Friday, April 19. 2013

A new way to report data center's Power and Water Usage Effectiveness (PUE and WUE)

-----

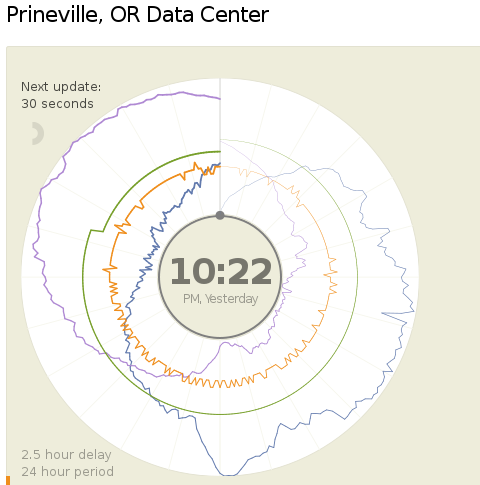

Today (18.04.2013) Facebook launched two public dashboards that report continuous, near-real-time data for key efficiency metrics – specifically, PUE and WUE – for our data centers in Prineville, OR and Forest City, NC. These dashboards include both a granular look at the past 24 hours of data and a historical view of the past year’s values. In the historical view, trends within each data set and correlations between different metrics become visible. Once our data center in Luleå, Sweden, comes online, we’ll begin publishing for that site as well.

We began sharing PUE for our Prineville data center at the end of Q2 2011 and released our first Prineville WUE in the summer of 2012. Now we’re pulling back the curtain to share some of the same information that our data center technicians view every day. We’ll continue updating our annualized averages as we have in the past, and you’ll be able to find them on the Prineville and Forest City dashboards, right below the real-time data.

Why are we doing this? Well, we’re proud of our data center efficiency, and we think it’s important to demystify data centers and share more about what our operations really look like. Through the Open Compute Project (OCP), we’ve shared the building and hardware designs for our data centers. These dashboards are the natural next step, since they answer the question, “What really happens when those servers are installed and the power’s turned on?”

Creating these dashboards wasn’t a straightforward task. Our data centers aren’t completed yet; we’re still in the process of building out suites and finalizing the parameters for our building managements systems. All our data centers are literally still construction sites, with new data halls coming online at different points throughout the year. Since we’ve created dashboards that visualize an environment with so many shifting variables, you’ll probably see some weird numbers from time to time. That’s OK. These dashboards are about surfacing raw data – and sometimes, raw data looks messy. But we believe in iteration, in getting projects out the door and improving them over time. So we welcome you behind the curtain, wonky numbers and all. As our data centers near completion and our load evens out, we expect these inevitable fluctuations to correspondingly decrease.

We’re excited about sharing this data, and we encourage others to do the same. Working together with AREA 17, the company that designed these visualizations, we’ve decided to open-source the front-end code for these dashboards so that any organization interested in sharing PUE, WUE, temperature, and humidity at its data center sites can use these dashboards to get started. Sometime in the coming weeks we’ll publish the code on the Open Compute Project’s GitHub repository. All you have to do is connect your own CSV files to get started. And in the spirit of all other technologies shared via OCP, we encourage you to poke through the code and make updates to it. Do you have an idea to make these visuals even more compelling? Great! We encourage you to treat this as a starting point and use these dashboards to make everyone’s ability to share this data even more interesting and robust.

Lyrica McTiernan is a program manager for Facebook’s sustainability team.

Wednesday, April 17. 2013

Google Mirror API now available

Tuesday, April 16. 2013

Oculus Rift finally gets the reaction virtual reality always wanted

Via Slash Gear

-----

We’ve already heard plenty about the Oculus Rift virtual reality headset, and while we youngsters are pretty amazed by the technology, nobody has their mind blown more than the elderly, who could only dream about such technology back in their younger days. Recently, a 90-year-old grandmother ended up trying out the Oculus Rift for herself, and she was quite amazed.

Imagimind Studio developer Paul Rivot ended up grabbing an Oculus Rift in order to play around with it and develop some games, but he took a break from that and decided to give his grandmother a little treat, by strapping the Oculus Rift to her head in order to experience a bit of virtual reality herself.

The video is quite entertaining to watch, and we can’t imagine what’s going on inside of her head, knowing that she never grew up with such technology as the Oculus Rift, let alone 3D video games. She even gets to the point where she thought the images being displayed were actual images taken on-location, when in fact it’s all 3D-rendered on a computer.

Currently, the Oculus Rift is out in the wild for developers only at this point, and there’s no announced release date for the device, although the company has noted that it should arrive to the general public before the 2014 holiday season. In the meantime, it’s videos like this that only excite us even more.

