Entries tagged as internet

Friday, September 05. 2014

Via The Register

-----

Google is attempting to shunt users away from old browsers by

intentionally serving up a stale version of the ad giant's search

homepage to those holdouts.

The tactic appears to be falling in line with Mountain View's policy on its other Google properties, such as Gmail, which the company declines to fully support on aged browsers.

However, it was claimed on Friday in a Google discussion thread

that the multinational had unceremoniously dumped a past its

sell-by-date version of the Larry Page-run firm's search homepage on

those users who have declined to upgrade their Opera and Safari

browsers.

A user with the moniker DJSigma wrote on the forum:

A few minutes ago, Google's homepage reverted to the old version for

me. I'm using Opera 12.17. If I search for something, the results are

shown with the current Google look, but the homepage itself is the old

look with the black bar across the top. It seems to affect only the

Google homepage and image search. If I click on "News", for instance,

it's fine.

I've tried clearing cookies and deleting the browser cache/persistent

storage. I've tried disabling all extensions. I've tried masking the

browser as IE and Firefox. It doesn't matter whether I'm signed in or

signed out. Nothing works. Please fix this!

In a later post, DJSigma added that there seemed to be a glitch on Google search.

If I go to the Google homepage, I get served the old version of the

site. If I search for something, the results show up in the current

look. However, if I then try and type something into the search box

again, Google search doesn't work at all. I have to go back to the

homepage every time to do a new search.

The Opera user then said that the problem appeared to be

"intermittent". Others flagged up similar issues on the Google forum

and said they hoped it was just a bug.

While someone going by the name MadFranko008 added:

Phew ... thought it was just me and I'd been hacked or something ...

Same problem here everything "Google" has reverted back to the old style

of several years ago.

Tested on 3 different computers and different OS's & browsers ...

All have the same result, everything google has gone back to the old

style of several years ago and there's no way to change it ... Even the

copyright has reverted back to 2013!!!

Some Safari 5.1.x and Opera 12.x netizens were able to

fudge the system by customising their browser's user agent. But others

continued to complain about Google's "clunky", old search homepage.

A

Google employee, meanwhile, said that the tactic was deliberate in a

move to flush out stick-in-the-mud types who insisted on using older

versions of browsers.

"Thanks for the reports. I want to assure

you this isn't a bug, it's working as intended," said a Google worker

going by the name nealem. She added:

We’re continually making improvements to Search, so we can only

provide limited support for some outdated browsers. We encourage

everyone to make the free upgrade to modern browsers - they’re more

secure and provide a better web experience overall.

In a separate thread, as spotted by a Reg

reader who brought this sorry affair to our attention, user

MadFranko008 was able to show that even modern browsers - including the

current version of Chrome - were apparently spitting out glitches on

Apple Mac computers.

Google then appeared to have resolved the search "bug" spotted in Chrome.

Wednesday, July 16. 2014

Via Wired

-----

Illustration: dzima1/Getty

When Google chief financial officer Patrick Pichette said the tech giant might bring 10 gigabits per second internet connections

to American homes, it seemed like science fiction. That’s about 1,000

times faster than today’s home connections. But for NASA, it’s downright

slow.

While the rest of us send data across the public internet, the space agency uses a shadow network called ESnet, short for Energy Science Network, a set of private pipes that has demonstrated cross-country data transfers of 91 gigabits per second–the fastest of its type ever reported.

NASA isn’t going bring these speeds to homes, but it is using this

super-fast networking technology to explore the next wave of computing

applications. ESnet, which is run by the U.S. Department of Energy, is

an important tool for researchers who deal in massive amounts of data

generated by projects such as the Large Hadron Collider and the Human

Genome Project. Rather sending hard disks back and forth through the

mail, they can trade data via the ultra-fast network. “Our vision for

the world is that scientific discovery shouldn’t be constrained by

geography,” says ESnet director Gregory Bell.

In making its network as fast as it can possibly be, ESnet and

researchers are organizations like NASA are field testing networking

technologies that may eventually find their way into the commercial

internet. In short, ESnet a window into what our computing world will

eventually look like.

The Other Net

The first nationwide computer research network was the Defense

Department’s ARPAnet, which evolved into the modern internet. But it

wasn’t the last network of its kind. In 1976, the Department of Energy

sponsored the creation of the Magnetic Fusion Energy Network to connect

what is today the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center

with other research laboratories. Then the agency created a second

network in 1980 called the High Energy Physics Network to connect

particle physics researchers at national labs. As networking became more

important, agency chiefs realized it didn’t make sense to maintain

multiple networks and merged the two into one: ESnet.

