Tuesday, September 04. 2012

The History of Sound Cards and Computer Game Music

Via MacGateway

-----

1981: PC Speaker

If you had an IBM PC computer or a 100-percent compatible clone between 1981-1988, you were most likely listening to — or cutting the wires of — your computer’s internal speaker. The PC speaker was solely a rudimentary tone generator. It played one note at a time, didn’t have different instruments for composers to choose from and even lacked volume control. As a result, music played on the PC speaker tended to sound tinny and grating. Composers could get around these problems by varying the pitch of a note slightly to create vibrato and playing fast arpeggios to simulate the sound of multiple notes being played simultaneously. By playing short “blips” between notes — short low-pitched sounds in the middle of a longer, high-pitched sound, for example — it was possible to simulate percussion. However, most PC speaker music didn’t have this much effort put into it; game music from this era often sounded rather monotonous. Through a clever hack, some computer games from the late ’80s actually played 6-bit digital sound through the PC speaker. However, this technology was used in few games because it was difficult to play digital sound through the speaker without sacrificing speed. When sound cards began to drop in price, the digital sound hack became irrelevant.

Listen to the PC Speaker

Composed by Nobuyuki Aoshima, Mecano Associates, Hibiki Godai, Fumihito Kasatani and Hiromi Ohba. Developed by Game Arts and published by Sierra On-Line.

This piece from the Silpheed soundtrack illustrates the technique most composers used when writing music for the PC speaker; the speaker plays the main melody only, and no tricks are used to simulate rhythm or accompaniment.

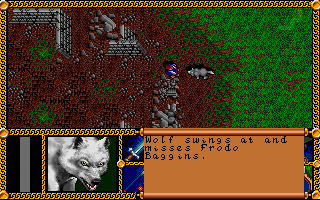

J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I (1990)

J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I (1990)

Composed by Charles Deenen and Kurt Heiden. Developed by Interplay and published by Electronic Arts.

By toggling rapidly between different notes, the theme from Interplay’s The Lord of the Rings creates the impression of up to four voices playing simultaneously from the PC speaker.

Composed by Michel Winogradoff. Developed and published by Loricels.

Hearing digital samples from an IBM-compatible computer before the release of the Sound Blaster was quite a novelty. Because of space limitations — Space Racer shipped on just one 5.25-inch floppy diskette — each sample is stored on the disk only once. The song is played by triggering the samples in a specific order.

Will Harvey’s Music Construction Set (1984)

Will Harvey’s Music Construction Set (1984)

Unknown composer. Developed and published by Electronic Arts.

Music Construction Set accomplished the seemingly impossible by playing four simultaneous voices with no audible toggling. Although the voices have a bit of a “fuzzy” quality, you can clearly hear the details of the composition.

Unknown composer. Developed by Byron Preiss Video Productions and published by Telarium.

While PCjr and Tandy 1000 owners were treated to a wonderful three-voice opening theme when playing Rendezvous With Rama, the PC speaker version of the theme switches confusingly from one “instrument” to another in an attempt to create the same effect.

1984: IBM PCjr and Tandy 1000

The

PCjr was released by IBM in 1984 as an attempt to provide better

competition for Apple in the home computer market. The PCjr included

features designed to appeal to home users, such as an infrared wireless

keyboard, cartridge slots and expansion hardware that could be installed

without opening the computer. More importantly, the PCjr featured

enhanced graphics and a sound chip that could play three voices

simultaneously rather than the one voice of the original IBM PC. IBM

contacted the game company Sierra On-Line, asking them to design a game

that would show off the enhanced graphics and sound of the PCjr. The

result was King’s Quest. The game became an enormous hit, saving Sierra from a failed investment in cartridge-based games just before the video game crash of 1983 and spawning a series that lasted 14 years.

The

PCjr was released by IBM in 1984 as an attempt to provide better

competition for Apple in the home computer market. The PCjr included

features designed to appeal to home users, such as an infrared wireless

keyboard, cartridge slots and expansion hardware that could be installed

without opening the computer. More importantly, the PCjr featured

enhanced graphics and a sound chip that could play three voices

simultaneously rather than the one voice of the original IBM PC. IBM

contacted the game company Sierra On-Line, asking them to design a game

that would show off the enhanced graphics and sound of the PCjr. The

result was King’s Quest. The game became an enormous hit, saving Sierra from a failed investment in cartridge-based games just before the video game crash of 1983 and spawning a series that lasted 14 years.

