Wednesday, October 30. 2013

Facebook may start tracking your cursor as you browse the site

Via The Verge

-----

For some time Facebook has studied your Likes, comments, and clicks to help create better ads and new products, but soon, the company might also track the location of your cursor on screen. Facebook analytics chief Ken Rudin told The Wall Street Journal about several new measures the company is testing meant to help improve its user-tracking, like seeing how long you hover your cursor over an ad (and if you click it), and evaluating if certain elements on screen are within view or are off the page. New data gathered using these methods could help Facebook create more engaging News Feed layouts and ads.

The Journal notes that this kind of tracking is hardly uncommon, but until now, Facebook hadn't gone this deep in its behavioral data measurement. Sites like Shutterstock, for example, track how long users hover their cursors over an image before deciding to buy it. Facebook is famous for its liberal use of A/B testing to try out new products on consumers, but it's using the same method to judge the efficacy of its new testing methods. "Facebook should know within months whether it makes sense to incorporate the new data collection into the business," reports the Journal.

Assuming Facebook's tests go well, it shouldn't be long before our every flinch is tracked on the site. So what might come next? Our eyeballs.

Monday, October 21. 2013

This Crazy Program Turns Wikipedia Into 3D Models of the Real World

Via Gizmodo

----

Google puts a lot of work into creating a virtual map of the world with Street View, sending cars and backpackers everywhere with huge cameras. But what if a computer program could do all that automatically? Well, there's one that can. All it needs is Wikipedia and Google Images.

Developed by Bryan Russell at Intel Labs and some colleagues at the University of Washington in Seattle, the program is almost deceptively simple. First, it trawls the internet (mainly Flickr) for a wide variety of pictures of a location. By looking at them from different angles, it's able to piece together a pretty good idea of what it looks like in 3D space from the outside. Like this:

Then, for the interior of that 3D shell, the program cruises through Wikipedia, making note of every single noun-phrase, since its dumb robot brain can't tell what is important and what is not. Finally, it searches Google Images for its big stack of phrases, pulls the relevant pictures (if it can find any), and plasters them roughly where they belong in the model's interior. When that's all said and done, it can then behave as a procedurally generated 3D tour that guides you through a recreation of whatever you're reading about on Wikipedia. Awesome!

It's a crazy idea, but it seems to work pretty well for popular landmarks, at least. The operating logic here is that if a thing is important, there will be pictures of it on the internet, and text describing the pictures. So long as that's true, it's possible to start piecing things together.

For the moment, the program has only compiled complete virtual representations of exceedingly popular and well-documented sites like the Sistine Chapel. With less common places, there's less data to pull. But with the advent of tech like Google Glass, and the wide proliferation of smartphones that can take a half-decent picture, the data-voids are slowly getting filled in—and they'll only fill in faster as time goes on.

So if you ever needed a great reason to keep all your vacation pictures public and publicly indexed, here it is. [Bryan C. Russell via New Scientist]

Wednesday, October 16. 2013

What Big Data Knows About Us

Via Mashable

-----

The world of Big Data is one of pervasive data collection and aggressive analytics. Some see the future and cheer it on; others rebel. Behind it all lurks a question most of us are asking — does it really matter? I had a chance to find out recently, as I got to see what Acxiom, a large-scale commercial data aggregator, had collected about me.

At least in theory large-scale data collection matters quite a bit. Large data sets can be used to create social network maps and can form the seeds for link analysis of connections between individuals. Some see this as a good thing; others as a bad one — but whatever your viewpoint, we live in a world which sees increasing power and utility in Big Data’s large-scale data sets.

Of course, much of the concern is about government collection. But it’s difficult to assess just how useful this sort of data collection by the government is because, of course, most governmental data collection projects are classified. The good news, however, is that we can begin to test the utility of the program in the private sector arena. A useful analog in the private sector just became publicly available and it’s both moderately amusing and instructive to use it as a lens for thinking about Big Data.

Acxiom is one of the largest commercial, private sector data aggregators around. It collects and sells large data sets about consumers — sometimes even to the government. And for years it did so quietly, behind the scene — as one writer put it “mapping the consumer genome.” Some saw this as rather ominous; others as just curious. But it was, for all of us, mysterious. Until now.