Tuesday, April 09. 2013

A Problem Google Has Created for Itself

Via The Atlantic

-----

Over the eons I've been a fan of, and sucker for, each latest automated system to "simplify" and "bring order to" my life. Very early on this led me to the beautiful-and-doomed Lotus Agenda for my DOS computers, and Actioneer for the early Palm. For the last few years Evernote has been my favorite, and I really like it. Still I always have the roving eye.

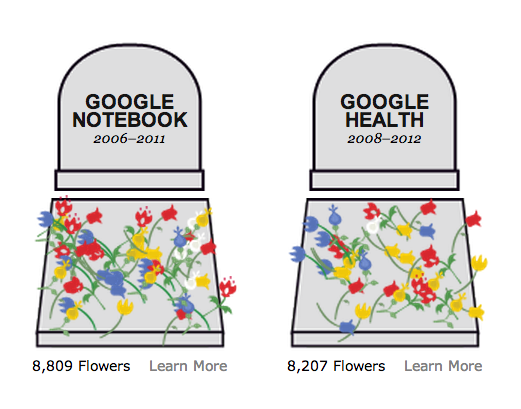

So naturally I have already downloaded the Android version of Google's new app for collecting notes, photos, and info, called Google Keep, with logo at right. This early version has nothing like Evernote's power or polish, but you can see where Google is headed.

Thursday, April 04. 2013

Writing Open Source Software? Make Sure You Know Your Copyright Rights

Via SmartBear

-----

Open source is all fine and dandy, but before throwing yourself – and untold lines of code – into a project, make sure you understand exactly what’s going to happen to your code’s copyrights. And to your career.

I know. If you wanted to be a lawyer, you would have gone to law school instead of spending your nights poring over K&R. Tough. In 2013, if you're an open source programmer you need to know a few things about copyright law. If you don't, bad things can happen. Really bad things.

Before launching into this topic, I must point out that I Am Not A Lawyer (IANAL). If you have a specific, real-world question, talk to someone who is a lawyer. Better still, talk to an attorney who specializes in intellectual property (IP) law.

Every time you write code, you're creating copyrighted work. As Simon Phipps, President of the OSI Open Source Initiative (OSI) said when I asked him about programmer copyright gotchas, "The biggest one is the tendency for headstrong younger developers to shun copyright licensing altogether. When they do that, they put all their collaborators at risk and themselves face potential liability claims.”

Developers need to know that copyright is automatic under the Berne Convention, Phipps explained. Since that convention was put into place, all software development involve copying and derivatives, Phipps said; all programming without a license potentially infringes on copyright. “It may not pose a problem today, but without a perpetual copyright license collaborators are permanently at risk."

“You can pretend copyright doesn't exist all you want, but one day it will bite you,” Phipps continued. “That's why [if you want to start a new project] you need to apply an open source license.” If you want public domain, use the MIT license; it's very simple and protects you and your collaborators from these risks. If you really care, use a modern patent-protecting license like Apache, MPLv2, or GPLv3. Just make sure you get one.

Who Owns That Work-for-Hire Code? It Might Be You

You should know when you own the copyright and when your employer or consulting client does. If the code you wrote belongs to the boss, after all, it isn’t yours. And if it isn’t yours, you don’t have the right to assign the copyright to an open source project. So let’s look, first, at the assumption that employment or freelance work is automatically work for hire.

For example, that little project of yours that you've been working on during your off-hours at work? It's probably yours but... as Daniel A. Tysver, a partner at Beck & Tysver wrote on BitLaw:

"Software developers should pay close attention to copyright ownership issues when hiring computer programmers. Programs written by salaried employees will, in almost all cases, be considered works made for hire. …

As a result, the software developer itself will be considered the author of the software written by those employees, and ownership will properly reside with the developer. However, the prudent developer will nonetheless have employees sign agreements whereby they agree to assign all copyrights in software they develop to the software developer. The reason for this prudence is that the determination of who is an employee under the law of agency requires an analysis of many factors and might cause unexpected results in rare cases. In addition, the work made for hire doctrine requires that the work be done 'within the scope of' the employee's employment. Generally, programs written by a software programmer employee will be within the scope of his or her employment, but this again is an ambiguous phrase that is best not to rely upon."

What if you're a freelance programmer and you're writing code under a "work for hire" contract? Does your client then own the copyright to the code you wrote – whether or not it’s part of an open source project as well? Well... actually maybe they do, maybe they don't.