Some

of IBM’s design decisions for the PCjr were poor ones, and the computer

ultimately failed. However, Radio Shack’s Tandy 1000 — an

IBM-compatible computer with the same video and sound capabilities as

the PCjr — was a big seller. IBM still set the computing standard at

that point, and since the PCjr wasn’t a success, not all games took

advantage of the Tandy 1000?s advanced sound capabilities. Those that

did provided a significantly better audio experience on the Tandy 1000

than they did on the IBM PC.

Some

of IBM’s design decisions for the PCjr were poor ones, and the computer

ultimately failed. However, Radio Shack’s Tandy 1000 — an

IBM-compatible computer with the same video and sound capabilities as

the PCjr — was a big seller. IBM still set the computing standard at

that point, and since the PCjr wasn’t a success, not all games took

advantage of the Tandy 1000?s advanced sound capabilities. Those that

did provided a significantly better audio experience on the Tandy 1000

than they did on the IBM PC.

Listen to the Tandy 1000

Silpheed (1988)

Silpheed (1988)

Although the sound chip of the Tandy 1000 lacked an effects channel for percussion, the three-voice polyphony made it possible to construct a full piece of music with melody, harmony and bass. The Tandy 1000 version of the Silpheed soundtrack was a significant improvement over the PC speaker version.

Rendezvous With Rama (1984)

Rendezvous With Rama (1984)

The Tandy 1000 version of the introduction piece for Rendezvous With Rama conveys the full effect of what the composer intended, while the PC speaker version could only “fake” it by switching from voice to voice. Because the quality of PC game music was generally rather low in the early ’80s, hearing such a complex piece at the beginning of a game was a real treat.

Music Construction Set (1984)

Music Construction Set (1984)

The PC speaker version of Music Construction Set was done so well that the difference between it and the Tandy 1000 version isn’t quite “night and day” as it is with some other games. However, because the Tandy 1000 could play multiple voices without tricks, the tones do sound less “fuzzy.”

Composed by Hibiki Godai. Developed by Game Arts and published by Sierra On-Line.

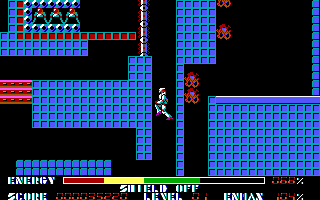

Thexder, the pinnacle of PC action gaming in 1987. features an appropriately energetic soundtrack that makes use of arpeggios to suggest chord changes. If the music sounds familiar to you, it may have something to do with the fact that Hibiki Godai also contributed to the Silpheed soundtrack.

1987: AdLib Music Synthesizer

A

few different sound cards were available to purchase in 1987, but few

people other than professional musicians were aware of them. Sierra

On-Line became a driving force in the evolution of computer sound again,

approaching AdLib and Roland about putting together bundles of their

products — the AdLib Music Synthesizer card and Roland MT-32 sound

module — for Sierra to market. Sierra then hired professional musicians

such as William Goldstein (Fame) and Bob Siebenberg (Supertramp) to compose soundtracks supporting these devices for their upcoming games. Sierra also mailed letters

and demonstration cassettes to its customers to promote the AdLib and

Roland MT-32, and the consumer sound card market was born.

A

few different sound cards were available to purchase in 1987, but few

people other than professional musicians were aware of them. Sierra

On-Line became a driving force in the evolution of computer sound again,

approaching AdLib and Roland about putting together bundles of their

products — the AdLib Music Synthesizer card and Roland MT-32 sound

module — for Sierra to market. Sierra then hired professional musicians

such as William Goldstein (Fame) and Bob Siebenberg (Supertramp) to compose soundtracks supporting these devices for their upcoming games. Sierra also mailed letters

and demonstration cassettes to its customers to promote the AdLib and

Roland MT-32, and the consumer sound card market was born.