In September, the data giant made available to the public a portion of its data set. They created a new website — Abouthedata.com — where a consumer could go to see what data the company had collected about them. Of course, in order to access the data about yourself you had to first verify your own identity (I had to send in a photocopy of my driver’s license), but once you had done so, it would be possible to see, in broad terms, what the company thought it knew about you — and how close that knowledge was to reality.

I was curious, so I thought I would go explore myself and see what it was they knew and how accurate they were. The results were at times interesting, illuminating and mundane. Here are a few observations:

To begin with, the fundamental purpose of the data collection is to sell me things — that’s what potential sellers want to know about potential buyers and what, say, Amazon might want to know about me. So I first went and looked at a category called “Household Purchase Data” — in other words what I had recently bought.

It turns out that I buy … well … everything. I buy food, beverages, art, computing equipment, magazines, men’s clothing, stationary, health products, electronic products, sports and leisure products, and so forth. In other words, my purchasing habits were, to Acxiom, just an undifferentiated mass. Save for the notation that I had bought an antique in the past and that I have purchased “High Ticket Merchandise,” it seems that almost everything I bought was something that most any moderately well-to-do consumer would buy.

I do suppose that the wide variety of purchases I made is, itself, the point — by purchasing so widely I self-identify as a “good” consumer. But if that’s the point then the data set seems to miss the mark on “how good” I really am. Under the category of “total dollars spent,” for example, it said that I had spent just $1,898 in the past two years. Without disclosing too much about my spending habits in this public forum, I think it is fair to say that this is a significant underestimate of my purchasing activity.

The next data category of “Household Interests” was equally unilluminating. Acxiom correctly said I was interested in computers, arts, cooking, reading and the like. It noted that I was interested in children’s items (for my grandkids) and beauty items and gardening (both my wife’s interest, probably confused with mine). Here, as well, there was little differentiation, and I assume the breadth of my interests is what matters rather that the details. So, as a consumer, examining what was collected about me seemed to disclose only a fairly anodyne level of detail.

[Though I must object to the suggestion that I am an Apple user J. Anyone who knows me knows I prefer the Windows OS. I assume this was also the result of confusion within the household and a reflection of my wife’s Apple use. As an aside, I was invited throughout to correct any data that was in error. This I chose not to do, as I did not want to validate data for Acxiom – that’s their job not mine—and I had no real interest in enhancing their ability to sell me to other marketers. On the other hand I also did not take the opportunity they offered to completely opt-out of their data system, on the theory that a moderate amount of data in the world about me may actually lead to being offered some things I want to purchase.]

Things became a bit more intrusive (and interesting) when I started to look at my “Characteristic Data” — that is data about who I am. Some of the mistakes were a bit laughable — they pegged me as of German ethnicity (because of my last name, naturally) when, with all due respect to my many German friends, that isn’t something I’d ever say about myself. And they got my birthday wrong — lord knows why.

But some of their insights were at least moderately invasive of my privacy, and highly accurate. Acxiom “inferred” for example, that I’m married. They identified me accurately as a Republican (but notably not necessarily based on voter registration — instead it was the party I was “associated with by voter registration or as a supporter”). They knew there were no children in my household (all grown up) and that I run a small business and frequently work from home. And they knew which sorts of charities we supported (from surveys, online registrations and purchasing activity). Pretty accurate, I’d say.

Finally, it was completely unsurprising that the most accurate data about me was closely related to the most easily measurable and widely reported aspect of my life (at least in the digital world) — namely, my willingness to dive into the digital financial marketplace.

Acxiom knew that I had several credit cards and used them regularly. It had a broadly accurate understanding of my household total income range [I’m not saying!].Acxiom knew that I had several credit cards and used them regularly.

They also knew all about my house — which makes sense since real estate and liens are all matters of public record. They knew I was a home owner and what the assessed value was. The data showed, accurately, that I had a single family dwelling and that I’d lived there longer than 14 years. It disclosed how old my house was (though with the rather imprecise range of having been built between 1900 and 1940). And, of course, they knew what my mortgage was, and thus had a good estimate of the equity I had in my home.

