Monday, October 08. 2012

There Really Is a Smartphone Inside ‘EW Magazine’

Via Mashable

-----

They told us, but we did not believe them: The Oct. 5 print edition of Entertainment Weekly, which features a one-of-a-kind digital ad running video and live tweets, actually has a smartphone inside of it. A real, full-sized 3G cellphone inside a print magazine.

The digital ad is designed to promote the CW network’s fresh lineup of action shows (The Arrow and Emily Owens, M.D.) and, when you open the magazine to the ad, the small LCD screen shows short clips of the two shows and then switches to live tweets from CW’s Twitter account.

When we spoke to CW representatives earlier this week, they did tell us that “the ad is powered by a custom-built, smartphone-like Android device with an LED screen and 3G connectivity; it was manufactured in China.” This is all true, though the device is far more than just “smartphone-like.”

During our teardown, we discovered a smartphone-sized battery, a full QWERTY keyboard hidden under black plastic tape, a T-Mobile 3G card, a camera, speaker and a live USB port that will accept a mini USB cable, which you can then plug into a computer and recharge the phone. We could also see from the motherboard that the smartphone was built by Foxconn. You may have heard of it.

Once we extracted the phone from its clear plastic housing (which was sandwiched between two rather thick card-stock pages), we were able to use a screw driver to close the open contacts on the touch pad and access the on-screen Android menu, which has a full complement of apps. It wasn’t easy, but we even made a phone call.

That’s right, there’s nothing wrong with this phone, other than it being old, under powered and partially in Chinese. Oh, yes, and the fact that it’s jammed inside a print magazine.

Mashable Senior Tech Analyst Christina Warren, who assisted in our teardown, did some research (including using the number on the motherboard) and is now fairly certain that guts come from this $86 ABO smartphone. Don’t worry, it’s unlikely that it cost the CW anywhere near that much.

Entertainment Weekly is only producing 1,000 of these digital advertising-enhanced issues, so if you want a nearly free smartphone that, with a good deal of nudging, actually works, you better run, not walk, to your nearest newsstand.

In the meantime, we’ll keep playing with the phone to see if we can make it perform other tricks, like calling the phone number we desire and crafting our own tweets. We did finally get the camera working, but without a lens over it, the images are a blurry mess. More challenges for what I’m officially naming our Entertainment Weekly Digital Ad/Smartphone Print Insert Hackathon!

Thursday, October 04. 2012

How Google Builds Its Maps—and What It Means for the Future of Everything

Via The Atlantic

-----

Behind every Google Map, there is a much more complex map that's the key to your queries but hidden from your view. The deep map contains the logic of places: their no-left-turns and freeway on-ramps, speed limits and traffic conditions. This is the data that you're drawing from when you ask Google to navigate you from point A to point B -- and last week, Google showed me the internal map and demonstrated how it was built. It's the first time the company has let anyone watch how the project it calls GT, or "Ground Truth," actually works.

Google opened up at a key moment in its evolution. The company began as an online search company that made money almost exclusively from selling ads based on what you were querying for. But then the mobile world exploded. Where you're searching from has become almost as important as what you're searching for. Google responded by creating an operating system, brand, and ecosystem in Android that has become the only significant rival to Apple's iOS.

And for good reason. If Google's mission is to organize all the world's information, the most important challenge -- far larger than indexing the web -- is to take the world's physical information and make it accessible and useful.

"If you look at the offline world, the real world in which we live, that information is not entirely online," Manik Gupta, the senior product manager for Google Maps, told me. "Increasingly as we go about our lives, we are trying to bridge that gap between what we see in the real world and [the online world], and Maps really plays that part."

This is not just a theoretical concern. Mapping systems matter on phones precisely because they are the interface between the offline and online worlds. If you're at all like me, you use mapping more than any other application except for the communications suite (phone, email, social networks, and text messaging).