Although the Roland MT-32 was a far better synthesizer, it was the AdLib Music Synthesizer card that would set the standard in PC audio for the next few years — mostly due to its lower price tag. The AdLib cost $200, making it far more affordable than the $550 MT-32 ($1,053 in 2012 dollars). The AdLib generated music with a Yamaha YM3812 chip, which produced sound through FM synthesis. The YM3812 was also known as the FM Operator Type-L 2 or OPL2 chip; it could play up to nine voices simultaneously and produced tones by manipulating waveforms such as sine and half-sine waves. The sound quality was not unlike that of the inexpensive Japanese keyboards that many families had stashed under their couches in the late ’80s. The AdLib lacked the ability to produce true stereo audio or play digital sound samples of any kind. Nevertheless, it could produce rich, full sounds in the hands of skilled composers, as demonstrated by some of the samples below. Its primary shortcoming stemmed from the fact that many game music composers focused most of their efforts on high-end MIDI hardware such as the Roland MT-32 and Sound Canvas SC-55. In converting these soundtracks for the AdLib, little time was spent tweaking the music to highlight the AdLib’s strengths. Some of the best AdLib music was composed by demoscene members and shareware game companies, perhaps because their smaller budgets made purchasing the expensive Roland hardware impossible.

Listen to the AdLib

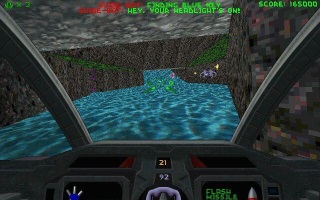

Silpheed (1988)

Silpheed (1988)

Although music produced by the AdLib may sound primitive by today’s standards, the AdLib version of the Silpheed soundtrack is a dramatic upgrade over the PC speaker version. This piece features percussion, synthesized brass, bass and bells.

The Alibi (1992)

The Alibi was originally composed for the Commodore 64 by Thomas E. Petersen (“Laxity”) and converted to the AdLib by Jens-Christian Huus (“LCH”). Both were members of the computer music group Vibrants. The Alibi features rich bass and makes full use of the AdLib’s capabilities. using techniques such as vibrato and ADSR envelopes for a more expressive sound.

Traffic Department 2192 (1994)

Traffic Department 2192 (1994)

Composed by Robert A. Allen and Owen Pallett. Developed by P Squared and published by Safari Software.

Traffic Department 2192 supported only PC speaker and AdLib/Sound Blaster sound, possibly because the composer didn’t have access to high-end MIDI hardware. As a result, the soundtrack is engaging and comes off sounding like it was composed for the device rather than converted from the original MT-32 version.

Composed by Stéphane Picq. Developed by Cryo Interactive and published by Virgin Games.

Although Dune supported the Roland MT-32 and LAPC-1, it is the AdLib version of the soundtrack that everyone remembers — perhaps because few people owned the expensive Roland hardware, but also, I think, because of the skillfulness with which the soundtrack was composed. An enhanced version of the soundtrack was released as the CD Dune: Spice Opera. Unfortunately, the CD is out of print and very difficult to find.

Composed by Mieko Ishikawa, Y?z? Koshiro, Hideaki Nagata, and Reiko Takebayashi. Developed by Nihon Falcom and published by Sierra On-Line.

Sorcerian was a lengthy game for its time, and it has a long, varied soundtrack to match. Unfortunately, the AdLib conversion of the soundtrack suffers a bit from a lack of bass and comes off sounding a little tinny.

1987: Roland MT-32

The

Roland MT-32 was a sound module that could be connected externally to a

computer via a MIDI interface card. It produced sound using a

combination of digital samples and subtractive waveform manipulation,

resulting in synthesized music that continues to sound quite

professional today. Roland later condensed the capabilities of the MT-32

into a computer expansion card called the LAPC-1. The LAPC-1 cost

slightly less than the MT-32 at $425, but it measured around 14 inches

in length and required a large computer chassis. The fact that the MT-32

could not play digital sound samples would become a limitation by the

early 1990s, but those who owned MT-32 experienced the best music that

computer games had to offer until pre-recorded digital sound became the

norm. The MT-32 could produce sound in true stereo, playing up to 32

voices simultaneously depending on the instruments selected. The string,

synthesizer and percussion sounds were particularly good for that era,

and the MT-32 even found its way into some mainstream music released

during the ’80s such as Pete Townshend’s song Man Machines.

The MT-32 also had a reverb effect, adding realism and depth to the

music. All sounds produced by the AdLib card were completely dry,

lacking environmental effects of any kind.