So what did I learn from this exercise?

In some ways, very little. Nothing in the database surprised me, and the level of detail was only somewhat discomfiting. Indeed, I was more struck by how uninformative the database was than how detailed it was — what, after all, does anyone learn by knowing that I like to read? Perhaps Amazon will push me book ads, but they already know I like to read because I buy directly from them. If they had asserted that I like science fiction novels or romantic comedy movies, that level of detail might have demonstrated a deeper grasp of who I am — but that I read at all seems pretty trivial information about me.

I do, of course, understand that Acxiom has not completely lifted the curtains on its data holdings. All we see at About The Data is summary information. You don’t get to look at the underlying data elements. But even so, if that’s the best they can do ….

In fact, what struck me most forcefully was (to borrow a phrase from Hannah Arendt) the banality of it all. Some, like me, see great promise in big data analytics as a way of identifying terrorists or tracking disease. Others, with greater privacy concerns, look at big data and see Big Brother. But when I dove into one big data set (albeit only partially), held by one of the largest data aggregators in the world, all I really became was a bit bored.

Maybe that’s what they wanted as a way of reassuring me. If so, Acxiom succeeded, in spades.

Monday, October 07. 2013

How Google Converted Language Translation Into a Problem of Vector Space Mathematics

-----

To translate one language into another, find the linear transformation that maps one to the other. Simple, say a team of Google engineers

Computer science is changing the nature of the translation of words and sentences from one language to another. Anybody who has tried BabelFish or Google Translate will know that they provide useful translation services but ones that are far from perfect.

The basic idea is to compare a corpus of words in one language with the same corpus of words translated into another. Words and phrases that share similar statistical properties are considered equivalent.

The problem, of course, is that the initial translations rely on dictionaries that have to be compiled by human experts and this takes significant time and effort.

Now Tomas Mikolov and a couple of pals at Google in Mountain View have developed a technique that automatically generates dictionaries and phrase tables that convert one language into another.

The new technique does not rely on versions of the same document in different languages. Instead, it uses data mining techniques to model the structure of a single language and then compares this to the structure of another language.

“This method makes little assumption about the languages, so it can be used to extend and refine dictionaries and translation tables for any language pairs,” they say.

The new approach is relatively straightforward. It relies on the notion that every language must describe a similar set of ideas, so the words that do this must also be similar. For example, most languages will have words for common animals such as cat, dog, cow and so on. And these words are probably used in the same way in sentences such as “a cat is an animal that is smaller than a dog.”

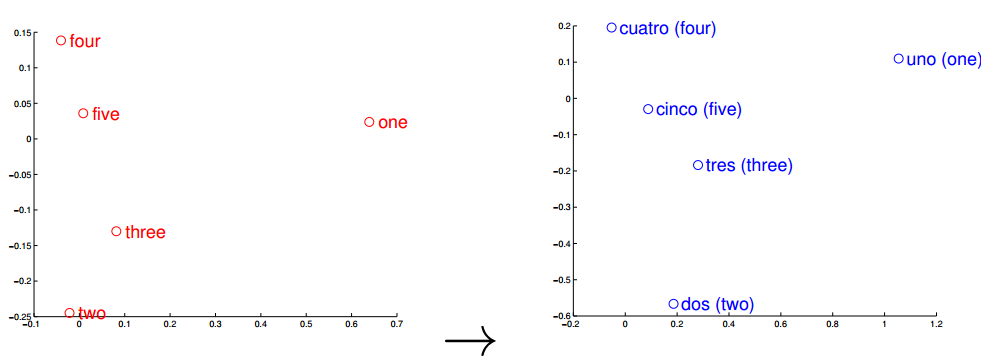

The same is true of numbers. The image above shows the vector representations of the numbers one to five in English and Spanish and demonstrates how similar they are.