Google is locked in a battle with the world's largest company, Apple, about who will control the future of mobile phones. Whereas Apple's strengths are in product design, supply chain management, and retail marketing, Google's most obvious realm of competitive advantage is in information. Geo data -- and the apps built to use it -- are where Google can win just by being Google. That didn't matter on previous generations of iPhones because they used Google Maps, but now Apple's created its own service. How the two operating systems incorporate geo data and present it to users could become a key battleground in the phone wars.

But that would entail actually building a better map.

***

The office where Google has been building the best representation of the world is not a remarkable place. It has all the free food, ping pong, and Google Maps-inspired Christoph Niemann cartoons that you'd expect, but it's still a low-slung office building just off the 101 in Mountain View in the burbs.

I was slated to meet with Gupta and the engineering ringleader on his team, former NASA engineer Michael Weiss-Malik, who'd spent his 20 percent time working on Google Mars, and Nick Volmar, an "operator" who actually massages map data.

"So you want to make a map," Weiss-Malik tells me as we sit down in front of a massive monitor. "There are a couple of steps. You acquire data through partners. You do a bunch of engineering on that data to get it into the right format and conflate it with other sources of data, and then you do a bunch of operations, which is what this tool is about, to hand massage the data. And out the other end pops something that is higher quality than the sum of its parts."

This is what they started out with, the TIGER data from the US Census Bureau (though the base layer could and does come from a variety of sources in different countries).

On first inspection, this data looks great. The roads look like they are all there and you've got the freeways differentiated. This is a good map to the untrained eye. But let's look closer. There are issues where the digital data does not match the physical world. I've circled a few obvious ones below.

Later in the day, Google Maps VP Brian McClendon put it like this: "We can actually organize the world's physical written information if we can OCR it and place it," McClendon said. "We use that to create our maps right now by extracting street names and addresses, but there is a lot more there."

More like what? "We already have what we call 'view codes' for 6 million businesses and 20 million addresses, where we know exactly what we're looking at," McClendon continued. "We're able to use logo matching and find out where are the Kentucky Fried Chicken signs ... We're able to identify and make a semantic understanding of all the pixels we've acquired. That's fundamental to what we do."

For now, though, computer vision transforming Street View images directly into geo-understanding remains in the future. The best way to figure out if you can make a left turn at a particular intersection is still to have a person look at a sign -- whether that's a human driving or a human looking at an image generated by a Street View car.

There is an analogy to be made to one of Google's other impressive projects: Google Translate. What looks like machine intelligence is actually only a recombination of human intelligence. Translate relies on massive bodies of text that have been translated into different languages by humans; it then is able to extract words and phrases that match up. The algorithms are not actually that complex, but they work because of the massive amounts of data (i.e. human intelligence) that go into the task on the front end.

Google Maps has executed a similar operation. Humans are coding every bit of the logic of the road onto a representation of the world so that computers can simply duplicate (infinitely, instantly) the judgments that a person already made.

This reality is incarnated in Nick Volmar, the operator who has been showing off Atlas while Weiss-Malik and Gupta explain it. He probably uses twenty-five keyboard shortcuts switching between types of data on the map and he shows the kind of twitchy speed that I associate with long-time designers working with Adobe products or professional Starcraft players. Volmar has clearly spent thousands of hours working with this data. Weiss-Malik told me that it takes hundreds of operators to map a country. (Rumor has it many of these people work in the Bangalore office, out of which Gupta was promoted.)

The sheer amount of human effort that goes into Google's maps is just mind-boggling. Every road that you see slightly askew in the top image has been hand-massaged by a human. The most telling moment for me came when we looked at couple of the several thousand user reports of problems with Google Maps that come in every day. The Geo team tries to address the majority of fixable problems within minutes. One complaint reported that Google did not show a new roundabout that had been built in a rural part of the country. The satellite imagery did not show the change, but a Street View car had recently driven down the street and its tracks showed the new road perfectly.

