Monday, November 25. 2013

Microsoft debuts 3D printing app for Windows 8.1

Via pcworld

-----

On Friday, Microsoft released its 3D Builder app, which allows Windows 8.1 users to print 3D objects, but not much else.

The simple, simplistic, free app from Microsoft provides a basic way to print common 3D objects, as well as to import other files from SkyDrive or elsewhere. But the degree of customization that the app allows is small, so 3D Builder basically serves as an introduction to the world of 3D printing.

In fact, that’s Microsoft’s intention, with demonstrations of the MakerBot Replicator 2 slated for Microsoft’s retails stores this weekend. Microsoft customers can buy a new Windows 8.1 PC, as well as the $2199 MakerBot Replicator 2, both online as well as in the brick-and-mortar stores themselves.

One of the selling points of Windows 8.1 was its ability to print 3D objects, a complement to traditional paper printing. Although Microsoft is pitching 3D Builder as a consumer app, the bulk of spending on 3D printing will come from businesses, which will account for $325 million out of the $415 million that will be spent this year on 3D printing, according to an October report from Gartner. However, 3D printers have made their way into Staples, and MakerBot latched onto an endorsement of the technology from President Obama during his State of the Union address, recently encouraging U.S. citizens to crowd-fund an effort to 3D printers in every high school in America. (MakerBot also announced a Windows 8.1 software driver on Thursday.)

Microsoft

MicrosoftMicrosoft’s 3D Builder app could certainly be a part of that effort. Frankly, there’s little to the app itself besides a library of pre-selected objects, most of which seem to be built around small, unpowered model trains of the “Thomas the Tank Engine” variety. After selecting one, the user has the option of moving it around a 3D space, increasing or decreasing the size to a particular width or height—and not much else.

Users can also import models made elsewhere. Again, however, 3D Builder isn’t really designed to modify the designs. It’s also not clear which 3D formats are supported.

On the other hand, some might be turned off by the perceived complexity of 3D printing. If you have two grand to spend on a 3D printer but aren’t really sure how to use it, 3D Builder might be a good place to start.

Friday, November 22. 2013

Apple II DOS source code - The Computer History Museum Historical Source Code Series

-----

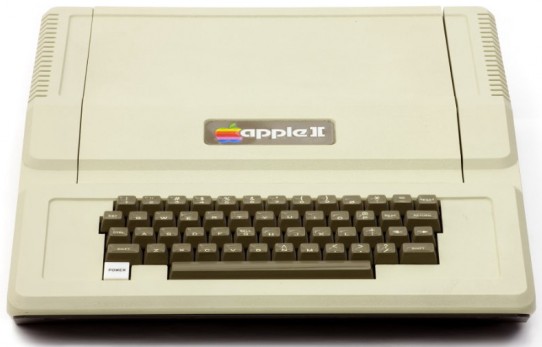

In June 1977 Apple Computer shipped their first mass-market computer:

the Apple II.

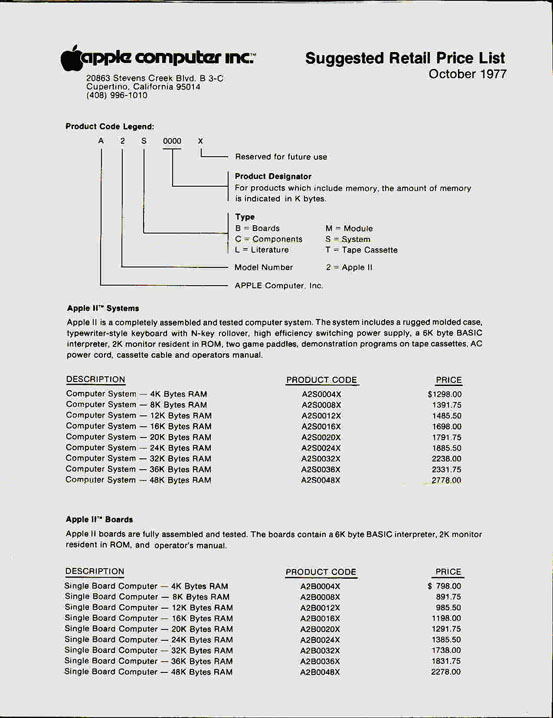

Unlike the Apple I, the Apple II was fully assembled and ready to use with any display monitor. The version with 4K of memory cost $1298. It had color, graphics, sound, expansion slots, game paddles, and a built-in BASIC programming language.