The

Roland MT-32 was a sound module that could be connected externally to a

computer via a MIDI interface card. It produced sound using a

combination of digital samples and subtractive waveform manipulation,

resulting in synthesized music that continues to sound quite

professional today. Roland later condensed the capabilities of the MT-32

into a computer expansion card called the LAPC-1. The LAPC-1 cost

slightly less than the MT-32 at $425, but it measured around 14 inches

in length and required a large computer chassis. The fact that the MT-32

could not play digital sound samples would become a limitation by the

early 1990s, but those who owned MT-32 experienced the best music that

computer games had to offer until pre-recorded digital sound became the

norm. The MT-32 could produce sound in true stereo, playing up to 32

voices simultaneously depending on the instruments selected. The string,

synthesizer and percussion sounds were particularly good for that era,

and the MT-32 even found its way into some mainstream music released

during the ’80s such as Pete Townshend’s song Man Machines.

The MT-32 also had a reverb effect, adding realism and depth to the

music. All sounds produced by the AdLib card were completely dry,

lacking environmental effects of any kind.

Listen to the Roland MT-32

Silpheed (1988)

Silpheed (1988)

The Silpheed theme was one of the pieces that Sierra used to hype the Roland MT-32, and it was an appropriate choice; the beginning highlights the MT-32?s excellent built-in digital reverb, and the main section of the piece features excellent synth and wind sounds as well as a driving percussion track. While this is a catchy piece on any sound card, it was obviously meant to be heard on the MT-32.

Composed by Nobuyuki Aoshima and Fumihito Kasatani. Developed by Game Arts and published by Sierra On-Line.

The Roland MT-32 has a display screen that shows when instruments and other parameters change. Developers sometimes made it display fun messages, such as “Thank you for playing.” You could watch it to gain insight into how game music composers worked. This theme from Zeliard frequently changes lead instruments to add interest and variety.

Composed by Chris Braymen. Developed and published by Sierra On-Line.

This lovely piece from Quest for Glory II again highlights the lifelike reverb of the MT-32, while adding a “human” element in the subtle tempo and volume changes of the plucked harp.

Ultima VI: The False Prophet (1990)

Ultima VI: The False Prophet (1990)

Composed by Kenneth W. Arnold. Developed and published by Origin.

Many of the pieces from Ultima VI are deceptively simple, featuring only a handful of different instruments. Nevertheless, this soundtrack has wiggled its way into the brain of many an Ultima fan and once it grabs hold, look out.

Sorcerian (1990)

Sorcerian (1990)

The synth-rock pieces in the Sorcerian soundtrack are some of the best that early ’90s computer games had to offer. On the MT-32, you can hear exactly what the soundtrack’s composers were going for: hard-driving drums, big synthesizer sounds and more than a little Duran Duran influence. In all, the Sorcerian soundtrack featured 59 distinct songs.

1988: Creative Music Systems Game Blaster

In

1987, Creative Music Systems released a sound card called the Creative

Music System or C/MS card, later re-releasing it through Radio Shack in

1988 as the Game Blaster. The Game Blaster could play up to 12 channels

of sound simultaneously in true stereo, with each channel playing a

square wave for melody or a noise for sound effects and percussion.

Because the square wave was the only non-percussion “instrument”

available. the Game Blaster was seen as vastly inferior to the AdLib. It

was similar in tonal quality to four Tandy 1000s playing

simultaneously, except for the fact that the Game Blaster had the

ability to adjust the volume of individual sound channels. The primary

companies that supported the Game Blaster were Sierra, Electronic Arts

and Accolade. Most other companies stayed away, and most consumers with

around $200 to spend on a sound card chose the AdLib. However, AdLib’s

superiority wouldn’t last much longer; in 1989, Creative Music Systems

rechristened itself Creative Labs and released the Sound Blaster.

In

1987, Creative Music Systems released a sound card called the Creative

Music System or C/MS card, later re-releasing it through Radio Shack in

1988 as the Game Blaster. The Game Blaster could play up to 12 channels

of sound simultaneously in true stereo, with each channel playing a

square wave for melody or a noise for sound effects and percussion.

Because the square wave was the only non-percussion “instrument”

available. the Game Blaster was seen as vastly inferior to the AdLib. It

was similar in tonal quality to four Tandy 1000s playing

simultaneously, except for the fact that the Game Blaster had the

ability to adjust the volume of individual sound channels. The primary

companies that supported the Game Blaster were Sierra, Electronic Arts

and Accolade. Most other companies stayed away, and most consumers with

around $200 to spend on a sound card chose the AdLib. However, AdLib’s

superiority wouldn’t last much longer; in 1989, Creative Music Systems

rechristened itself Creative Labs and released the Sound Blaster.