Volmar began to fix the map, quickly drawing the new road and connecting it to the existing infrastructure. In his haste (and perhaps with the added pressure of three people watching his every move), he did not draw a perfect circle of points. Weiss-Malik and I detoured into another conversation for a couple of minutes. By the time I looked back at the screen, Volmar had redrawn the circle with perfect precision and upgraded a few other things while he was at it. The actions were impressively automatic. This is an operation that promotes perfectionism.

And that's how you get your maps to look this this:

***

It's probably better not to think of Google Maps as a thing like a paper map. Geographic information systems represent a jump from paper maps like the abacus to the computer. "I honestly think we're seeing a more profound change, for map-making, than the switch from manuscript to print in the Renaissance," University of London cartographic historian Jerry Brotton told the Sydney Morning Herald. "That was huge. But this is bigger."

The maps we used to keep folded in our glove compartments were a collection of lines and shapes that we overlaid with human intelligence. Now, as we've seen, a map is a collection of lines and shapes with Nick Volmar's (and hundreds of others') intelligence encoded within.

It's common when we discuss the future of maps to reference the Borgesian dream of a 1:1 map of the entire world. It seems like a ridiculous notion that we would need a complete representation of the world when we already have the world itself. But to take scholar Nathan Jurgenson's conception of augmented reality seriously, we would have to believe that every physical space is, in his words, "interpenetrated" with information. All physical spaces already are also informational spaces. We humans all hold a Borgesian map in our heads of the places we know and we use it to navigate and compute physical space. Google's strategy is to bring all our mental maps together and process them into accessible, useful forms.

Their MapMaker product makes that ambition clear. Project managed by Gupta during his time in India, it's the "bottom up" version of Ground Truth. It's a publicly accessible way to edit Google Maps by adding landmarks and data about your piece of the world. It's a way of sucking data out of human brains and onto the Internet. And it's a lot like Google's open competitor, Open Street Map, which has proven that it, too, can harness the crowd's intelligence.

As we slip and slide into a world where our augmented reality is increasingly visible to us off and online, Google's geographic data may become its most valuable asset. Not solely because of this data alone, but because location data makes everything else Google does and knows more valuable.

Or as my friend and sci-fi novelist Robin Sloan put it to me, "I maintain that this is Google's core asset. In 50 years, Google will be the self-driving car company (powered by this deep map of the world) and, oh, P.S. they still have a search engine somewhere."

Of course, they will always need one more piece of geographic information to make all this effort worthwhile: You. Where you are, that is. Your location is the current that makes Google's giant geodata machine run. They've built this whole playground as an elaborate lure for you. As good and smart and useful as it is, good luck resisting taking the bait.Wednesday, October 03. 2012

Oculus Rift: VR gaming headset takes to Kickstarter

Via Edge

-----

UPDATE: Oculus Rift is not, as reported below, John Carmack's creation. The Id co-founder tweeted last night to confirm that "I have no direct ties with Oculus; I endorse it is a wonderful advance in VR tech, but I'm not "backing it".

The virtual reality headset John Carmack was showing off at E3 is now on Kickstarter. Named Oculus Rift, it has already raised three times its $250,000 goal since the project went live yesterday.

The project pitches Oculus Rift as the first truly functional and affordable VR headset, which "takes 3D gaming to the next level." The headset "is designed to maximise immersion, comfort, and pure, uninhibited fun, at a price everyone can afford."

Given Carmack's involvement it's little surprise that the project has, at the time of writing, raised $777,130 from over 3,000 backers. Some of the most respected people in the industry have also thrown their weight behind Oculus Rift, including Gabe Newell, who in a quote on the project page is full of praise for Oculus founder Palmer Luckey.

"It looks incredibly exciting," The Valve president says. "If anybody's going to tackle this set of hard problems, we think that Palmer's going to do it. So we'd strongly encourage you to support this Kickstarter."