What it didn’t have was a disk drive. Programs and data had to be saved and loaded from cassette tape recorders, which were slow and unreliable. The problem was that disks – even floppy disks – needed both expensive hardware controllers and complex software.

Steve Wozniak solved the first problem. He designed an incredibly clever floppy disk controller using only 8 integrated circuits, by doing in programmed logic what other controllers did with hardware. With some rudimentary software written by Woz and Randy Wigginton, it was demonstrated at the Consumer Electronics Show in January 1978.

But where were they going to get the higher-level software to organize and access programs and data on the disk? Apple only had about 15 employees, and none of them had both the skills and the time to work on it.

The magician who pulled that rabbit out of the hat was Paul Laughton, a contract programmer for Shepardson Microsystems, which was located in the same Cupertino office park as Apple.

On April 10, 1978 Bob Shepardson and Steve Jobs signed a $13,000 one-page contract for a file manager, a BASIC interface, and utilities. It specified that “Delivery will be May 15?, which was incredibly aggressive. But, amazingly, “Apple II DOS version 3.1? was released in June 1978.

With thanks to Paul Laughton, in collaboration with Dr. Bruce Damer, founder and curator of the DigiBarn Computer Museum, and with the permission of Apple Inc., we are pleased to make available the 1978 source code of Apple II DOS for non-commercial use. This material is Copyright © 1978 Apple Inc., and may not be reproduced without permission from Apple.

There are seven files in this release that may be downloaded by clicking the hyperlinked filename on the left:

| Apple_DOS_2June1978.pdf | Scanned lineprinter listing from June 2, 1978 |

| Apple_DOS_6Oct1978.pdf | Scanned lineprinter listing from October 6, 1978 |

| Apple_DOS_6Oct1978_retyped.docx | Retyped source code of the October 6th version (This has not yet been assembled, and there may be some typographical errors.) |

| Apple_DOS_RW_30May1978.txt | The source code of the low-level read/write routines by Steve Wozniak and Randy Wigginton. |

| Apple_DOS_tech_docs.pdf | Various technical specifications and designs relating to the Apple II disk drive |

| Apple_DOS_contracts.pdf | Various contracts and addenda between Apple and Shepardson Microsystems |

| meeting_minutes_5Oct1978.pdf | Minutes of a meeting between Apple and Shepardson Microsystem about bugs and enhancements. (Unfortunately we don’t have the list that is referred to.) |

Friday, November 15. 2013

Wolfram: "Something Very Big Is Coming: Our Most Important Technology Project Yet"

Via Wolfram blog

-----

Computational knowledge. Symbolic programming. Algorithm automation. Dynamic interactivity. Natural language. Computable documents. The cloud. Connected devices. Symbolic ontology. Algorithm discovery. These are all things we’ve been energetically working on—mostly for years—in the context of Wolfram|Alpha, Mathematica, CDF and so on.

But recently something amazing has happened. We’ve figured out how to take all these threads, and all the technology we’ve built, to create something at a whole different level. The power of what is emerging continues to surprise me. But already I think it’s clear that it’s going to be profoundly important in the technological world, and beyond.

At some level it’s a vast unified web of technology that builds on what we’ve created over the past quarter century. At some level it’s an intellectual structure that actualizes a new computational view of the world. And at some level it’s a practical system and framework that’s going to be a fount of incredibly useful new services and products.

I have to admit I didn’t entirely see it coming. For years I have gradually understood more and more about what the paradigms we’ve created make possible. But what snuck up on me is a breathtaking new level of unification—that lets one begin to see that all the things we’ve achieved in the past 25+ years are just steps on a path to something much bigger and more important.

I’m not going to be able to explain everything in this blog post (let’s hope it doesn’t ultimately take something as long as A New Kind of Science

to do so!). But I’m excited to begin to share some of what’s been

happening. And over the months to come I look forward to describing some

of the spectacular things we’re creating—and making them widely

available.

It’s hard to foresee the ultimate consequences of what we’re doing. But the beginning is to provide a way to inject sophisticated computation and knowledge into everything—and to make it universally accessible to humans, programs and machines, in a way that lets all of them interact at a vastly richer and higher level than ever before.

A crucial building block of all this is what we’re calling the Wolfram Language.

In a sense, the Wolfram Language has been incubating inside Mathematica for more than 25 years. It’s the language of Mathematica, and CDF—and the language used to implement Wolfram|Alpha. But now—considerably extended, and unified with the knowledgebase of Wolfram|Alpha—it’s about to emerge on its own, ready to be at the center of a remarkable constellation of new developments.

