Entries tagged as computer

Friday, October 04. 2013

The First Carbon Nanotube Computer: The Hyper-Efficient Future Is Here

Via Gizmodo

-----

Coming just a year after the creation of the first carbon nanotube computer chip, scientists have just built the very first actual computer with a central processor centered entirely around carbon nanotubes. Which means the future of electronics just got tinier, more efficient, and a whole lot faster.

Built by a group of engineers at Stanford University, the computer itself is relatively basic compared to what we're used to today. In fact, according to Suhasish Mitra, an electrical engineer at Stanford and project co-leader, its capabilities are comparable to an Intel 4004—Intel's first microprocessor released in 1971. It can switch between basic tasks (like counting and organizing numbers) and send data back to an external memory, but that's pretty much it. Of course, the slowness is partially due to the fact the computer wasn't exactly built under the best conditions, MIT Technology Review explains:

"Don't let that fool you, though—this is just the first step. Last year, IBM proved that carbon nanotube transistors can run about three times as fast as the traditional silicon variety, and we'd already managed to arrange over 10,000 carbon nanotubes onto a single chip. They just hadn't connected them in a functioning circuit. But now that we have, the future is looking awfully bright."

Theoretically, carbon nanotube computing would be an order of magnitude faster that what we've seen thus far with any material. And since carbon nanotubes naturally dissipate heat at an incredible rate, computers made out of the stuff could hit blinding speeds without even breaking a sweat. So the speed limits we have using silicon—which doesn't do so well with heat—would be effectively obliterated.

The future of breakneck computing doesn't come without its little speedbumps, though. One of the problems with nanotubes is that they grow in a generally haphazard fashion, and some of them even come out with metallic properties, short-circuiting whatever transistor you decided to shove it in. In order to overcome these challenges, the researchers at Stanford had to use electricity to vaporize any metallic nanotubes that cropped up and formulated design algorithms that would be able to function regardless of any nanotube alignment problems. Now it's just a matter of scaling their lab-grown methods to an industrial level—easier said than done.

Still, despite the limitations at hand, this huge advancement just put another nail in silicon's ever-looming coffin.

Image: Norbert von der Groeben/Stanford

Friday, April 05. 2013

Computers Made Out of DNA, Slime and Other Strange Stuff

Via Wired

-----

Everybody knows a computer is a machine made of metal and plastic, with microchip cores turning streams of electrons into digital reality.

A century from now, though, computers could look quite different. They might be made from neurons and chemical baths, from bacterial colonies and pure light, unrecognizable to our old-fashioned 21st century eyes.

Far-fetched? A little bit. But a computer is just a tool for manipulating information. That's not a task wedded to some particular material form. After all, the first computers were people, and many people alive today knew a time when fingernail-sized transistors, each representing a single bit of information, were a great improvement on unreliable vacuum tubes.

On the following pages, Wired takes a look at some very non-traditional computers.