Also on board are Epic Games design director Cliff Bleszinski ("I'm a believer"), Unity Technologies CEO David Helgason ("This will be the coolest way to experience games in the future"), and Michael Abrash, former colleague of Carmack at Id and now one of Valve's more prominent thinkers, who recently revealed the company's work on wearable computing.

Oculus Rift will be bundled with a copy of Doom 3 BFG, Id's revamp of its 2004 shooter and the first Rift-compatible game. Kickstarter reward tiers begin at $10, though the serious stuff is reserved for those pledging larger amounts. $275 will net you an unassembled Rift prototype; $300 gets you early access to the developer kit. The SDK is a work in progress, but Oculus plans on integration of Unreal Engine and Unity, opening up a host of possible platforms including PC and mobile.

Those paying $5,000 or more – three people have done so already – get all rewards plus a visit to the Oculus lab. One of the three is Markus "Notch" Persson, who tweeted last night to reveal he had pledged $10,000 and that there was a good chance Mojang's games would be supported – and let's be honest, a headset-controlled Minecraft is quite the prospect.

It's a remarkable turn of events coming just months after the headset's E3 debut. Carmack admitted the prototype was "literally held together with duct tape" and it certainly didn't seem like it was mere months away from becoming a serious proposition.

For more, we recommend PC Gamer's video of John Carmack's VR headset. David Boddington played Doom 3 BFG using the device, and came away resoundingly impressed, describing it as "unlike any other gaming experience I've had".

Tuesday, October 02. 2012

Questions abound as malicious phpMyAdmin backdoor found on SourceForge site

Via ars technica

-----

Developers of phpMyAdmin warned users they may be running a malicious version of the open-source software package after discovering backdoor code was snuck into a package being distributed over the widely used SourceForge repository.

The backdoor contains code that allows remote attackers to take control of the underlying server running the modified phpMyAdmin, which is a Web-based tool for managing MySQL databases. The PHP script is found in a file named server_sync.php, and it reads PHP code embedded in standard POST Web requests and then executes it. That allows anyone who knows the backdoor is present to execute code of his choice. HD Moore, CSO of Rapid7 and chief architect of the Metasploit exploit package for penetration testers and hackers, told Ars a module has already been added that tests for the vulnerability.

The backdoor is concerning because it was distributed on one of the official mirrors for SourceForge, which hosts more than 324,000 open-source projects, serves more than 46 million consumers, and handles more than four million downloads each day. SourceForge officials are still investigating the breach, so crucial questions remain unanswered. It's still unclear, for instance, if the compromised server hosted other maliciously modified software packages, if other official SourceForge mirror sites were also affected, and if the central repository that feeds these mirror sites might also have been attacked.

"If that one mirror was compromised, nearly every SourceForge package on that mirror could have been backdoored, too," Moore said. "So you're looking at not just phpMyAdmin, but 12,000 other projects. If that one mirror was compromised and other projects were modified this isn't just 1,000 people. This is up to a couple hundred thousand."

An advisory posted Tuesday on phpMyAdmin said: "One of the SourceForge.net mirrors, namely cdnetworks-kr-1, was being used to distribute a modified archive of phpMyAdmin, which includes a backdoor. This backdoor is located in file server_sync.php and allows an attacker to remotely execute PHP code. Another file, js/cross_framing_protection.js, has also been modified." phpMyAdmin officials didn't respond to e-mails seeking to learn how long the backdoored version had been available and how many people have downloaded it.

Update: In a blog post, SourceForge officials said they believe only the affected phpMyAdmin-3.5.2.2-all-languages.zip package was the only modified file on the cdnetworks mirror site, but they are continuing to investigate to make sure. Logs indicate that about 400 people downloaded the malicious package. The provider of the Korea-based mirror has confirmed the breach, which is believe to have happened around September 22, and indicated it was limited to that single mirror site. The machine has been taken out of rotation.