We call it the Wolfram Language because it is a language. But it’s a new and different kind of language. It’s a general-purpose knowledge-based language. That covers all forms of computing, in a new way.

There are plenty of existing general-purpose computer languages. But their vision is very different—and in a sense much more modest—than the Wolfram Language. They concentrate on managing the structure of programs, keeping the language itself small in scope, and relying on a web of external libraries for additional functionality. In the Wolfram Language my concept from the very beginning has been to create a single tightly integrated system in which as much as possible is included right in the language itself.

And so in the Wolfram Language, built right into the language, are capabilities for laying out graphs or doing image processing or creating user interfaces or whatever. Inside there’s a giant web of algorithms—by far the largest ever assembled, and many invented by us. And there are then thousands of carefully designed functions set up to use these algorithms to perform operations as automatically as possible.

Over the years, I’ve put immense effort into the design of the language. Making sure that all the different pieces fit together as smoothly as possible. So that it becomes easy to integrate data analysis here with document generation there, with mathematical optimization somewhere else. I’m very proud of the results—and I know the language has been spectacularly productive over the course of a great many years for a great many people.

But now there’s even more. Because we’re also integrating right into the language all the knowledge and data and algorithms that are built into Wolfram|Alpha. So in a sense inside the Wolfram Language we have a whole computable model of the world. And it becomes trivial to write a program that makes use of the latest stock price, computes the next high tide, generates a street map, shows an image of a type of airplane, or a zillion other things.

We’re also getting the free-form natural language of Wolfram|Alpha. So when we want to specify a date, or a place, or a song, we can do it just using natural language. And we can even start to build up programs with nothing more than natural language.

There are so many pieces. It’s quite an array of different things.

But what’s truly remarkable is how they assemble into a unified whole.

Partly that’s the result of an immense amount of work—and discipline—in the design process over the past 25+ years. But there’s something else too. There’s a fundamental idea that’s at the foundation of the Wolfram Language: the idea of symbolic programming, and the idea of representing everything as a symbolic expression. It’s been an embarrassingly gradual process over the course of decades for me to understand just how powerful this idea is. That there’s a completely general and uniform way to represent things, and that at every level that representation is immediately and fluidly accessible to computation.

It can be an array of data. Or a piece of graphics. Or an algebraic formula. Or a network. Or a time series. Or a geographic location. Or a user interface. Or a document. Or a piece of code. All of these are just symbolic expressions which can be combined or manipulated in a very uniform way.

But in the Wolfram Language, there’s not just a framework for setting up these different kinds of things. There’s immense built-in curated content and knowledge in each case, right in the language. Whether it’s different types of visualizations. Or different geometries. Or actual historical socioeconomic time series. Or different forms of user interface.

I don’t think any description like this can do the concept of symbolic programming justice. One just has to start experiencing it. Seeing how incredibly powerful it is to be able to treat code like data, interspersing little programs inside a piece of graphics, or a document, or an array of data. Or being able to put an image, or a user interface element, directly into the code of a program. Or having any fragment of any program immediately be runnable and meaningful.

In most languages there’s a sharp distinction between programs, and data, and the output of programs. Not so in the Wolfram Language. It’s all completely fluid. Data becomes algorithmic. Algorithms become data. There’s no distinction needed between code and data. And everything becomes both intrinsically scriptable, and intrinsically interactive. And there’s both a new level of interoperability, and a new level of modularity.

So what does all this mean? The idea of universal computation implies that in principle any computer language can do the same as any other. But not in practice. And indeed any serious experience of using the Wolfram Language is dramatically different than any other language. Because there’s just so much already there, and the language is immediately able to express so much about the world. Which means that it’s immeasurably easier to actually achieve some piece of functionality.

I’ve put a big emphasis over the years on automation. So that the Wolfram Language does things automatically whenever you want it to. Whether it’s selecting an optimal algorithm for something. Or picking the most aesthetic layout. Or parallelizing a computation efficiently. Or figuring out the semantic meaning of a piece of data. Or, for that matter, predicting what you might want to do next. Or understanding input you’ve given in natural language.

Fairly recently I realized there’s another whole level to this. Which has to do with the actual deployment of programs, and connectivity between programs and devices and so on. You see, like everything else, you can describe the infrastructure for deploying programs symbolically—so that, for example, the very structure and operation of the cloud becomes data that your programs can manipulate.