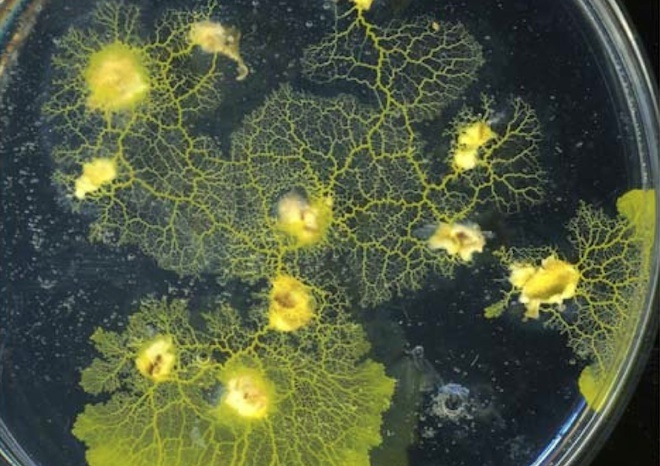

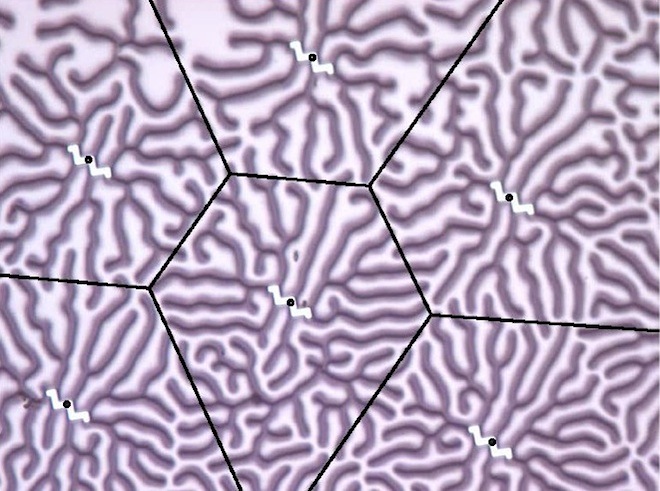

Above:Slime Computation

"The great appeal of non-traditional computing is that I can connect the un-connectable and link the un-linkable," said Andy Adamatzky, director of the Unconventional Computing Center at the University of the West of England. He's made computers from electrified liquid crystals, chemical goo and colliding particles, but is best known for his work with Physarum, the lowly slime mold.

Amoeba-like creatures that live in decaying logs and leaves, slime molds are, at different points in their lives, single-celled organisms or part of slug-like protoplasmic blobs made from the fusion of millions of individual cells. The latter form is assumed when slime molds search for food. In the process they perform surprisingly complicated feats of navigation and geometric problem-solving.

Slime molds are especially adept at finding solutions to tricky network problems, such as finding efficient designs for Spain's motorways and the Tokyo rail system. Adamatzky and colleagues plan to take this one step further: Their Physarum chip will be "a distributed biomorphic computing device built and operated by slime mold," they wrote in the project description.

"A living network of protoplasmic tubes acts as an active non-linear transducer of information, while templates of tubes coated with conductor act as fast information channels," describe the researchers. "Combined with conventional electronic components in a hybrid chip, Physarum networks will radically improve the performance of digital and analog circuits."

Image: Adamatzky et al./International Journal of General Systems

The Power of the Blob

Inspired by slime mold's problem-solving abilities, Adamatzky and Jeff Jones, also of the University of the West of England, programmed the rules for its behavior into a computational model of chemical attraction. That Russian nesting doll of emulations -- slime mold interpreted as a program embodied in chemistry translated into a program -- produced a series of experiments described in one superbly named paper: "Computation of the Travelling Salesman Problem by a Shrinking Blob."

In that paper, released March 25 on arXiv, Jones and Adamatzky's simulated chemical goo solves a classic, deceptively challenging mathematical problem, finding the shortest route between many points. For a few points this is simple, but many points become intractably difficult to compute -- but not for the blob (above).

Video: Jeff Jones and Andrew Adamatzky

Crystal Calculations

For decades, scientists who study strange materials known as complex fluids, which switch easily between different phases of matter, have been fascinated by the extraordinary geometries formed by liquid crystals at different temperatures and pressures.

Those geometries are stored information, and the interaction of crystals a form of computation. By running an electric current through a thin film (above) of liquid crystals, researchers led by Adamatzky were able to perform basic computational math and logic.