Tysver continued:

Software developers must be especially careful when hiring contract programmers. In order for the work of contract programmers to be considered a work made for hire, three facts must exist:

The program must be specially ordered or commissioned;

The contract retaining the programmer must be in writing and must explicitly say that the programs created under the agreement are to be considered a work made for hire; and

The program created must fall into one of the nine enumerated categories of work.

The first element will generally be true when the programmer is hired to work on a specific project. The second element can be met through careful drafting of contract programmer's retainer agreement. The third element, however, can be more difficult. Computer software programs are not one of the nine enumerated categories. The best bet is to fit the software program under the definition of an "audiovisual work." While some software programs are clearly audiovisual works, it is unclear whether courts will allow this phrase to include all computer software programs. Thus, a software developer cannot be sure whether the contract programmer is creating a work made for hire.

It is best to draft an agreement which reflects this uncertainty. The agreement should state that the work is a work made for hire. However, the agreement should also state that if the software is not considered a work made for hire, the contract programmer agrees to assign the copyright in the software to the software developer.

Finally, when hiring a company to provide contract programming services, it is important to make sure that the copyright ownership passes all the way from the individual programmer to the software developer. Therefore, the software developer should review not only its agreement with the company providing the services, but also the agreements by which that company hires individual programmers.

Is he saying that that work-for-hire contract you signed that didn't spell who got the copyright for the code means you may still have the copyright? Well, yes, actually he is. If you take a close look at U.S. Copyright law (PDF), you'll find that there are nine classes of work that are described as “work made for hire” (WMFH). None of them are programming code.

So, as an author wrote on Law-Forums.org, under the nom de plume of morcan, “Computer programs do not generally fall into any of the statutory categories for commissioned WMFH and therefore, simply calling it that still won't conform to the statute."

He or she continued, "Therefore, you can certainly have a written WMFH agreement (for what it's worth) that expressly outlines the intent of the parties that you be the 'author and owner of the copyright' of the commissioned work, but you still need a (separate) transfer and assignment of all right, title and interest of the contractor's copyright of any and all portions of the works created under the project, which naturally arises from his or her being the author of the WMFH." In other words, without a “transfer of copyright ownership” clause in your contract, you the programmer, not the company that gave you the contract, may still have the copyright.

That

can lead to real trouble. "I have actually seen major corporate

acquisitions get scuttled because someone at the target software company

had 'contracted programmers' under WMFH agreements but failed to obtain

the necessary written transfer of the contractors' copyrights,” morcan

added.

That

can lead to real trouble. "I have actually seen major corporate

acquisitions get scuttled because someone at the target software company

had 'contracted programmers' under WMFH agreements but failed to obtain

the necessary written transfer of the contractors' copyrights,” morcan

added.

Rich Santalesa, senior counsel at InformationLawGroup, agreed with morcan. “What tends to happen is that cautious (read: solid) software/copyright attorneys use a belt and suspenders approach, adding into the development agreement that it’s 'to the full extent applicable' a 'Work for Hire' — in the event, practically, that the IRS or some other taxing entity says 'no that person is an employee and not an independent contractor,’” said Santalesa. They also include a transfer and assignment provision that is effective immediately upon execution.

“Whenever and wherever possible we [copyright attorneys representing the contracting party for the work] attempt to apply a Work for Hire situation,” explained Santalesa. “So the writer/programmer is, for copyright purposes, never the 'legal author.' It can get tricky, and as always the specific facts matter, with the proof ultimately in the contractual pudding that comes out of the oven.”

What I take all this to mean is you should make darn sure that both you and the company that contracted you have a legal contract spelling out exactly what happens to the copyright of any custom code. Simply saying something is a work for hire doesn't cut the mustard.

Now, Add in Open Source Contributions

These same concerns also apply to open source projects. Most projects have some kind of copyright assignment agreements (CAAs) or copyright licensing agreements (CLAs) you must sign before the code you write is committed to the project. In CAAs, you assign your copyright to a company or organization; in CLAs you give the group a broad license to work with your code.

While some open source figures, such as Bradley Kuhn of the Software Freedom Conservancy, don't want either kind of copyright agreement in open source software, almost all projects have them.

And they can often cause headaches.

Take, for example, the recent copyright fuss in the GnuTLS project, a free software implementation of the SSL (Secure Socket Layer) protocol. The project's founder, and one of its two main authors, Nikos Mavrogiannopoulos, announced in December 2012 that he was moving the project outside the infrastructure of the GNU project because of a major disagreement with the Free Software Foundation’s (FSF) decisions and practices. “I no longer consider GnuTLS a GNU project,” he wrote, “and future contributions are not required to be under the copyright of FSF.”