Listen to the Game Blaster

Silpheed (1988)

Silpheed (1988)

The Game Blaster version of the Silpheed soundtrack is a slight improvement over the Tandy 1000 version but pales in comparison to the AdLib and MT-32 versions. The lack of percussion hampers the Game Blaster, as does the fact that many soundtracks utilized the high end of its tonal range, which tended to sound tinny.

Composed by Herman Miller and Martin Galway. Developed and Published by Origin.

When composers utilized the low end of the Game Blaster’s range, they could create rich, full music that was every bit as compelling as AdLib music in its own way. Unfortunately, few composers did. Times of Lore is perhaps the most prominent exception.

Ultima VI (1990)

Ultima VI (1990)

While the Game Blaster version of the Ultima VI soundtrack stays within the Game Blaster’s lower register, it doesn’t play to the card’s strengths quite as well as the Times of Lore soundtrack did and pales in comparison to the MT-32 version. Because few people purchased Game Blaster cards, creating soundtracks that lived up to the card’s potential was rarely a priority.

Sorcerian (1990)

Sorcerian (1990)

The Game Blaster adaptation of the Sorcerian soundtrack fails to convey the synth-rock excitement of the original MT-32 version. By staying within the card’s high register, the music sounds thin and overly computerized.

1989: Creative Labs Sound Blaster

In

the history of the computer industry, many companies have designed

products using off-the-shelf components to save on development costs and

get something to the market as quickly as possible, only to be

outplayed later by clone manufacturers. The IBM PC is the most prominent

example, and the AdLib Music Synthesizer card is another. The AdLib

used the Yamaha YM3812 chip — which anyone could buy — to produce sound.

Because of the low price and the fact that it was one of the first

sound cards supported by computer games, the AdLib became the first de

facto standard for audio in IBM-compatible computers. Creative Music

Systems may have failed to set a new standard with the Game Blaster, but

the rechristened Creative Labs wouldn’t make the same mistake. The

Sound Blaster included the AdLib’s YM3812 chip, making it fully

compatible with the industry standard. However, it also had two highly

desirable features that the AdLib lacked: a game port and the ability to

record and play digital sounds. Although few games exploited the Sound

Blaster’s ability to play digital samples when it was first released,

the game port was a strong selling point because it allowed a computer

to support a joystick. Because game cards cost around $50 at the time, a

consumer could spend less — and get more — by buying the Sound Blaster

rather than the AdLib and a separate game card. Sound Blaster became the

new standard for computer audio, and although AdLib’s follow-up — the

AdLib Gold — was superior, AdLib lacked Creative Labs’ marketing skills

and was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1992.

In

the history of the computer industry, many companies have designed

products using off-the-shelf components to save on development costs and

get something to the market as quickly as possible, only to be

outplayed later by clone manufacturers. The IBM PC is the most prominent

example, and the AdLib Music Synthesizer card is another. The AdLib

used the Yamaha YM3812 chip — which anyone could buy — to produce sound.

Because of the low price and the fact that it was one of the first

sound cards supported by computer games, the AdLib became the first de

facto standard for audio in IBM-compatible computers. Creative Music

Systems may have failed to set a new standard with the Game Blaster, but

the rechristened Creative Labs wouldn’t make the same mistake. The

Sound Blaster included the AdLib’s YM3812 chip, making it fully

compatible with the industry standard. However, it also had two highly

desirable features that the AdLib lacked: a game port and the ability to

record and play digital sounds. Although few games exploited the Sound

Blaster’s ability to play digital samples when it was first released,

the game port was a strong selling point because it allowed a computer

to support a joystick. Because game cards cost around $50 at the time, a

consumer could spend less — and get more — by buying the Sound Blaster

rather than the AdLib and a separate game card. Sound Blaster became the

new standard for computer audio, and although AdLib’s follow-up — the

AdLib Gold — was superior, AdLib lacked Creative Labs’ marketing skills

and was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1992.