The nature of the network changes with the times. In the early days

it ran on land lines and satellite links. Today it is uses fiber optic

lines, spanning the DOE’s 17 national laboratories and many other sites,

such as university research labs. Since 2010, ESnet and Internet2—a

non-profit international network built in 1995 for researchers after the

internet was commercialized—have been leasing “dark fiber,” the excess

network capacity built-up by commercial internet providers during the

late 1990s internet bubble.

An Internet Fast Lane

In November, using this network, NASA’s High End Computer Networking

team achieved its 91 gigabit transfer between Denver and NASA Goddard

Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. It was the fastest

end-to-end data transfer ever conducted under “real world” conditions.

ESnet has long been capable of 100 gigabit transfers, at least in

theory. Network equipment companies have been offering 100 gigabit

switches since 2010. But in practice, long-distance transfers were much

slower. That’s because data doesn’t travel through the internet in a

straight line. It’s less like a super highway and more like an

interstate highway system. If you wanted to drive from San Francisco to

New York, you’d pass through multiple cities along the way as you

transferred between different stretches of highway. Likewise, to send a

file from San Francisco to New York on the internet—or over ESnet—the

data will flow through hardware housed in cities across the country.

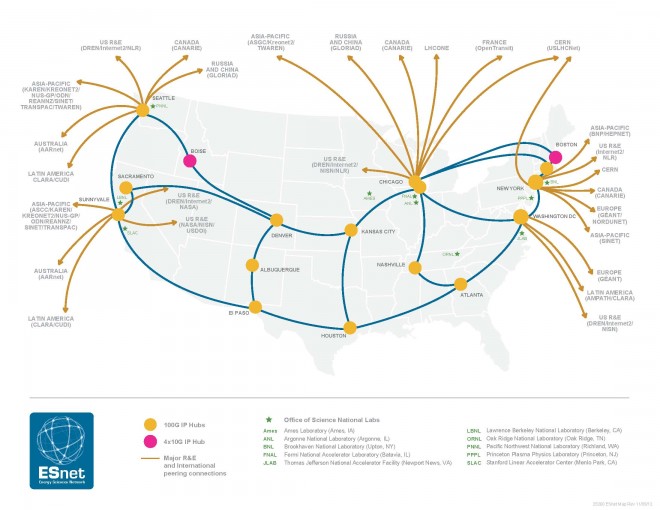

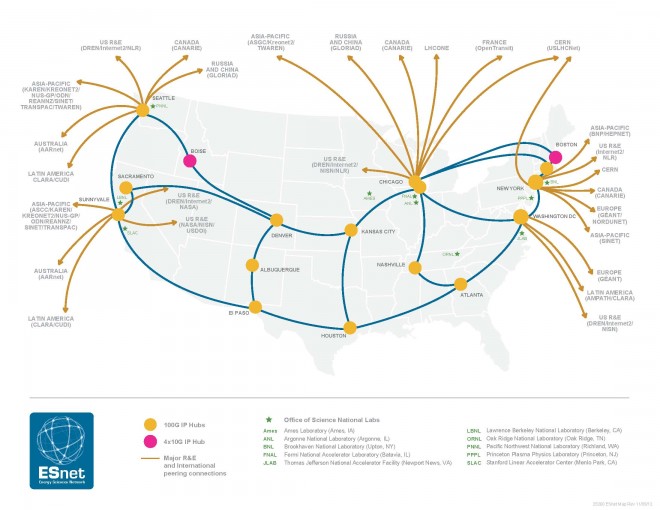

A map of ESnet’s connected sites. Image: Courtesy of ESnet

NASA did a 98 gigabit transfer between Goddard and the University of Utah over ESnet in 2012. And Alcatel-Lucent and BT obliterated that record

earlier this year with a 1.4 terabit connection between London and

Ipswich. But in both cases, the two locations had a direct connection,

something you rarely see in real world connections.

On the internet and ESnet, every stop along the way creates the

potential for a bottleneck, and every piece of gear must be ready to

handle full 100 gigabit speeds. In November, the team finally made it

work. “This demonstration was about using commercial, off-the-shelf

technology and being able to sustain the transfer of a large data

network,” says Tony Celeste, a sales director at Brocade, the company

that manufactured the equipment used in the record-breaking test.