Image: Adamatzky et al./arXiv

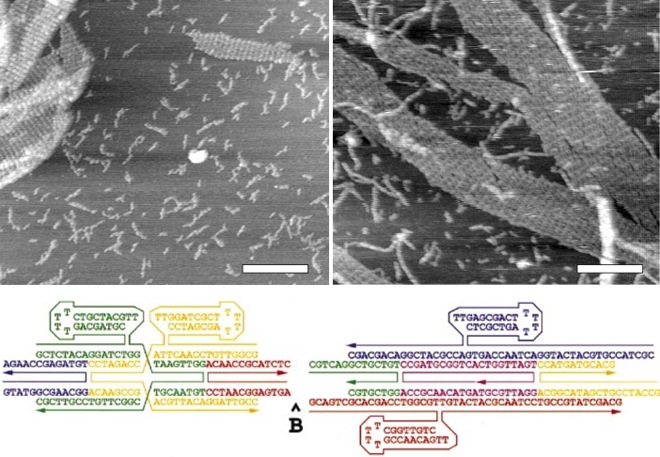

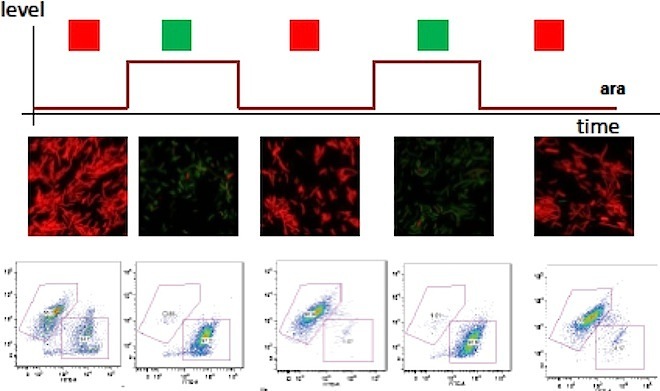

Computational DNA

It's hard to keep up with the accomplishments of synthetic biologists, who every week seem to announce some new method of turning life's building blocks into pieces for cellular computers. Yet even in this crowded field, last week's announcement by Stanford University researchers of a protein-based transistor stood out.

Responsible for conducting logic operations, the transistor, dubbed a "transcriptor," is the last of three components -- the others, already developed, are rewritable memory and information transmission -- necessary to program cells as computers. Synthetic biologist Drew Endy, the latest study's lead author, envisions plant-based environmental monitors, programmed tissues and even medical devices that "make Fantastic Voyage come true," he said.

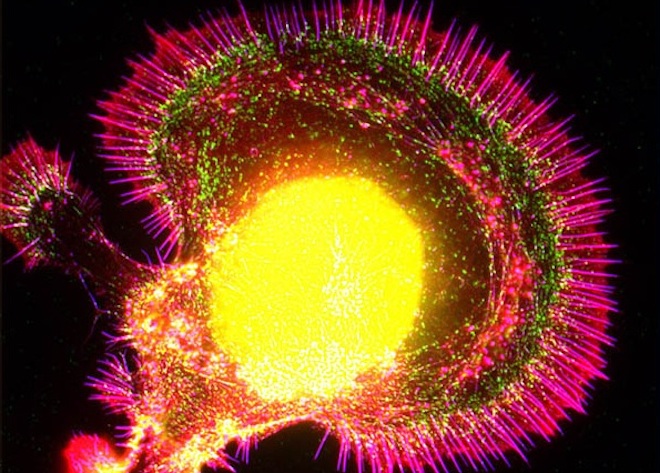

In the image above, Endy's cellular "buffer gates" flash red or yellow according to their informational state. In the image below, a string of DNA programmed by synthetic biologist Eric Winfree of the California Institute of Technology runs synthetic code -- the A's, C's, T's and G's -- with its molecules.