The first Sound Blaster included a chip that made it backwards-compatible with the Game Blaster. It could play 8-bit, 23 kHz audio and record 8-bit, 12 kHz audio, both in single-channel mono. Although this was significantly lower than CD quality, it worked well for sound effects in games. Prior to the release of the Sound Blaster, many games with AdLib support used the AdLib for music while playing sound effects through the PC speaker. The Sound Blaster provided a much better experience when its ability to play digital sounds was utilized. Unfortunately, the Sound Blaster could also be a bit buggy. It required manual IRQ configuration and frequently conflicted with other hardware in the computer. Digital sounds were preceded by loud pops and sometimes caused computers to lock up.

Listen to the Sound Blaster

Composed by Daniel Gardopee, Andrew G. Sega and Straylight Productions. Developed by Origin and published by Electronic Arts.

This piece from the Crusader installation program illustrates the Sound Blaster’s ability to play music based on digital samples. Although the Sound Blaster is limited to 8-bit mono sounds, the Crusader soundtrack sounds far better than most games that utilized the YM3812 chip. The AdLib could not have reproduced this soundtrack at all.

Composed by Ken Allen, Brian Luzietti, Larry Peacock, Leslie Spitzer, Jim Torres and Tim Wiles. Developed by Parallax Software and published by Interplay.

Descent was one of the few games with separate soundtracks for the Sound Blaster and Sound Blaster 16. This OPL2 version of the soundtrack utilizes the YM3812 chip, which means that it would sound exactly the same on the AdLib.

Composed by Johann Langlie, Brian Luzietti, Mark Morgan, Larry Peacock, Peter Rotter and Leslie Spitzer. Developed by Parallax Software and published by Interplay.

Although this piece from Descent II is more mature and complex than the selection from the first game, it seems to overpower the YM3812 at one point. Near the end of the piece, instruments begin to cut out, perhaps because the maximum polyphony of the Sound Blaster has been reached.

1991: Roland Sound Canvas SC-55

MIDI

— the Musical Instrument Digital Interface — was invented around 1982

as a means of communicating with electronic musical instruments. MIDI

allowed a musician with one keyboard to expand his available instrument

sounds by connecting sound modules such as the Roland MT-32. The

keyboard sent commands containing parameters such as the instrument

number and the pitch, volume and duration of the note, and the sound

module played the requested sound. MIDI also enabled computers to

interface with electronic instruments, making it possible for the MT-32

to play game soundtracks. Before 1991, however, MIDI had a serious

problem: there was no standard for instrument numbers. Instrument 001

might be an acoustic grand piano on one synthesizer and an electric

guitar on another, so to get the correct sound, you needed to play a

piece of music using the synthesizer on which it was composed. General

MIDI changed that by creating a standard list of 128 instrument numbers.

Synthesizers could contain additional instruments and features if the

manufacturer implemented them, but had to contain the basic list of 128

to be GM-compatible.

MIDI

— the Musical Instrument Digital Interface — was invented around 1982

as a means of communicating with electronic musical instruments. MIDI

allowed a musician with one keyboard to expand his available instrument

sounds by connecting sound modules such as the Roland MT-32. The

keyboard sent commands containing parameters such as the instrument

number and the pitch, volume and duration of the note, and the sound

module played the requested sound. MIDI also enabled computers to

interface with electronic instruments, making it possible for the MT-32

to play game soundtracks. Before 1991, however, MIDI had a serious

problem: there was no standard for instrument numbers. Instrument 001

might be an acoustic grand piano on one synthesizer and an electric

guitar on another, so to get the correct sound, you needed to play a

piece of music using the synthesizer on which it was composed. General

MIDI changed that by creating a standard list of 128 instrument numbers.

Synthesizers could contain additional instruments and features if the

manufacturer implemented them, but had to contain the basic list of 128

to be GM-compatible.

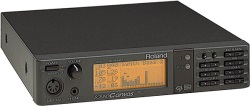

The Sound Canvas SC-55 was Roland’s first GM-compatible sound module. It became the preferred sound device for games with General MIDI soundtracks, both because of its exceptional sound quality and because many composers used it to create game soundtracks. Although the GM standard defined the basic list of 128 instruments, manufacturers used their own samples and synthesizer chips to create them. This resulted in slight variances in instrument balance and tonal quality between different devices, even when playing the same MIDI composition. Therefore, the only way to hear many game soundtracks exactly they were composed was to play them on the SC-55.