This is an important clue. The new trick is to represent an entire language using the relationship between its words. The set of all the relationships, the so-called “language space”, can be thought of as a set of vectors that each point from one word to another. And in recent years, linguists have discovered that it is possible to handle these vectors mathematically. For example, the operation ‘king’ – ‘man’ + ‘woman’ results in a vector that is similar to ‘queen’.

It turns out that different languages share many similarities in this vector space. That means the process of converting one language into another is equivalent to finding the transformation that converts one vector space into the other.

This turns the problem of translation from one of linguistics into one of mathematics. So the problem for the Google team is to find a way of accurately mapping one vector space onto the other. For this they use a small bilingual dictionary compiled by human experts–comparing same corpus of words in two different languages gives them a ready-made linear transformation that does the trick.

Having identified this mapping, it is then a simple matter to apply it to the bigger language spaces. Mikolov and co say it works remarkably well. “Despite its simplicity, our method is surprisingly effective: we can achieve almost 90% precision@5 for translation of words between English and Spanish,” they say.

The method can be used to extend and refine existing dictionaries, and even to spot mistakes in them. Indeed, the Google team do exactly that with an English-Czech dictionary, finding numerous mistakes.

Finally, the team point out that since the technique makes few assumptions about the languages themselves, it can be used on argots that are entirely unrelated. So while Spanish and English have a common Indo-European history, Mikolov and co show that the new technique also works just as well for pairs of languages that are less closely related, such as English and Vietnamese.

That’s a useful step forward for the future of multilingual communication. But the team says this is just the beginning. “Clearly, there is still much to be explored,” they conclude.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1309.4168: Exploiting Similarities among Languages for Machine Translation

Thursday, October 03. 2013

Somebody Stole 7 Milliseconds From the Federal Reserve

Via Mother Jones

-----

Last Wednesday, the Fed announced that it would not be tapering its bond buying program. This news was released at precisely 2 p.m. in Washington "as measured by the national atomic clock." It takes seven milliseconds for this information to get to Chicago. However, several huge orders that were based on the Fed's decision were placed on Chicago exchanges two to three milliseconds after 2 p.m. How did this happen?

CNBC has the story here, and the answer is: We don't know. Reporters get the Fed release early, but they get it in a secure room and aren't permitted to communicate with the outside world until precisely 2 p.m. Still, maybe someone figured out a way to game the embargo. It would certainly be worth a ton of money. Investigations are ongoing, but Neil Irwin has this to say:

"In the meantime, there's another useful lesson out of the whole episode. It is the reality of how much trading activity, particularly of the ultra-high-frequency variety is really a dead weight loss for society.

…There is a role in [capital] markets for traders whose work is more speculative…But when taken to its logical extremes, such as computers exploiting five millisecond advantages in the transfer of market-moving information, it's much less clear that society gains anything…In the high-frequency trading business, billions of dollars are spent on high-speed lines, programming talent, and advanced computers by funds looking to capitalize on the smallest and most fleeting of mispricings. Those are computing resources and insanely intelligent people who could instead be put to work making the Internet run faster for everyone, or figuring out how to distribute electricity more efficiently, or really anything other than trying to figure out how to trade gold futures on the latest Fed announcement faster than the speed of light."

Yep. I'm not sure what to do about it, though. A tiny transaction tax still seems like a workable solution, although there are several real-world issues with it. Worth a look, though.

In a related vein, let's talk a bit more about this seven millisecond figure. That might very well be how long it takes a signal to travel from Washington, DC, to Chicago via a fiber-optic cable, but in fact the two cities are only 960 kilometers apart. At the speed of light, that's 3.2 milliseconds. A straight line path would be a bit less, perhaps 3 milliseconds. So maybe someone has managed to set up a neutrino communications network that transmits directly through the earth. It couldn't transfer very much information, but if all you needed was a few dozen bits (taper/no taper, interest rates up/down, etc.) it might work a treat. Did anyone happen to notice an extra neutrino flux in the upper Midwest corridor at 2 p.m. last Wednesday? Perhaps Wall Street has now co-opted not just the math geek community, and not just the physics geek community, but the experimental physics geek community. Wouldn't that be great?