Experiments for the Future

Meanwhile, the network is advancing the state of the art in other

ways. Researchers have used it to explore virtual network circuits

called “OSCARS,”

which can be used to create complex networks without complex hardware

changes. And they’re working on what are known as network “DMZs,” which can achieve unusually fast speeds by handling security without traditional network firewalls.

These solutions are designed specifically for networks in which a

small number of very large transfers take place–as opposed to the

commercial internet where lots of small transfers take place. But

there’s still plenty for commercial internet companies to learn from

ESnet. Telecommunications company XO Communications already has a 100 gigabit backbone, and we can expect more companies to follow suit.

Although we won’t see 10-gigabit connections—let alone 100 gigabit

connections—at home any time soon, higher capacity internet backbones

will mean less congestion as more and more people stream high-definition

video and download ever-larger files. And ESnet isn’t stopping there.

Bell says the organization is already working on a 400 gigabit network,

and the long-term goal is a terabyte per second network, which about

100,000 times faster than today’s home connections. Now that sounds like

science fiction.

Update 13:40 EST 06/17/14: This story has been updated to make it clear that ESnet is run by the Department of Energy.

Update 4:40 PM EST 06/17/14: This story has been updated to avoid

confusion between ESnet’s production network and its more experimental

test bed network.

Friday, June 20. 2014

Via TechCrunch

-----

Not very often do you read something online that gives you the chills. Today, I read two such things.

The first came from former Gizmodo, Buzzfeed and now Awl writer John Herrman, who wrote about the brutality of the mobile social (or for sake of discussion ‘fourth’) Internet:

“Metafilter came from two or three internets ago, when a

website’s core audience—people showing up there every day or every week,

directly—was its main source of visitors. Google might bless a site

with new visitors or take them away.

Either way, it was still possible for a site’s fundamentals to be

strong, independent of extremely large outside referrers. What’s so

disconcerting now is that the new sources of readership, the apps and

sites people check every day and which lead people to new posts and

stories, make up a majority of readership, and they’re utterly

unpredictable (they’re also bigger, always bigger, every new internet

is.)”

This broke my heart. In 2008, two Internets ago, Metafilter was my favorite site. It was where I went to find out what the next Star Wars Kid would be, or to find precious baby animal videos to show my cool boyfriend or even more intellectual fare. And now it’s as endangered as the sneezing pandas I first discovered there.

National Internet treasures like Metafilter (or TechCrunch

for that matter) should never die. There should be some Internet

Preservation Society filled with individuals like Herrman or Marc

Andreessen or Mark Zuckerberg or Andy Baio whose sole purpose is to keep them alive.

But there isn’t. Herrman makes a very good point; Useful places to

find information, that aren’t some strange Pavlovian manipulation of the

human desire to click or identify, just aren’t good business these

days.

And Herrman should know, he’s worked in every new media outlet under

the web, including the one that AP staffers are now so desperate to join

that they make mistakes like this.

The fourth Internet is scary like Darwinism, brutal enough to remind

me of high school. It’s a game of identity where you either make people

feel like members of some exclusive club, like The Information

does with a pricy subscription model or all niche tech sites do with

their relatively high CPM, or you straight up play up to reader

narcissism like Buzzfeed does, slicing and dicing user identity until

you end up with “21 Problems Only People With Baby Faces Will Understand.”

Which brings me to the thing I read today which truly scared the shit out of me. Buzzfeed founder Jonah Peretti, though his LinkedIn is completely bereft of it in favor of MIT, was apparently an undergrad at UC Santa Cruz in the late 90s.

Right after graduation in 1996, he wrote a paper

about identity and capitalism in post-modern times, which tl:dr

postulated that neo-capitalism needs to get someone to identify with its

ideals before it could sell its wares.

(Aside: If you think you are immune to capitalistic entreaties, because you read Adbusters and are a Culture Jammer,

you’re not. Think of it this way: What is actually wrong with being

chubby? But how hard do modern ads try to tell you that this — which is

arguably the Western norm — is somehow not okay.)

The thesis Peretti put forth in his paper is basically the blueprint for Buzzfeed, which increasingly has made itself All About You. Whether you’re an Armenian immigrant, or an Iggy Azaelia fan or

a person born in the 2000s, 1990s or 80s, you will identify with

Buzzfeed, because its business model (and the entire fourth Internet’s )

depends on it.

As Dylan Matthews writes:

“The way this identification

will happen is through images and video, through ‘visual culture.’

Presumably, in this late capitalist world, someone who creates a website

that can use pictures and GIFs and videos to form hundreds if not

thousands of new identities for people to latch onto will become very

successful!”