And this is not just a theoretical idea. Thanks to endless layers of software engineering that we’ve done over the years—and lots of automation—it’s absolutely practical, and spectacular. The Wolfram Language can immediately describe its own deployment. Whether it’s creating an instant API, or putting up an interactive web page, or creating a mobile app, or collecting data from a network of embedded programs.

And what’s more, it can do it transparently across desktop, cloud, mobile, enterprise and embedded systems.

It’s been quite an amazing thing seeing this all start to work. And being able to create tiny programs that deploy computation across different systems in ways one had never imagined before.

This is an incredibly fertile time for us. In a sense we’ve got a new paradigm for computation, and every day we’re inventing new ways to use it. It’s satisfying, but more than a little disorienting. Because there’s just so much that is possible. That’s the result of the unique convergence of the different threads of technology that we’ve been developing for so long.

Between the Wolfram Language—with all its built-in computation and knowledge, and ways to represent things—and our Universal Deployment System, we have a new kind of universal platform of incredible power. And part of the challenge now is to find the best ways to harness it.

Over the months to come, we’ll be releasing a series of products that support particular ways of using the Wolfram Engine and the Universal Platform that our language and deployment system make possible.

There’ll be the Wolfram Programming Cloud, that allows one to create Wolfram Language programs, then instantly deploy them in the cloud through an instant API, or a form-based app, or whatever. Or deploy them in a private cloud, or, for example, through a Function Call Interface, deploy them standalone in desktop programs and embedded systems. And have a way to go from an idea to a fully deployed realization in an absurdly short time.

There’ll be the Wolfram Data Science Platform, that allows one to connect to all sorts of data sources, then use the kind of automation seen in Wolfram|Alpha Pro, then pick out and modify Wolfram Language programs to do data science—and then use CDF to set up reports to generate automatically, on a schedule, through an API, or whatever.

There’ll be the Wolfram Publishing Platform that lets you create documents, then insert interactive elements using the Wolfram Language and its free-form linguistics—and then deploy the documents, on the web using technologies like CloudCDF, that instantly support interactivity in any web browser, or on mobile using the Wolfram Cloud App.

And we’ll be able to advance Mathematica a lot too. Like there’ll be Mathematica Online, in which a whole Mathematica session runs on the cloud through a web browser. And on the desktop, there’ll be seamless integration with the Wolfram Cloud, letting one have things like persistent symbolic storage, and instant large-scale parallelism.

And there’s still much more; the list is dauntingly long.

Here’s another example. Just as we curate all sorts of data and algorithms, so also we’re curating devices and device connections. So that built into the Wolfram Language, there’ll be mechanisms for communicating with a very wide range of devices. And with our Wolfram Embedded Computation Platform, we’ll have the Wolfram Language running on all sorts of embedded systems, communicating with devices, as well as with the cloud and so on.

At the center of everything is the Wolfram Language, and we intend to make this as widely accessible to everyone as possible.

The Wolfram Language is a wonderful first language to learn (and we’ve done some very successful experiments on this). And we’re planning to create a Programming Playground that lets anyone start to use the language—and through the Programming Cloud even step up to make some APIs and so on for free.

We’ve also been building the Wolfram Course Authoring Platform, that does major automation of the process of going from a script to all the elements of an online course—then lets one deploy the course in the cloud, so that students can have immediate access to a Wolfram Language sandbox, to be able to explore the material in the course, do exercises, and so on. And of course, since it’s all based on our unified system, it’s for example immediate that data from the running of the course can go into the Wolfram Data Science Platform for analysis.

I’m very excited about all the things that are becoming possible. As the Wolfram Language gets deployed in all these different places, we’re increasingly going to be able to have a uniform symbolic representation for everything. Computation. Knowledge. Content. Interfaces. Infrastructure. And every component of our systems will be able to communicate with full semantic fidelity, exchanging Wolfram Language symbolic expressions.

Just as the lines between data, content and code blur, so too will the lines between programming and mere input. Everything will become instantly programmable—by a very wide range of people, either by using the Wolfram Language directly, or by using free-form natural language.

There was a time when every computer was in a sense naked—with just its basic CPU. But then came things like operating systems. And then various built-in languages and application programs. What we have now is a dramatic additional step in this progression. Because with the Wolfram Language, we can in effect build into our computers a vast swath of existing knowledge about computation and about the world.

If we’re forming a kind of global brain with all our interconnected computers and devices, then the Wolfram Language is the natural language for it. Symbolically representing both the world and what can be created computationally. And, conveniently enough, being efficient and understandable for both computers and humans.