Wednesday, October 02. 2013

UW engineers invent programming language to build synthetic DNA

-----

Yan Liang, L2XY2.com

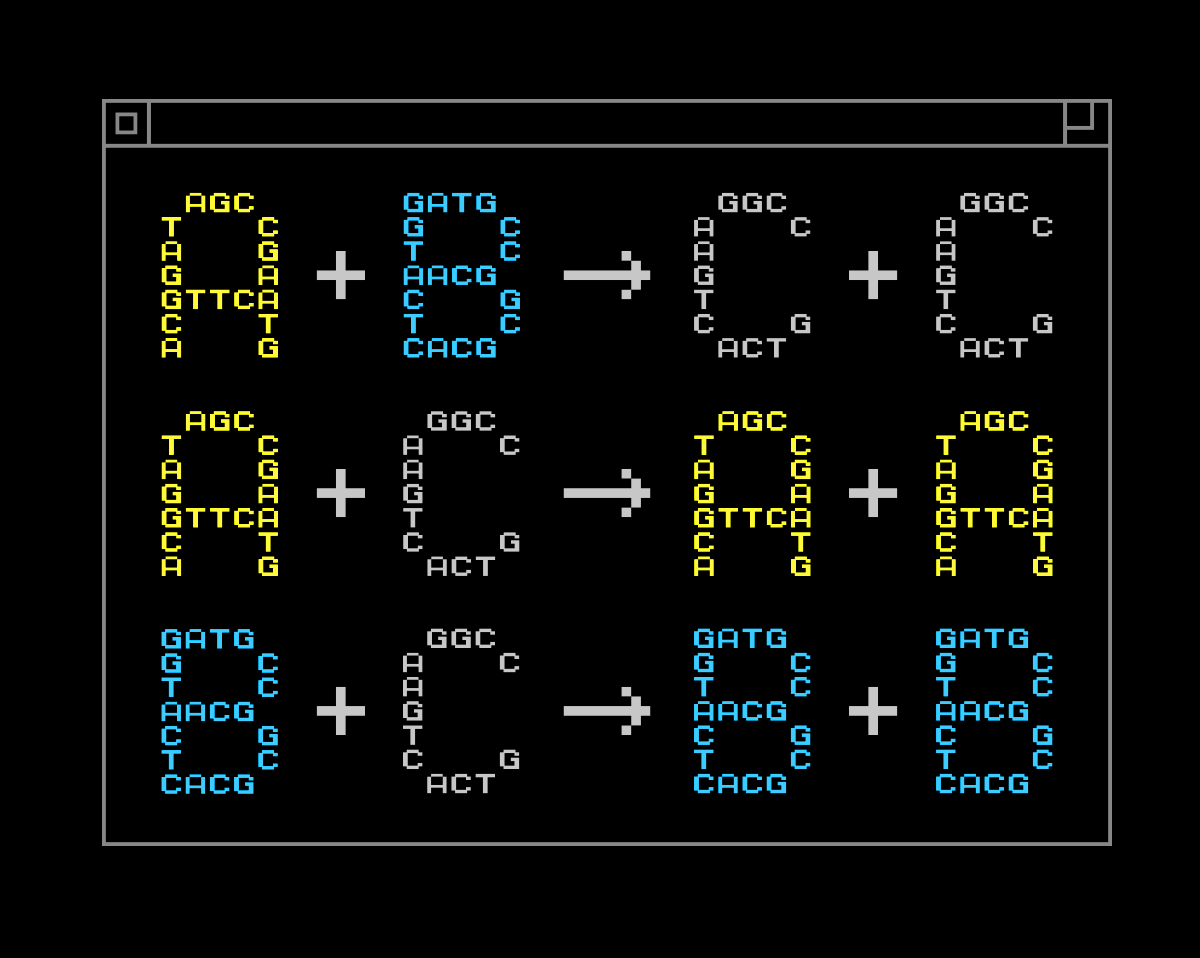

An example of a chemical program. Here, A, B and C are different chemical species.

Similar to using Python or Java to write code for a computer, chemists soon could be able to use a structured set of instructions to “program” how DNA molecules interact in a test tube or cell.