Although the Sound Canvas SC-55 was one of the best MIDI synthesizers on the market in 1991, it saw limited success among non-musicians because gamers had begun to demand digital sound playback and Sound Blaster compatibility. A computer owner could experience the best that modern games had to offer by using a Sound Canvas SC-55 for MIDI music and a Sound Blaster for sound effects, but few people had upwards of $1,000 to spend on hardware for game music. The Sound Canvas line became a successful one for Roland; descendants of the SC-55 remain available today.

Listen to the Roland Sound Canvas SC-55

Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers (1993)

Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers (1993)

Composed by Robert Holmes. Developed and published by Sierra On-Line.

The SC-55 soundtrack for Sierra’s first entry in the Gabriel Knight series, with classical, jazz and rock influences, shows the full range of the sound module’s capabilities. Pay particular attention to the swell of the piano, organ and chorus about two thirds into the first piece.

Quest for Glory IV: Shadows of Darkness (1993)

Quest for Glory IV: Shadows of Darkness (1993)

Composed by Aubrey Hodges. Developed and published by Sierra On-Line.

In addition to a much better acoustic grand piano, the SC-55 featured guitar sounds that were vastly superior to those on the MT-32. The Quest for Glory IV soundtrack features heavy use of the electric guitar sound and utilizes real playing techniques such as bends, tremolo picking and hammer-ons.

1992: Gravis UltraSound

There

are many who believe that Gravis is the company that should have won

the sound card wars in the early ’90s. During this time, Creative Labs

dragged their heels a bit, improving the Sound Blaster slowly because no

other company posed any real competition. During this time, Creative’s

flagship product was the Sound Blaster Pro, which featured two

Yamaha YM3812 chips for stereo music and had the ability to record

stereo sounds up to 22.05 kHz and mono sounds up to 44.1 kHz. However,

the sample size was still limited to 8 bits. The Gravis Ultrasound

represented a major step forward; out of the box, it could play 16-bit

sounds and record 8-bit sounds with a maximum sample rate of 44.1 kHz.

It was also possible to upgrade the Ultrasound with an add-on board that

allowed it to record 16-bit sounds in full CD quality.

There

are many who believe that Gravis is the company that should have won

the sound card wars in the early ’90s. During this time, Creative Labs

dragged their heels a bit, improving the Sound Blaster slowly because no

other company posed any real competition. During this time, Creative’s

flagship product was the Sound Blaster Pro, which featured two

Yamaha YM3812 chips for stereo music and had the ability to record

stereo sounds up to 22.05 kHz and mono sounds up to 44.1 kHz. However,

the sample size was still limited to 8 bits. The Gravis Ultrasound

represented a major step forward; out of the box, it could play 16-bit

sounds and record 8-bit sounds with a maximum sample rate of 44.1 kHz.

It was also possible to upgrade the Ultrasound with an add-on board that

allowed it to record 16-bit sounds in full CD quality.

The music synthesizer component of the Ultrasound was also miles ahead of the Sound Blaster Pro. The Ultrasound came with 256 KB of built-in sample memory and supported a maximum of 1 MB. Using this sample memory, composers and game programmers could create “tracker music” — constructed by manipulating digital samples rather than sending commands to a hardware synthesizer — using samples stored entirely in the sound card’s memory. In addition, the Ultrasound featured a hardware mixer that could independently adjust the volume of each voice before sending it to the computer’s speakers. The Sound Blaster Pro also supported tracked music, but it had no built-in memory and relied on the computer’s processor to mix multiple voices. During a time when a typical computer had a 386 or 486 processor and 4-8 MB of RAM, allocating 256 KB of system memory to audio samples and using the processor to mix voices resulted in a significant drain on system resources. Games utilizing the Ultrasound had better sound quality and smoother animation.

However, the Gravis Ultrasound had trouble gaining acceptance among consumers who weren’t hardcore gamers, musicians or demoscene members because it lacked the Yamaha YM3812 chip and therefore wasn’t completely Sound Blaster-compatible. By this time, Creative Labs had been successful in creating an industry standard that consumers looked for when buying sound cards. My research suggests that Gravis announced the Ultrasound in 1991, but didn’t release it until October 1992. This gave Creative plenty of time to prepare a counter-attack, resulting in the release of the Sound Blaster 16 in June 1992.

Listen to the Gravis Ultrasound

Descent (1995)

Descent (1995)

It could sometimes be difficult to find games with proper support for the Gravis UltraSound

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (130837)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101434)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (99851)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57663)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57232)