More than anything else in the pantheon of modern writing or as the

kids call it, content creation, Buzzfeed aims to be hyper-relatable,

through visuals! It hopes it can define your exact identity, because

only then will you share its URL on Facebook and Twitter and Tumblr as

some sort of badge of your own uniqueness, immortality.

If the first Internet was “Getting information online,” the second

was “Getting the information organized” and the third was “Getting

everyone connected” the fourth is definitely “Get mine.” Which is a

trap.

Which Cog In The Digital Capitalist Machine Are You?

Friday, June 13. 2014

Via TechCrunch

-----

There is no point in kidding ourselves, now, about Who Has the Power.

– Hunter S. Thompson, jacket copy, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

The Internet wasn’t supposed to be so…Machiavellian.

In 1963, Stewart Brand

and his wife set out on a landmark road trip, the goal of which was to

educate and enliven the people they encountered with tools for modern

living. The word “tools” was taken liberally. Brand wrote that “a realm

of intimate, personal power is developing.” Any tool that created or

channeled such power was useful. Tools meant books, maps, professional journals, courses, classes, and more.

In 1968, Brand founded the Whole Earth Catalog (WEC), an underground

magazine of sorts that would scale in a way no road-weary Dodge ever

could. The first issue was 64 pages and cost $5. It opened with the

phrase: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.”

A year after WEC’s start, on October 29, 1969, the first packet of data was sent from UCLA to SRI International. It was called ARPAnet

at the time, but with it the Internet was born. Brand and others would

come to see the Internet as the essential, defining “tool” of their

generation. Until its final issue in 1994, the WEC’s 32 editions provide

as good a chronicle of the emergence of cyberculture (as it was then

called) as you can find.

Cyberculture. It’s a curious and complicated term in today’s society,

isn’t it? Cyberculture is at once completely outdated and awfully

relevant.

As Fred Turner has argued,

Brand is a key figure in the weaving together of two major cultural

fabrics that have since split — counterculture and cyberculture. Brand

is also immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test as a member of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters. And Brand famously assisted researcher Doug Engelbart with the “Mother of all Demos,” the outline of a vision for technology prosthetics that improve human life; it would define computing for decades to come.

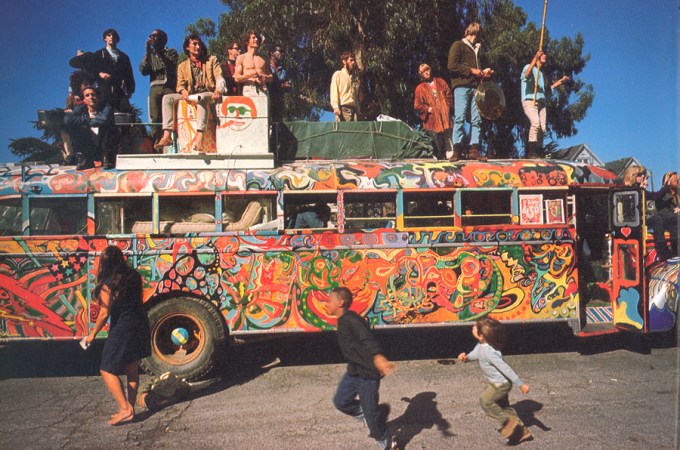

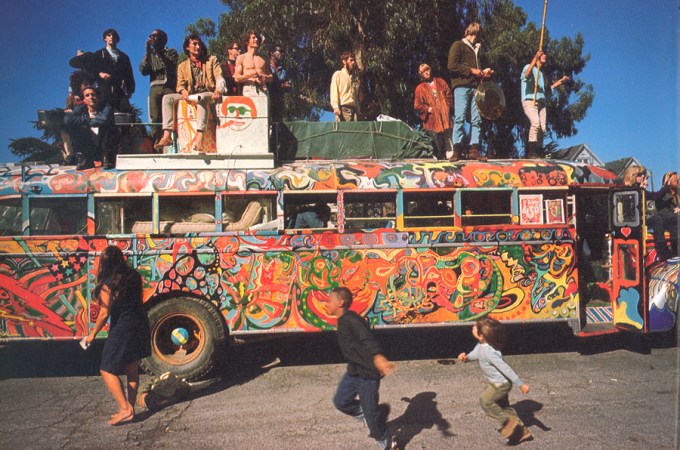

The Merry Pranksters, still from the movie Magic Trip

Brand attended Phillips Exeter Academy — an elite East Coast high

school, and an institution of traditional power if there ever was one.