A team led by the University of Washington has developed a programming language for chemistry that it hopes will streamline efforts to design a network that can guide the behavior of chemical-reaction mixtures in the same way that embedded electronic controllers guide cars, robots and other devices. In medicine, such networks could serve as “smart” drug deliverers or disease detectors at the cellular level.

The findings were published online this week (Sept. 29) in Nature Nanotechnology.

Chemists and educators teach and use chemical reaction networks, a century-old language of equations that describes how mixtures of chemicals behave. The UW engineers take this language a step further and use it to write programs that direct the movement of tailor-made molecules.

“We start from an abstract, mathematical description of a chemical system, and then use DNA to build the molecules that realize the desired dynamics,” said corresponding author Georg Seelig, a UW assistant professor of electrical engineering and of computer science and engineering. “The vision is that eventually, you can use this technology to build general-purpose tools.”

Currently, when a biologist or chemist makes a certain type of molecular network, the engineering process is complex, cumbersome and hard to repurpose for building other systems. The UW engineers wanted to create a framework that gives scientists more flexibility. Seelig likens this new approach to programming languages that tell a computer what to do.

“I think this is appealing because it allows you to solve more than one problem,” Seelig said. “If you want a computer to do something else, you just reprogram it. This project is very similar in that we can tell chemistry what to do.”

Humans and other organisms already have complex networks of nano-sized molecules that help to regulate cells and keep the body in check. Scientists now are finding ways to design synthetic systems that behave like biological ones with the hope that synthetic molecules could support the body’s natural functions. To that end, a system is needed to create synthetic DNA molecules that vary according to their specific functions.

The new approach isn’t ready to be applied in the medical field, but future uses could include using this framework to make molecules that self-assemble within cells and serve as “smart” sensors. These could be embedded in a cell, then programmed to detect abnormalities and respond as needed, perhaps by delivering drugs directly to those cells.

Seelig and colleague Eric Klavins, a UW associate professor of electrical engineering, recently received $2 million from the National Science Foundation as part of a national initiative to boost research in molecular programming. The new language will be used to support that larger initiative, Seelig said.

Co-authors of the paper are Yuan-Jyue Chen, a UW doctoral student in electrical engineering; David Soloveichik of the University of California, San Francisco; Niranjan Srinivas at the California Institute of Technology; and Neil Dalchau, Andrew Phillips and Luca Cardelli of Microsoft Research.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the National Centers for Systems Biology.

Tuesday, October 01. 2013

France sanctions Google for European privacy law violations

Via pcworld

-----

Google faces financial sanctions in France after failing to comply with an order to alter how it stores and shares user data to conform to the nation's privacy laws.

The enforcement follows an analysis led by European data protection authorities of a new privacy policy that Google enacted in 2012, France's privacy watchdog, the Commission Nationale de L'Informatique et des Libertes, said Friday on its website.

Google was ordered in June by the CNIL to comply with French data protection laws within three months. But Google had not changed its policies to comply with French laws by a deadline on Friday, because the company said that France's data protection laws did not apply to users of certain Google services in France, the CNIL said.

The company "has not implemented the requested changes," the CNIL said.

As a result, "the chair of the CNIL will now designate a rapporteur for the purpose of initiating a formal procedure for imposing sanctions, according to the provisions laid down in the French data protection law," the watchdog said. Google could be fined a maximum of €150,000 ($202,562), or €300,000 for a second offense, and could in some circumstances be ordered to refrain from processing personal data in certain ways for three months.

What bothers France

The CNIL took issue with several areas of Google's data policies, in particular how the company stores and uses people's data. How Google informs users about data that it processes and obtains consent from users before storing tracking cookies were cited as areas of concern by the CNIL.

In a statement, Google said that its privacy policy respects European law. "We have engaged fully with the CNIL throughout this process, and we'll continue to do so going forward," a spokeswoman said.

Google is also embroiled with European authorities in an antitrust case for allegedly breaking competition rules. The company recently submitted proposals to avoid fines in that case.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (130841)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101439)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (99855)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57668)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57238)