Image: Bonnet et al./Science

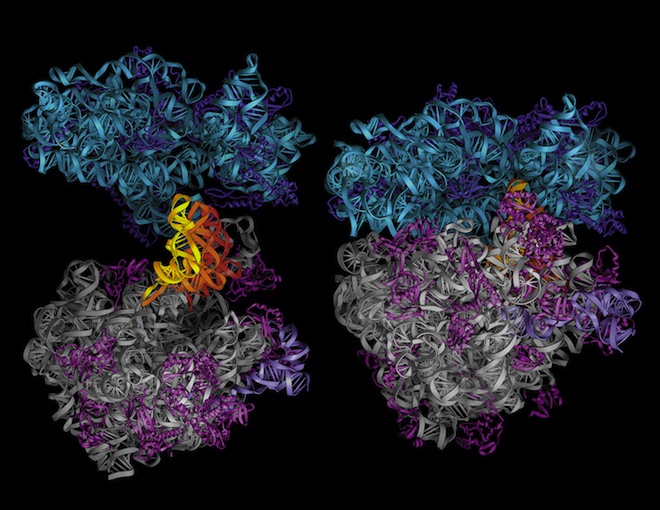

Evolution's Design

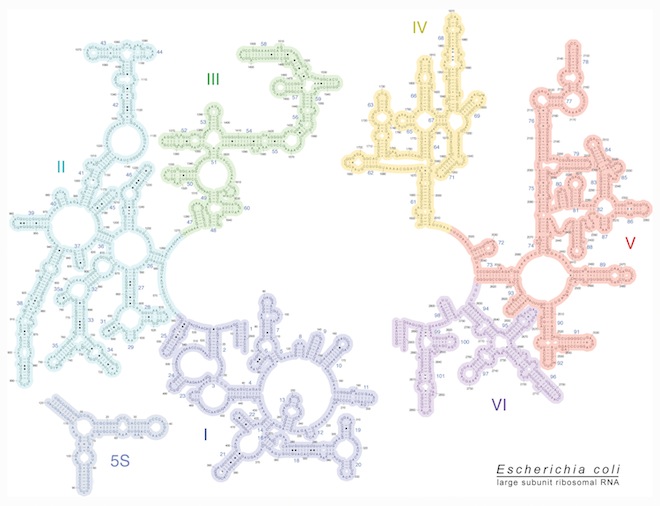

Most designs for molecular computers are based on human notions of what a computer should be. Yet as researchers applied mathematician Hajo Broersma of the Netherlands' University of Twente wrote of their work, "the simplest living systems have a complexity and sophistication that dwarfs manmade technology" -- and they weren't even designed to be that way. Evolution generated them.

In the NASCENCE project, short for "NAnoSCale Engineering for Novel Computation using Evolution," Broersma and colleagues plant to exploit evolution's ability to use combinations of molecules and their emergent properties in unexpected, incredibly powerful ways. They hope to develop a system that interfaces a digital computer with nano-scale particle networks, then use the computer to set algorithmic goals towards which evolution will guide the particles.

"We want to develop alternative approaches for situations or problems that are challenging or impossible to solve with conventional methods and models of computation," they write. One imagines computer chips with geometries typically seen in molecular structures, such as the E. coli ribosome and RNA seen here; success, predict Broersma's team, could lay "the foundations of the next industrial revolution."

Images: Center for Molecular Biology of RNA/University of California, Santa Cruz

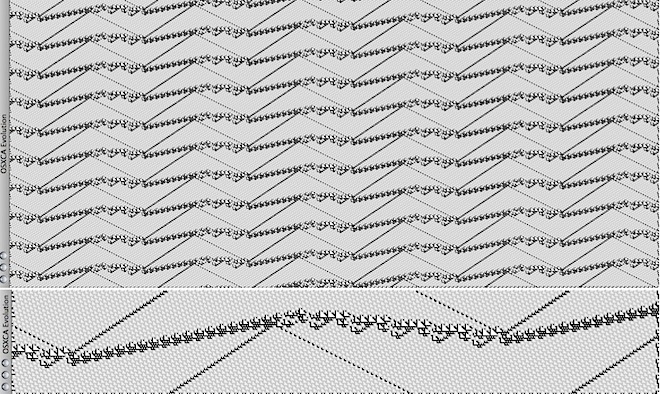

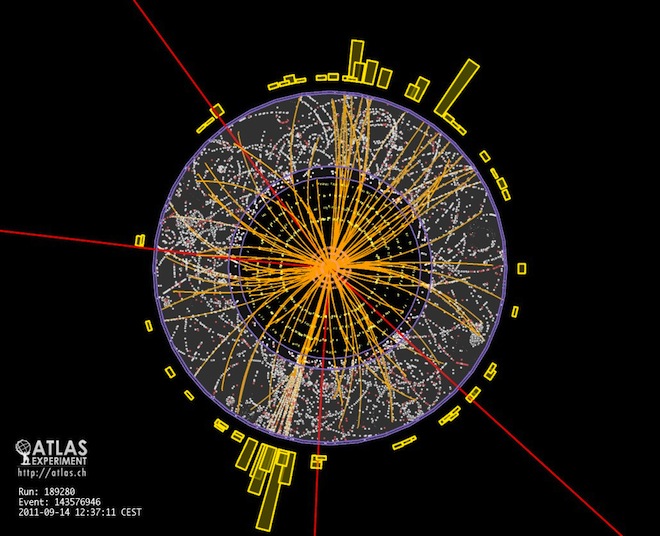

Particle Collisions

The Large Hadron Collider's 17 miles of track make it the world's largest particle accelerator. Could it also become the world's largest computer?