He was a parachutist in the U.S. Army. He graduated with a degree in

biology from Stanford, studied design at San Francisco Art Institute and

photography at San Francisco State. He also participated in legal

studies of LSD and its effects with Timothy Leary.

That’s hardly the typical resume of a technologist or an entrepreneur

or an investor. But it should be. The business of making culture has

been for too long now controlled by people who live outside it.

It is my opinion that the Internet of today can and must be

countercultural again, that cyberculture should — needs to be —

countercultural.

That word, countercultural, carries with it

the connotation of liberal idealism and societal marginalia. Yet, the

new countercultures we’re seeing online today are profoundly mainstream,

and drawn along wholly different political lines. The Internet is its

own party. The Internet has its own set of beliefs. Springs have sprung

the world over and this isn’t simply a nerd thing anymore. We all care

passionately about Internet life and Internet liberty and the continual

pursuit of happiness both online and off.

Yet if the Internet is a measure of our culture, our zeitgeist, then

what does it tell us about the spirit of this age? Our zeitgeist

certainly isn’t what’s trending; it’s not another quiz of which TV

character you are; it’s not another listicle. I changed the global power

structure and all I got was this lousy t-shirt. And Facebook. And

Twitter.

What is this generation’s Rolling Stone? What is our Whole Earth

Catalog? It’s an important question because if the Internet is defining

our culture, and our use of it defines our society, then we have a

responsibility to ensure and propel its transformative impact, to

understand the ways cyberculture can and should be the counterculture

driving change rather than just distracting us from it.

There are beacons of hope. I eagerly await Jon Evans’ fantastic column in these pages each weekend for reasons like this.

The Daily Dot, a

publication I co-founded, documents today’s cyberculture through the

lens of online communities — virtual locales in which we arguably

“reside” more deliberately than any geography. You should also be

reading Edge, N+1, and Dangerous Minds. Even Vanity Fair has turned its eye to this theme, successfully I think, with articles like this. Rolling Stone is doing a pretty good job of being Rolling Stone these days, too.

I’m terminally optimistic, and I believe that counter-cyber-culture

is inherently optimistic, as well. Even despite the U.S. government’s

overreaching on privacy and “protecting” us from data about our own

bodies, despite Silicon Valley’s mad rush to cash in on apps rather than

substantial technology, despite most online media’s drastic descent to

the lowest common denominator and even lower standards of journalism, I

remain…optimistic.

We have found a courage in our growing numbers online. People old and

young can be be bold and defining on the Internet, underwritten by the

emotional support of peers everywhere. We’re voting for what we want the

world to be, and how we want it to be. Why do you think Kickstarter

works so well? We fund things that without our help are unlikely to

exist, but ought to nonetheless. Our “likes” and “shares” are ultimately

becoming votes for the kind of future we want to live in, and I’m

optimistic that we will ultimately wield that responsibility with

meaning and thoughtfully.

Tumblr. 4chan. Etsy. YouTube. We have emigrated to these outlying

territories seeking religious freedoms, cultural freedoms, and personal

freedoms alike. We colonized, and are still colonizing, new environs

each day and every week. We claim and reclaim the Internet like so many

tribal boundaries.

We’re winning more often than not, thank goodness. Aaron Swartz heroically beat SOPA and PIPA against all odds. Yahoo won against PRISM. The Internet won against cancer…with pizza. My godmother knows what Tor is.

The virtual reality community rebelled when princely Oculus sold to

Facebook, for the reason that VR is a new superpower and a new

countercultural medium that we’re afraid might have fallen into the

wrong hands (I don’t believe that’s actually the case, but that’s

grounds for another post altogether).

So, yes. A countercultural moment all our own stares us in the face.

Like Brand, I hope we can manage to be politically aware and socially

responsible in a way that technology begs us to be, without giving

ground to the idea that the Internet is anything but ours.

Civil disobedience is a different game when the means of production

and dissemination have been fully democratized. We seek differentiated

high ground from which to defend our values. We build new back channels

to communicate unencumbered. Instead of making catalogues, we make new

categories. We wield technology, perhaps unaware on whose shoulders we

stand, but at the same time free from the anxiety of influence.

We aspire to be more pure in that sense. We want and we give and we need and we will have…pure Internet.

Editor’s note: Josh Jones-Dilworth is a co-founder of the Daily Dot; founder and CEO of Jones-Dilworth, Inc., an early-stage technology marketing consultancy; and co-founder of Totem, a startup changing PR for the better. Follow his blog here.