The foundations of all of this come from decades spent on Mathematica, and Wolfram|Alpha, and A New Kind of Science. But what’s happening now is something new and unexpected. The emergence, in effect, of a new level of computation, supported by the Wolfram Language and the things around it.

So far I can see only the early stages of what this will lead to. But already I can tell that what’s happening is our most important technology project yet. It’s a lot of hard work, but it’s incredibly exciting to see it all unfold. And I can’t wait to go from “Coming Soon” to actual systems that people everywhere can start to use…

Sunday, November 03. 2013

Watch 15 Awesome MS-DOS Viruses in Action

Via Wired

-----

-

Elvira, virus by French programmer Spanska, replicated the Star Wars opening crawl in an ode to his girlfriend. Image: danooct1

Elvira, virus by French programmer Spanska, replicated the Star Wars opening crawl in an ode to his girlfriend. Image: danooct1 -

Virus.DOS.Phantom1 is menacing--but also clearly a labor of love. Image: danooct1

Virus.DOS.Phantom1 is menacing--but also clearly a labor of love. Image: danooct1 -

Virus.DOS.Walker displays a crude bit of 8-bit porno (not shown) and then has an old man stroll across your screen. Image: danooct1

Virus.DOS.Walker displays a crude bit of 8-bit porno (not shown) and then has an old man stroll across your screen. Image: danooct1 -

Virus.DOS.Kuku infects all EXE and COM files, and, one time out of eight, displays this lovely colorful confetti on your screen. Image: danooct1

Virus.DOS.Kuku infects all EXE and COM files, and, one time out of eight, displays this lovely colorful confetti on your screen. Image: danooct1 -

Virus.DOS.Plane unleashes a parachuter on your command line, creating infected companion files for COMs and EXEs. Image: danooct1

Virus.DOS.Plane unleashes a parachuter on your command line, creating infected companion files for COMs and EXEs. Image: danooct1 -

Virus.Boot.Pingpong doesn't destroy anything, but it does turn your screen into a game of ping pong (but only if you try to run files on the half hour [seriously]). Image: danooct1

Virus.Boot.Pingpong doesn't destroy anything, but it does turn your screen into a game of ping pong (but only if you try to run files on the half hour [seriously]). Image: danooct1 -

"Mars Land," another one of Spanksa's viruses, shows a lovely lava flow with a nice message: Coding a virus can be creative. Image: danooct1

"Mars Land," another one of Spanksa's viruses, shows a lovely lava flow with a nice message: Coding a virus can be creative. Image: danooct1 -

Markt DOS Virus looks scary--and it is: it formats your entire C drive. Image: danooct1

Markt DOS Virus looks scary--and it is: it formats your entire C drive. Image: danooct1 -

Ithaqua DOS Virus is just plain nice. Every April 29 it takes over your screen to show a gentle snowfall. Image: danooct1

Ithaqua DOS Virus is just plain nice. Every April 29 it takes over your screen to show a gentle snowfall. Image: danooct1 -

Virus.DOS.Billiards turns your boring text into a colorful game of pool. Nice! Image: danooct1

Virus.DOS.Billiards turns your boring text into a colorful game of pool. Nice! Image: danooct1 -

Virus.DOS.HHnHH, a bouncing particle ball, wouldn't make a bad screensaver. Image: danooct1

Virus.DOS.HHnHH, a bouncing particle ball, wouldn't make a bad screensaver. Image: danooct1 -

Apple DOS Trojan proves that even in the underground world of DOS viruses, fanboys were fanboys. Image: danooct1

Apple DOS Trojan proves that even in the underground world of DOS viruses, fanboys were fanboys. Image: danooct1 -

PlayGame DOS Virus makes the unfortunate user play a game upon booting up, but only in December. Image: danooct1

PlayGame DOS Virus makes the unfortunate user play a game upon booting up, but only in December. Image: danooct1 -

Virus.DOS.Redcode plays out a little race between Big Butt Gasso and Himmler Fewster. Weird. Image: danooct1

Virus.DOS.Redcode plays out a little race between Big Butt Gasso and Himmler Fewster. Weird. Image: danooct1 -

CMOS DOS Virus is an evil virus indeed. Along with this seizure-inducing payload (and a shrieking beeping noise), it corrupts the CMOS memory, wiping all sorts of settings. The most diabolical bit? If you try to press Control Alt Delete, it reformats your whole hard drive. Image: danooct1