"Downloaders are at risk only if a corrupt copy of this software was obtained, installed on a server, and serving was enabled," the SourceForge post said. "Examination of web logs and other server data should help confirm whether this backdoor was accessed."

It's not the first time a widely used open-source project has been hit by a breach affecting the security of its many downstream users. In June of last year, WordPress required all account holders on WordPress.org to change their passwords following the discovery that hackers contaminated it with malicious software. Three months earlier, maintainers of the PHP programming language spent several days scouring their source code for malicious modifications after discovering the security of one of their servers had been breached.

A three-day security breach in 2010 on ProFTP caused users who downloaded the package during that time to be infected with a malicious backdoor. The main source-code repository for the Free Software Foundation was briefly shuttered that same year following the discovery of an attack that compromised some of the website's account passwords and may have allowed unfettered administrative access. And last August, multiple servers used to maintain and distribute the Linux operating system were infected with malware that gained root system access, although maintainers said the repository was unaffected.

Monday, October 01. 2012

HP launches Open webOS 1.0

Via SlashGear

-----

HP‘s TouchPad and Palm devices may be long and gone, but webOS (the mobile OS that these devices ran off of) has been alive and well despite its hardware extinction, mostly thanks to its open-source status. Open webOS, as its now called, went into beta in August, and now a month later, a final stable build is ready for consumption as version 1.0.

The 1.0 release offers some changes that the Open webOS team hopes will offer major new capabilities for developers. The team also mentions that over 75 Open webOS components have been delivered over the past 9 months (totaling over 450,000 lines of code), which means that Open webOS can now be ported to new devices thanks to today’s 1.0 release.

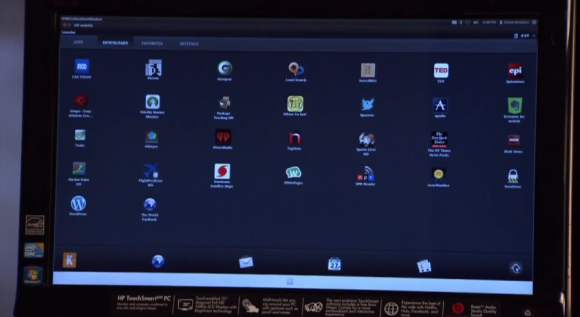

In the video below, Open webOS architect Steve Winston demoes the operating system on a HP TouchSmart all-in-one PC. He mentions that it took the team just “a couple of days” to port Open webOS to the PC that he has in front of him. The user interface doesn’t seem to be performing super smoothly, but you can’t really expect more out of a 1.0 release.

Winston says that possible uses for Open webOS include kiosk applications in places like hotels, and since Open webOS is aimed to work on phones, tablets, and PCs, there’s the possibility that Open webOS could become an all-in-one solution for kiosk or customer service platforms for businesses. Obviously, version 1.0 is just the first step, so the Open webOS team is just getting started with this project and they expect to only improve on it and add new features as time goes on.

Watch 32 discordant metronomes achieve synchrony in a matter of minutes

Via io9

-----

If you place 32 metronomes on a static object and set them rocking out of phase with one another, they will remain that way indefinitely. Place them on a moveable surface, however, and something very interesting (and very mesmerizing) happens.

The metronomes in this video fall into the latter camp. Energy from the motion of one ticking metronome can affect the motion of every metronome around it, while the motion of every other metronome affects the motion of our original metronome right back. All this inter-metranome "communication" is facilitated by the board, which serves as an energetic intermediary between all the metronomes that rest upon its surface. The metronomes in this video (which are really just pendulums, or, if you want to get really technical, oscillators) are said to be "coupled."

The math and physics surrounding coupled oscillators are actually relevant to a variety of scientific phenomena, including the transfer of sound and thermal conductivity. For a much more detailed explanation of how this works, and how to try it for yourself, check out this excellent video by condensed matter physicist Adam Milcovich.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131044)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101656)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100056)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57885)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57445)