Featured image by Kundra/Shutterstock; Hunter S. Thompson image by Wikimedia Commons user MDCarchives (own work) under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license

Wednesday, May 14. 2014

Via The Verge

-----

The internet will have nearly 3 billion users, about 40 percent of the world's population, by the end of 2014, according to a new report from the United Nations International Telecommunications Union. Two-thirds of those users will be in developing countries.

Those numbers refer to people who have used the internet in the last three months, not just those who have access to it.

Internet penetration is

reaching saturation in developed countries, while it's growing rapidly

in developing countries. Three out of four people in Europe will be

using the internet by the end of the year, compared to two out of three

in the Americas and one in three in Asia and the Pacific. In Africa,

nearly one in five people will be online by the end of the year.

Mobile phone subscriptions will

reach almost 7 billion. That growth rate is slowing, suggesting that

the number will plateau soon. Mobile internet subscriptions are still

growing rapidly, however, and are expected to reach 2.3 billion by the

end of 2014.

These numbers make it easy to

imagine a future in which every human on Earth is using the internet.

The number of people online will still be dwarfed by the number of

things, however. Cisco estimates the internet already has 10 billion

connected devices and is expected to hit 50 billion by 2020.

Saturday, November 16. 2013

Via The Guardian, Via Samantha Besson

-----

NSA spying, as

revealed by the whistleblower Edward Snowden, may cause countries to

create separate networks and break up the experts, according to experts.

Photograph: Alex Milan Tracy/NurPhoto/NurPhoto/Corbis

The vast scale of online surveillance revealed by Edward Snowden is leading to the breakup of the internet

as countries scramble to protect private or commercially sensitive

emails and phone records from UK and US security services, according to

experts and academics.

They say moves by countries, such as Brazil and Germany,

to encourage regional online traffic to be routed locally rather than

through the US are likely to be the first steps in a fundamental shift

in the way the internet works. The change could potentially hinder

economic growth.

"States may have few other options than to follow

in Brazil's path," said Ian Brown, from the Oxford Internet Institute.

"This would be expensive, and likely to reduce the rapid rate of

innovation that has driven the development of the internet to date … But

if states cannot trust that their citizens' personal data – as well as

sensitive commercial and government information – will not otherwise be

swept up in giant surveillance operations, this may be a price they are

willing to pay."

Since the Guardian's revelations about the scale

of state surveillance, Brazil's government has published ambitious plans

to promote Brazilian networking technology, encourage regional internet

traffic to be routed locally, and is moving to set up a secure national

email service.

In India, it has been reported that government employees are being advised not to use Gmail

and last month, Indian diplomatic staff in London were told to use

typewriters rather than computers when writing up sensitive documents.

In Germany, privacy commissioners have called for a review of whether Europe's internet traffic can be kept within the EU – and by implication out of the reach of British and US spies.

Surveillance dominated last week's Internet Governance Forum 2013,

held in Bali. The forum is a UN body that brings together more than

1,000 representatives of governments and leading experts from 111

countries to discuss the "sustainability, robustness, security,

stability and development of the internet".

Debates on child

protection, education and infrastructure were overshadowed by widespread

concerns from delegates who said the public's trust in the internet was

being undermined by reports of US and British government surveillance.

Lynn

St Amour, the Internet Society's chief executive, condemned government

surveillance as "interfering with the privacy of citizens".

Johan

Hallenborg, Sweden's foreign ministry representative, proposed that

countries introduce a new constitutional framework to protect digital

privacy, human rights and to reinforce the rule of law.

Meanwhile,

the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers – which is

partly responsible for the infrastructure of the internet – last week

voiced "strong concern over the undermining of the trust and confidence

of internet users globally due to recent revelations of pervasive

monitoring and surveillance".

Daniel Castro, a senior analyst at

the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation in Washington,

said the Snowden revelations were pushing the internet towards a tipping

point with huge ramifications for the way online communications worked.

"We

are certainly getting pushed towards this cliff and it is a cliff we do

not want to go over because if we go over it, I don't see how we stop.

It is like a run on the bank – the system we have now works unless

everyone decides it doesn't work then the whole thing collapses."

Castro

said that as the scale of the UK and US surveillance operations became

apparent, countries around the globe were considering laws that would

attempt to keep data in-country, threatening the cloud system – where

data stored by US internet firms is accessible from anywhere in the

world.