CMOS DOS Virus is an evil virus indeed. Along with this seizure-inducing payload (and a shrieking beeping noise), it corrupts the CMOS memory, wiping all sorts of settings. The most diabolical bit? If you try to press Control Alt Delete, it reformats your whole hard drive. Image: danooct1

Back in 2004, a computer worm called Sasser swept across the web, infecting an estimated quarter million PCs. One of them belonged to Daniel White, then 16 years old. In the course of figuring out how to purge the worm from his system, the teenager came across the website of anti-virus company F-Secure, which hosted a vast field guide of malware dating back to the 1980s, complete with explanations, technical write-ups, and even screenshots for scores of antiquated viruses. He found it intoxicating. “I just read all I could,” he says, “and when I’d read all of that I found more sources to read.” He’d caught the computer virus bug.

Nine years and a handful of data loss scares later, White has amassed perhaps the most comprehensive archive of malware-in-action found anywhere on the web. His YouTube channel, which he started in 2008, includes more than 450 videos, each dedicated to documenting the effect of some old, outdated virus. The contents span decades, stretching from the dawn of personal computing to the heyday of Windows in the late ’90s. It’s a fascinating cross-section of the virus world, from benign programs that trigger goofy, harmless pop-ups to malicious, hell-raising bits of code. Happening across one of White’s clips for a virus you’ve done battle with back in the day can be a surprisingly nostalgic experience.

But while the recent Windows worms may be the most familiar, another subset of White’s archive is even more interesting. The viruses he’s collected from the MS-DOS era are malware from a simpler time–a glimpse into a largely forgotten and surprisingly creative subculture.

“In the DOS era it was very much a hobbyist sort of thing,” White explains. Skilled coders wanted to show off their skills. They formed groups, and those groups pioneered different ways to infect and proliferate. A community coalesced around bulletin boards and newsgroups. Techniques were exchanged; rivalries bubbled up. For many writers, though, a successful virus didn’t necessarily mean messing up someone’s computer–or even letting users know that they’d been infected in the first place. Quietly, virus writers amassed invisible, harmless networks as testaments to their chops. “Not all authors were complete dicks,” White says. “There were far more viruses that only infected files and continued spreading than there were viruses that damaged data or displayed ‘gotcha’ messages.”

As we see here, though, some of those “gotcha” messages–a virus’ payload, as it’s called–were spectacularly unique. Amidst the dull monochromatic world of the command line, these viruses exploded to life. One, created by the French virus writer Spanska, flooded an infected machine’s display with a dramatic flow of digital lava. Another showed a menacing skull, clearly rendered with patience and care. Others were more playful: a billiards-themed virus turned command line text into a colorful game of pool, with letters bouncing around the display and knocking others along the way. Some were downright sweet. The Ithaqua DOS virus showed a gentle, pixelated snowfall accumulating on the infected machine’s screen–and only on one day a year.

For at least some of these mischievous coders, the virus truly did serve as a creative medium. When asked about his view on destructive code in a 1997 interview, Spanska, the French lava master, replied: “I really do not like that…There are two principal reasons why I will never put a destructive code inside one my viruses. First, I respect other peoples’ work…The second reason is that a destructive payload is too easy to code. Formatting a HD? Twenty lines of assembler, coded in one minute. Deleting a file? Five instructions. Written in one second. Easy things are not interesting for the coder. I prefer to spend weeks to code a beautiful VGA effect. I prefer create than destruct [sic]. It’s so important for me that I put this phrase in my MarsLand virus: ‘Coding a virus can be creative.’”

Of course, no matter how widely they might’ve spread in the weeks and months following their deployment, these old viruses were inevitably squelched. Systems were patched and upgrades rendered their exploits obsolete. Even the F-Secure database that sparked his obsession is largely inaccessible today, White points out, discarded in favor of a “more ‘consumer friendly’ website.” So White resolutely keeps on preserving the things–infecting virtual machines and filming the results. Now a graduate student specializing in satellite imaging systems, he still finds time to upload a new video every month or so, often working with files that tipsters send him to fill in holes in his collection. Thankfully for him and his hardware, the hobby isn’t quite as risky as you might think. “For the most part, the stuff I handle won’t do much of anything, if anything at all, on modern PCs and operating systems,” he says. But you never know. “I live by the philosophy ‘if you’re not willing to lose all the data on every PC on the network, don’t start toying with malware.’”

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131065)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101688)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100077)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57917)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57484)

Categories

Show tagged entries

Syndicate This Blog

Calendar

|

|

November '13 |

|

||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |