Security cameras that watch you, and predict what you'll do next, sound like science fiction. But a team from Carnegie Mellon University says their computerized surveillance software will be capable of "eventually predicting" what you're going to do.

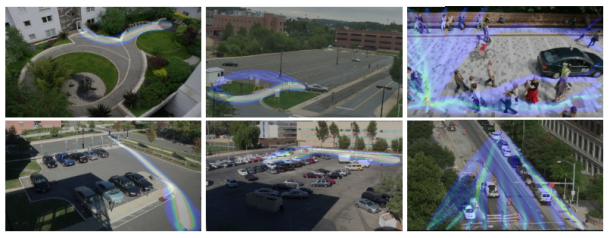

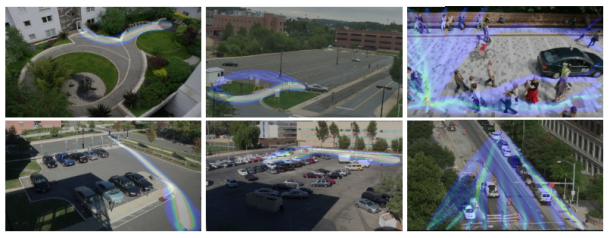

Computerized surveillance can predict what

people will do next -- it's called "activity forecasting" -- and

eventually sound the alarm if the action is not permitted. Click for

larger image.

(Credit:

Carnegie Mellon University)

Computer software programmed to detect and report illicit behavior could

eventually replace the fallible humans who monitor surveillance

cameras.

The U.S. government has funded the development of so-called automatic

video surveillance technology by a pair of Carnegie Mellon University

researchers who disclosed details about their work this week --

including that it has an ultimate goal of predicting what people will do

in the future.

"The main applications are in video surveillance, both civil and military," Alessandro Oltramari, a postdoctoral researcher at Carnegie Mellon who has a Ph.D. from Italy's University of Trento, told CNET yesterday.

Oltramari and fellow researcher Christian Lebiere

say automatic video surveillance can monitor camera feeds for

suspicious activities like someone at an airport or bus station

abandoning a bag for more than a few minutes. "In this specific case,

the goal for our system would have been to detect the anomalous

behavior," Oltramari says.

Think of it as a much, much smarter version of a red light camera: the

unblinking eye of computer software that monitors dozens or even

thousands of security camera feeds could catch illicit activities that

human operators -- who are expensive and can be distracted or sleepy --

would miss. It could also, depending on how it's implemented, raise

similar privacy and civil liberty concerns.

Alessandro Oltramari, left, and Christian

Lebiere say their software will "automatize video-surveillance, both in

military and civil applications."

(Credit:

Carnegie Mellon University)

A paper (PDF)

the researchers presented this week at the Semantic Technology for

Intelligence, Defense, and Security conference outside of Washington,

D.C. -- today's sessions are reserved

only for attendees with top secret clearances -- says their system aims

"to approximate human visual intelligence in making effective and

consistent detections."

Their Army-funded research, Oltramari and Lebiere claim, can go further

than merely recognizing whether any illicit activities are currently

taking place. It will, they say, be capable of "eventually predicting"

what's going to happen next.

This approach relies heavily on advances by machine vision researchers,

who have made remarkable strides in last few decades in recognizing

stationary and moving objects and their properties. It's the same vein

of work that led to Google's self-driving cars, face recognition software used on Facebook and Picasa, and consumer electronics like Microsoft's Kinect.

When it works well, machine vision can detect objects and people -- call

them nouns -- that are on the other side of the camera's lens.

But to figure out what these nouns are doing, or are allowed to do, you

need the computer science equivalent of verbs. And that's where

Oltramari and Lebiere have built on the work of other Carnegie Mellon

researchers to create what they call a "cognitive engine" that can

understand the rules by which nouns and verbs are allowed to interact.

Their cognitive engine incorporates research, called activity

forecasting, conducted by a team led by postdoctoral fellow Kris Kitani,

which tries to understand what humans will do by calculating which

physical trajectories are most likely. They say their software "models

the effect of the physical environment on the choice of human actions."

Both projects are components of Carnegie Mellon's Mind's Eye

architecture, a DARPA-created project that aims to develop smart cameras

for machine-based visual intelligence.

Predicts Oltramari: "This work should support human operators and automatize

video-surveillance, both in military and civil applications."