He said this would have huge implications for the way large companies operated.

"What

this would mean is that any multinational company suddenly has lots of

extra costs. The benefits of cloud computing that have given us

flexibility, scaleability and reduced costs – especially for large

amounts of data – would suddenly disappear."

Large internet-based firms, such as Facebook and Yahoo, have already raised concerns about the impact of the NSA

revelations on their ability to operate around the world. "The

government response was, 'Oh don't worry, we're not spying on any

Americans'," said Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. "Oh, wonderful:

that's really helpful to companies trying to serve people around the

world, and that's really going to inspire confidence in American

internet companies."

Castro wrote a report for Itif in August

predicting as much as $35bn could be lost from the US cloud computing

market by 2016 if foreign clients pull out their businesses. And he said

the full economic impact of the potential breakup of the internet was

only just beginning to be recognised by the global business community.

"This

is changing how companies are thinking about data. It used to be that

the US government was the leader in helping make the world more secure

but the trust in that leadership has certainly taken a hit … This is

hugely problematic for the general trust in the internet and e-commerce

and digital transactions."

Brown said that although a localised

internet would be unlikely to prevent people in one country accessing

information in another area, it may not be as quick and would probably

trigger an automatic message telling the user that they were entering a

section of the internet that was subject to surveillance by US or UK

intelligence.

"They might see warnings when information is about

to be sent to servers vulnerable to the exercise of US legal powers – as

some of the Made in Germany email services that have sprung up over the summer are."

He

said despite the impact on communications and economic development, a

localised internet might be the only way to protect privacy even if, as

some argue, a set of new international privacy laws could be agreed.

"How

could such rules be verified and enforced? Unlike nuclear tests,

internet surveillance cannot be detected halfway around the world."

Thursday, March 28. 2013

Via Internet Census 2012

-----

Abstract While playing around with the Nmap Scripting Engine

(NSE) we discovered an amazing number of open embedded devices on the

Internet. Many of them are based on Linux and allow login to standard

BusyBox with empty or default credentials. We used these devices to

build a distributed port scanner to scan all IPv4 addresses. These scans

include service probes for the most common ports, ICMP ping, reverse

DNS and SYN scans. We analyzed some of the data to get an estimation of

the IP address usage.

All data gathered during our research is released into the public domain for further study.

The full study

Continue reading "Internet Census 2012 - Port scanning /0 using insecure embedded devices"

Tuesday, March 05. 2013

Via Slash Gear

-----

Google will be conducting a 45-day public trial

with the FCC to create a centralized database containing information on

free spectrum. The Google Spectrum Database will analyze TV white

spaces, which are unused spectrum between TV stations, that can open

many doors for possible wireless spectrum expansion in the future. By

unlocking these white spaces, wireless providers will be able to provide

more coverage in places that need it.

The public trial brings Google

one step closer to becoming a certified database administrator for

white spaces. Currently the only database administrators are Spectrum

Bridge, Inc. and Telcordia Technologies, Inc. Many other companies are

applying to be certified, including a big dog like Microsoft. With companies like Google and Microsoft becoming certified, discovery of white spaces should increase monumentally.

Google’s trial allows all industry stakeholders, including

broadcasters, cable, wireless microphone users, and licensed spectrum

holders, to provide feedback to the Google Spectrum Database. It also

allows anyone to track how much TV white space is available in their

given area. This entire process is known as dynamic spectrum sharing.

Google’s trial, as well as the collective help of all the other

spectrum data administrators, will help unlock more wireless spectrum.

It’s a necessity as there is an increasing number of people who are

wirelessly connecting to the internet via smartphones, laptops, tablets,

and other wireless devices. This trial will open new doors to more

wireless coverage (especially in dead zones), Wi-Fi hotspots, and other

“wireless technologies”.

Wednesday, December 12. 2012

Via NewScientist

-----

The ethos of freedom from control that underpins the web is facing its first serious test, says Wendy M. Grossman

WHO runs the internet? For the past 30

years, pretty much no one. Some governments might call this a bug, but

to the engineers who designed the protocols, standards, naming and

numbering systems of the internet, it's a feature.

The goal was to build a network that

could withstand damage and would enable the sharing of information. In

that, they clearly succeeded - hence the oft-repeated line from John

Gilmore, founder of digital rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation:

"The internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around it."

These pioneers also created a robust platform on which a guy in a dorm

room could build a business that serves a billion people.