Richard M. Stallman, founder of GNU and the FSF, wasn't having any of that! In an e-mail entitled, GNUTLS is not going anywhere, Stallman, a.k.a. RMS, replied, "You cannot take GNUTLS out of the GNU Project. You cannot designate a non-GNU program as a replacement for a GNU package. We will continue the development of GNUTLS."

You see, while you don't have to assign your copyright to the FSF when you create a GNU project, the FSF won't protect the project's IP under the GPL unless you do make that assignment. And, back when the project started, Mavrogiannopoulos had transferred the copyrights. In addition, no matter where you are in the world, as RMS noted, if you do elect this path, the copyright goes to the U.S. FSF, not to one of its sister organizations.

After many heated words, this particular conflict calmed down. Mavrogiannopoulos now wishes he had made a different decision. “I pretty much regret transferring all rights to FSF, but it seems there is nothing I can do to change that.” He can fork the code, but he can't take the project's name with him since that's part of the copyright.

That may sound as though it’s getting far afield of The Least I Need to Know About Copyright as an Open Source Developer, but bear with me for a moment. Because it raises several troubling issues

As Michael Kerrisk, a LWN.net author put it, "The first of these problems has already been shown above: Who owns the project? The GnuTLS project was initiated in good faith by Nikos as a GNU project. Over the lifetime of the project, the vast majority of the code contributed to the project has been written by two individuals, both of whom (presumably) now want to leave the GNU project. If the project had been independently developed, then clearly Nikos and Simon would be considered to own the project code and name. However, in assigning copyright to the FSF, they have given up the rights of owners.”

However, there's more. As Kerrisk pointed out, “The ability of the FSF—as the sole copyright holder—to sue license violators is touted as one of the major advantages of copyright assignment. However, what if, for one reason or another, the FSF chooses not to exercise its rights?" What advantage does the programmer get then from assigning his or her copyright?

Finally, Kerrisk added, there's a problem that occurs with assignment both to companies and to non-profits. “The requirement to sign a copyright assignment agreement imposes a barrier on participation. Some individuals and companies simply won't bother with doing the paperwork. Others may have no problem contributing code under a free software license, but they (or their lawyers) balk at giving away all rights in the code.”

Can You Contribute to a Project? Legally?

The barrier to participation isn't just theoretical. Kerrisk cites the example of Greg Kroah-Hartman, the well-known Linux kernel developer. Kroah-Hartman, during a conversation about whether the Gentoo Linux distribution should seek copyright assignments, said, "On a personal note, if any copyright assignment was in place, I would never have been able to become a Gentoo developer, and if it were to be put into place, I do not think that I would be allowed to continue to be one. I'm sure lots of other current developers are in this same situation.”

Other non-profit open source groups take different approaches. The Apache Foundation, for instance, asks for "a perpetual, worldwide, non-exclusive, no-charge, royalty-free, irrevocable copyright license to reproduce, prepare derivative works of, publicly display, publicly perform, sublicense, and distribute Your Contributions and such derivative works."

If you have any questions about a particular group—and you should have questions—check to see exactly what rights the group requires in its contributor license agreement. Then, if you still have questions (you probably will) check with the organization or an IP attorney. This is not a check-mark that you ignore as blithely as all those websites where you click on “I have read and will adhere to the privacy policy.” In a literal sense you are committing yourself, or at least the code you wrote in all those bleary-eyed debugging sessions that required three cups of coffee.

The assignment of rights is not just a copyright problem for non-profit open source groups. Several commercial open source organizations ask you to give them your contributed code's copyright for their projects. Others, such as Oracle (PDF) asks for joint copyright to any of your contributions for its OpenJDK, GlassFish, and MySQL projects.

Some companies, such as Ubuntu Linux's parent company, Canonical, have backed off on asking for these claims. Canonical, for instance, now states that “You retain ownership of the Copyright in Your Contribution and have the same rights to use or license the Contribution which You would have had without entering into the Agreement." Red Hat, in its Fedora Project Contributor Agreement now asks only that you have the right to grant use of the copyrighted code and that it be licensed under either the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License or a variation of the MIT License. If you don't know what is being asked of you, get expert advice.

With all these differences in how to handle copyright disagreements you might wonder why someone hasn't tried to come with one common way of handling them. Well, they have: It’s called Project Harmony. However, Project Harmony hasn't picked up a lot of support and its copyright templates have not been widely accepted.

The bottom line isn't that you have to become a lawyer to code—although I could understand how you might feel that way!—but you do have to carefully examine what rights you have to your code. You need to understand what rights you're giving up or sharing with an open source license and a particular project. And if you're still puzzled, you need to seek expert legal help.

You don't want to find yourself in a copyright quagmire. Good luck.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (130841)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101439)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (99857)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57668)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57239)