Not anytime soon, but it's at least possible to wonder. Another of Adamatzky's pursuits is what he calls "collision-based computing," in which computationally modeled particles course through a digital cyclotron, with their interactions used to carry out calculations. "Data and results are like balls travelling in an empty space," he said.

In the image below, simulated particle collisions evolve over time. Above, protons collide during the Large Hadron Collider's ATLAS experiment.

Images: 1) CERN 2) Martinez et al./A Computable Universe

Quantum Computers

The idea of computers that harness the spooky powers of quantum physics -- such as entanglement, in which far-flung particles are linked across space and time, so that altering one instantaneously affects the other -- has been around for years. And though quantum computers are still decades from reality, achievements keep piling up: entanglement made visible to the naked eye, performed with ever-greater numbers of particles, and used to control mechanical objects.

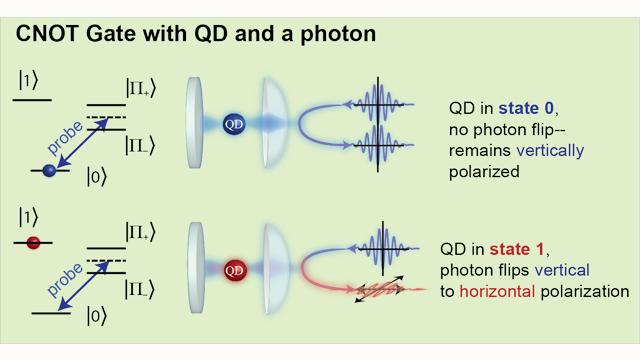

The latest achievement, described March 31 in Nature Photonics by physicist Edo Waks of the University of Maryland and colleagues, involves the control of photons with logic gates made with quantum dots, or crystal semiconductors controlled by lasers and magnetism. The results "represent an important step towards solid-state quantum networks," the researchers wrote.

Image: Schematic of the quantum dot-controlled photon. (Kim et al./Nature Photonics)

Frozen Light

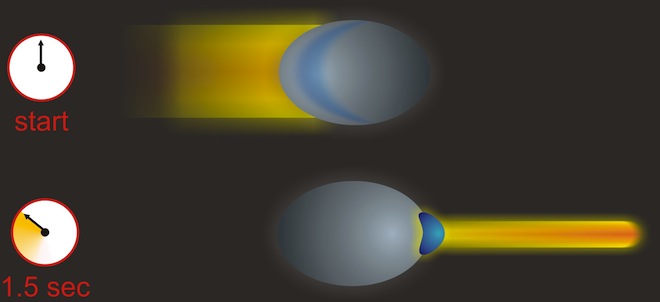

If quantum computers running on entangled photons are still far-off, there's another, non-quantum possibility for light-based computing. Clouds of ultra-cold atoms, frozen to temperatures just above absolute zero -- the point at which all motion ceases -- might be used to slow and control light, harnessing it inside an optical computer chip.

Image: Schematic of controlled light. (Anne Goodsell/Harvard University)

The Quantum Brain

It's easy to think of minds as computers, and accurate in the sense that brains are information-processing systems. They are also, however, exponentially more complex and sophisticated than any engineered device.

Even as quantum computing remains a far-off dream, some scientists think quantum physics underlies our thoughts. The question is far from settled, but quantum processes have been observed in a variety of non-human cells, raising the alluring possibility of a role in thought.

"Quantum computation occurs in the human mind, but only at the unconscious level," said theoretical physicist Paola Zizzi of Italy's University of Padua. "As quantum computation is much faster than classical computation, the unconscious thought is then much faster than the conscious thought and in a sense, it 'prepares' the latter."