But perhaps not for much longer. This

week, 2000 people have gathered for the World Conference on

International Telecommunications (WCIT) in Dubai in the United Arab

Emirates to discuss, in part, whether they should be in charge.

The stated goal of the Dubai meeting

is to update the obscure International Telecommunications Regulations

(ITRs), last revised in 1988. These relate to the way international

telecom providers operate. In charge of this process is the

International Telecommunications Union (ITU), an agency set up in 1865

with the advent of the telegraph. Its $200 million annual budget is

mainly funded by membership fees from 193 countries and about 700

companies. Civil society groups are only represented if their

governments choose to include them in their delegations. Some do, some

don't. This is part of the controversy: the WCIT is effectively a closed

shop.

Vinton Cerf, Google's chief internet evangelist and co-inventor of the TCP/IP internet protocols, wrote in May that decisions in Dubai "have the potential to put government handcuffs on the net".

The need to update the ITRs isn't

surprising. Consider what has happened since 1988: the internet, Wi-Fi,

broadband, successive generations of mobile telephony, international

data centres, cloud computing. In 1988, there were a handful of

telephone companies - now there are thousands of relevant providers.

Controversy surrounding the WCIT

gathering has been building for months. In May, 30 digital and human

rights organisations from all over the world wrote to the ITU with three

demands: first, that it publicly release all preparatory documents and

proposals; second, that it open the process to civil society; and third

that it ask member states to solicit input from all interested groups at

national level. In June, two academics at George Mason University in

Virginia - Jerry Brito and Eli Dourado - set up the WCITLeaks site, soliciting copies of the WCIT documents and posting those they received. There were still gaps in late November when .nxt, a consultancy firm and ITU member, broke ranks and posted the lot on its own site.

The issue entered the mainstream when Greenpeace and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) launched the Stop the Net Grab

campaign, demanding that the WCIT be opened up to outsiders. At the

launch of the campaign on 12 November, Sharan Burrow, general secretary

of the ITUC, pledged to fight for as long it took to ensure an open

debate on whether regulation was necessary. "We will stay the distance,"

she said.

This marks the first time that such

large, experienced, international campaigners, whose primary work has

nothing to do with the internet, have sought to protect its freedoms.

This shows how fundamental a technology the internet has become.

A week later, the European parliament

passed a resolution stating that the ITU was "not the appropriate body

to assert regulatory authority over either internet governance or

internet traffic flows", opposing any efforts to extend the ITU's scope

and insisting that its human rights principles took precedence. The US

has always argued against regulation.

Efforts by ITU secretary general Hamadoun Touré to spread calm have largely failed. In October, he argued

that extending the internet to the two-thirds of the world currently

without access required the UN's leadership. Elsewhere, he has

repeatedly claimed that the more radical proposals on the table in Dubai

would not be passed because they would require consensus.

These proposals raise two key fears

for digital rights campaigners. The first concerns censorship and

surveillance: some nations, such as Russia, favour regulation as a way

to control or monitor content transiting their networks.

The second is financial. Traditional

international calls attract settlement fees, which are paid by the

operator in the originating country to the operator in the terminating

country for completing the call. On the internet, everyone simply pays

for their part of the network, and ISPs do not charge to carry each

other's traffic. These arrangements underpin network neutrality, the

principle that all packets are delivered equally on a "best efforts"

basis. Regulation to bring in settlement costs would end today's

free-for-all, in which anyone may set up a site without permission.

Small wonder that Google is one of the most vocal anti-WCIT campaigners.

How worried should we be? Well, the

ITU cannot enforce its decisions, but, as was pointed out at the Stop

the Net Grab launch, the system is so thoroughly interconnected that

there is plenty of scope for damage if a few countries decide to adopt

any new regulatory measures.

This is why so many people want to be

represented in a dull, lengthy process run by an organisation that may

be outdated to revise regulations that can be safely ignored. If you're

not in the room you can't stop the bad stuff.

Wendy M. Grossman is a science writer and the author of net.wars (NYU Press)

Friday, April 06. 2012

Via Vanity Fair

---

When the Internet was created, decades ago, one thing was inevitable:

the war today over how (or whether) to control it, and who should have

that power. Battle lines have been drawn between repressive regimes and

Western democracies, corporations and customers, hackers and law

enforcement. Looking toward a year-end negotiation in Dubai, where 193

nations will gather to revise a U.N. treaty concerning the Internet,

Michael Joseph Gross lays out the stakes in a conflict that could split

the virtual world as we know it.

Access to the full article @Vanity Fair

|