-the-workstation personas

for Unity in 12.04, polishing off loose ends in the experience that

frustrated some in this audience in 11.04-10. If that describes you, the

results should be delightful. And the HUD should be particularly

empowering.

Even casual users find typing faster than mousing. So while there are

modes of interaction where it’s nice to sit back and drive around with

the mouse, we observe people staying more engaged and more focused on

their task when they can keep their hands on the keyboard all the time.

Hotkeys are a sort of mental gymnastics, the HUD is a continuation of

mental flow.

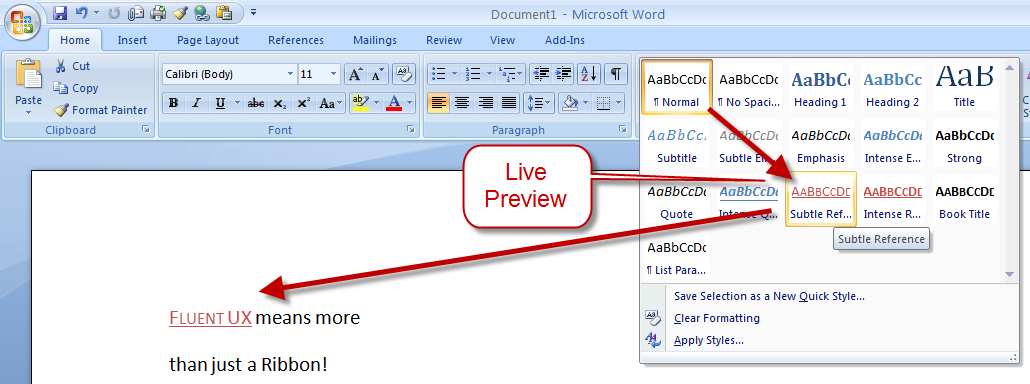

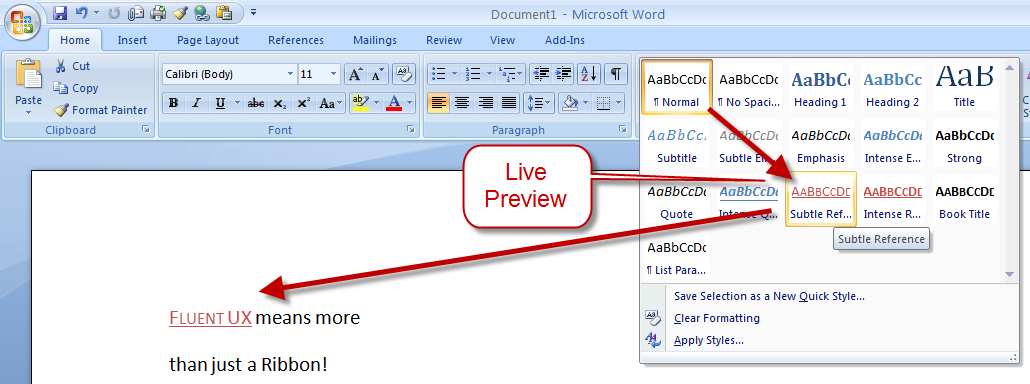

Ahead of the competition

There are other teams interested in a similar problem space. Perhaps

the best-known new alternative to the traditional menu is Microsoft’s

Ribbon. Introduced first as part of a series of changes called Fluent UX

in Office, the ribbon is now making its way to a wider set of Windows

components and applications. It looks like this:

You can read about the ribbon from a supporter (like any UX change, it has its supporters and detractors  ) and if you’ve used it yourself, you will have your own opinion about

it. The ribbon is highly visual, making options and commands very

visible. It is however also a hog of space (I’m told it can be

minimised). Our goal in much of the Unity design has been to return

screen real estate to the content with which the user is working; the

HUD meets that goal by appearing only when invoked.

) and if you’ve used it yourself, you will have your own opinion about

it. The ribbon is highly visual, making options and commands very

visible. It is however also a hog of space (I’m told it can be

minimised). Our goal in much of the Unity design has been to return

screen real estate to the content with which the user is working; the

HUD meets that goal by appearing only when invoked.

Instead of cluttering up the interface ALL the time, let’s clear out

the chrome, and show users just what they want, when they want it.

Time will tell whether users prefer the ribbon, or the HUD, but we

think it’s exciting enough to pursue and invest in, both in R&D and

in supporting developers who want to take advantage of it.

Other relevant efforts include Enso and Ubiquity from the original Humanized team (hi Aza &co), then at Mozilla.

Our thinking is inspired by many works of science, art and

entertainment; from Minority Report to Modern Warfare and Jef Raskin’s

Humane Interface. We hope others will join us and accelerate the shift

from pointy-clicky interfaces to natural and efficient ones.

Roadmap for the HUD

There’s still a lot of design and code still to do. For a start, we

haven’t addressed the secondary aspect of the menu, as a visible map of

the functionality in an app. That discoverability is of course entirely

absent from the HUD; the old menu is still there for now, but we’d like

to replace it altogether not just supplement it. And all the other

patterns of interaction we expect in the HUD remain to be explored.

Regardless, there is a great team working on this, including folk who

understand Gtk and Qt such as Ted Gould, Ryan Lortie, Gord Allott and

Aurelien Gateau, as well as designers Xi Zhu, Otto Greenslade, Oren

Horev and John Lea. Thanks to all of them for getting this initial work

to the point where we are confident it’s worthwhile for others to invest

time in.

We’ll make sure it’s easy for developers working in any toolkit to

take advantage of this and give their users a better experience. And

we’ll promote the apps which do it best – it makes apps easier to use,

it saves time and screen real-estate for users, and it creates a better

impression of the free software platform when it’s done well.

From a code quality and testing perspective, even though we consider

this first cut a prototype-grown-up, folk will be glad to see this:

Overall coverage rate:

lines......: 87.1% (948 of 1089 lines)

functions..: 97.7% (84 of 86 functions)

branches...: 63.0% (407 of 646 branches)

Landing in 12.04 LTS is gated on more widespread testing. You can of course try this out from a PPA or branch the code in Launchpad (you will need these two branches). Or dig deeper with blogs on the topic from Ted Gould, Olli Ries and Gord Allott. Welcome to 2012 everybody!

. Another comment was “it works so well that the rare occasions when it

can’t read my mind are annoying!”. We’re doing a lot of user testing on

heavy multitaskers, developers and all-day-at-the-workstation personas

for Unity in 12.04, polishing off loose ends in the experience that

frustrated some in this audience in 11.04-10. If that describes you, the

results should be delightful. And the HUD should be particularly

empowering.

. Another comment was “it works so well that the rare occasions when it

can’t read my mind are annoying!”. We’re doing a lot of user testing on

heavy multitaskers, developers and all-day-at-the-workstation personas

for Unity in 12.04, polishing off loose ends in the experience that

frustrated some in this audience in 11.04-10. If that describes you, the

results should be delightful. And the HUD should be particularly

empowering.