If identified in our brains, quantum thinking could be used to inspire computer designs not yet dreamed of. Broadly speaking, that's a motivation of many in the non-conventional computing community, said Hector Zenil, a computer scientist at Sweden's Karolinska University and editor of A Computable Universe: Understanding and Exploring Nature as Computation.

Zenil isn't convinced by quantum claims for the brain, but he sees a world suffused by informational processes. Researchers like himself and Zizzi are trying to "use the computational principles that nature may use in order to conceive new kinds of computing," said Zenil.

Image: Sea slug neuron. (Dylan Burnette/Olympus Bioscapes)

Universe As Computer

In A Computable Universe, Zenil and others take the idea of computation as an abstract process, capable of being performed on any system that can store and manipulate information, to its logical extreme. Computers might not only be made from chemicals and cells and light, they say; the universe itself could be a computer, processing the information of which our everyday experiences -- and everything else -- are composed.

This is a tricky idea -- if the universe is computed, what's the computer? -- and for obvious reasons difficult to test, though Zenil thinks it's possible. In his work on the algorithmic aspects of existence, he's developed measures of the statistical distributions one would expect to see if reality is in fact computed.

If that seems a scary proposition, in which life would play out in linear mechanical ordination, rest assured: mechanistic, predetermined processes don't hold sway in a universal computer. Some aspects of existence will necessarily be "undecidable," impossible to describe with algorithms or predict beforehand. Ghosts will still live in the machine.

Image: The Milky Way galaxy/NASA/ESA/Q.D. Wang/Jet Propulsion Laboratory/S. Stolovy

Monday, November 26. 2012

Two-tonne Witch computer gets a reboot

Via BBC

-----

The machine cranked through the boring calculations atomic scientists once had to do

Kevin Murrell who discovered the computer explains how it was brought back to life

The world's oldest original working digital computer is going on display at The National Museum of Computing in Buckinghamshire.

The Witch, as the machine is known, has been restored to clattering and flashing life in a three-year effort.

In its heyday in the 1950s the machine was the workhorse of the UK's atomic energy research programme.

A happy accident led to its discovery in a municipal storeroom where it had languished for 15 years.

Cleaning upThe machine will make its official public debut at a special ceremony at The National Museum of Computing (TNMOC) in Bletchley Park on 20 November. Attending the unveiling will be some of its creators as well as staff that used it and students who cut their programming teeth on the machine.

Design and construction work on the machine began in 1949 and it was built to aid scientists working at the UK's Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell in Oxfordshire. The 2.5 tonne machine was created to ease the burden on scientists by doing electronically the calculations that previously were done using adding machines.

The machine first ran in 1951 and was known as the Harwell Dekatron - so named for the valves it used as a memory store. Although slow - the machine took up to 10 seconds to multiply two numbers - it proved very reliable and often cranked up 80 hours of running time in a week.

By 1957 the machine was being outstripped by faster, smaller computers and it was handed over to the Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Technical College (more recently Wolverhampton University) where it was used to teach programming and began to be called the Witch (Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computation from Harwell).

In 1973 it was donated to Birmingham's Museum of Science and Industry and was on show for 24 years until 1997 when the museum closed and the machine was dismantled and put into storage.

By chance Kevin Murrell, one of the TNMOC's trustees, spotted the control panel of the Witch in a photograph taken by another computer conservationist who had been in the municipal store seeking components for a different machine.

Mr Murrell said that as a "geeky teenager" he had regularly seen the Witch during many trips to the museum and instantly recognised its parts in the background of the photograph.

On subsequent trips to the storage facility the various parts of the Witch were found, retrieved and then taken to the museum at Bletchley where restoration began.

The restoration effort was led by conservationist Delwyn Holroyd who said it was "pretty dirty" when the machine first arrived at Bletchley. Remarkably, he said, it had not suffered too much physical damage and the restoration team has been at pains to replace as little as possible. The vast majority of the parts on the machine, including its 480 relays and 828 Dekatron tubes, are entirely original, he said.

Said Mr Murrell: "It's important for us to have a machine like this back in working order as it gives us an understanding of the state of technology in the late 1940s in Britain."

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131054)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101667)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100065)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57896)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57461)

Categories

Show tagged entries

Syndicate This Blog

Calendar

|

|

February '26 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |