Wednesday, June 27. 2012

Cycles, Cells and Platters: An Empirical Analysis of Hardware Failures on a Million Consumer PCs

-----

Abstract:

We present the first large-scale analysis of hardware failure rates on a million consumer PCs. We find that many failures are neither transient nor independent. Instead, a large portion of hardware induced failures are recurrent: a machine that crashes from a fault in hardware is up to two orders of magnitude more likely to crash a second time. For example, machines with at least 30 days of accumulated CPU time over an 8 month period had a 1 in 190 chance of crashing due to a CPU subsystem fault. Further, machines that crashed once had a probability of 1 in 3.3 of crashing a second time. Our study examines failures due to faults within the CPU, DRAMand disk subsystems. Our analysis spans desktops and laptops, CPU vendor, overclocking, underclocking, generic vs. brand name, and characteristics such as machine speed and calendar age. Among our many results, we find that CPU fault rates are correlated with the number of cycles executed, underclocked machines are significantly more reliable than machines running at their rated speed, and laptops are more reliable than desktops.

Wednesday, June 20. 2012

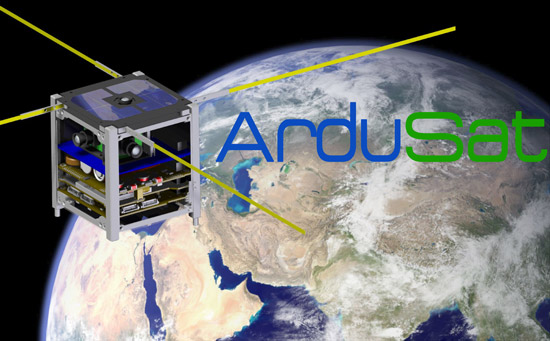

ArduSat: a real satellite mission that you can be a part of

Via DVICE

-----

We've been writing a lot recently about how the private space industry is poised to make space cheaper and more accessible. But in general, this is for outfits such as NASA, not people like you and me.

Today, a company called NanoSatisfi is launching a Kickstarter project to send an Arduino-powered satellite into space, and you can send an experiment along with it.

Whether it's private industry or NASA or the ESA or anyone else, sending stuff into space is expensive. It also tends to take approximately forever to go from having an idea to getting funding to designing the hardware to building it to actually launching something. NanoSatisfi, a tech startup based out of NASA's Ames Research Center here in Silicon Valley, is trying to change all of that (all of it) by designing a satellite made almost entirely of off-the-shelf (or slightly modified) hobby-grade hardware, launching it quickly, and then using Kickstarter to give you a way to get directly involved.

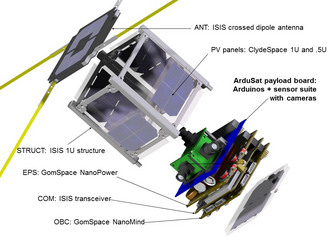

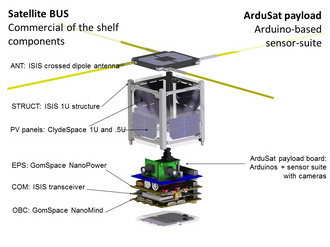

ArduSat is based on the CubeSat platform, a standardized satellite framework that measures about four inches on a side and weighs under three pounds. It's just about as small and cheap as you can get when it comes to launching something into orbit, and while it seems like a very small package, NanoSatisfi is going to cram as much science into that little cube as it possibly can.

Here's the plan: ArduSat, as its name implies, will run on Arduino boards, which are open-source microcontrollers that have become wildly popular with hobbyists. They're inexpensive, reliable, and packed with features. ArduSat will be packing between five and ten individual Arduino boards, but more on that later. Along with the boards, there will be sensors. Lots of sensors, probably 25 (or more), all compatible with the Arduinos and all very tiny and inexpensive. Here's a sampling:

Yeah, so that's a lot of potential for science, but the entire Arduino sensor suite is only going to cost about $1,500. The rest of the satellite (the power system, control system, communications system, solar panels, antennae, etc.) will run about $50,000, with the launch itself costing about $35,000. This is where you come in.

NanoSatisfi is looking for Kickstarter funding to pay for just the launch of the satellite itself: the funding goal is $35,000. Thanks to some outside investment, it's able to cover the rest of the cost itself. And in return for your help, NanoSatisfi is offering you a chance to use ArduSat for your own experiments in space, which has to be one of the coolest Kickstarter rewards ever.

- For a $150 pledge, you can reserve 15 imaging slots on ArduSat. You'll be able to go to a website, see the path that the satellite will be taking over the ground, and then select the targets you want to image. Those commands will be uploaded to the ArduSat, and when it's in the right spot in its orbit, it'll point its camera down at Earth and take a picture which will be then emailed right to you. From space.

- For $300, you can upload your own personal message to ArduSat, where it will be broadcast back to Earth from space for an entire day. ArduSat is in a polar orbit, so over the course of that day, it'll circle the Earth seven times and your message will be broadcast over the entire globe.

- For $500, you can take advantage of the whole point of ArduSat and run your very own experiment for an entire week on a selection of ArduSat's sensors. You know, in space. Just to be clear, it's not like you're just having your experiment run on data that's coming back to Earth from the satellite. Rather, your experiment is uploaded to the satellite itself, and it's actually running on one of the Arduino boards on ArduSat real time, which is why there are so many identical boards packed in there.

Now, NanoSatisfi itself doesn't really expect to get involved with a lot of the actual experiments that the ArduSat does: rather, it's saying "here's this hardware platform we've got up in space, it's got all these sensors, go do cool stuff." And if the stuff that you can do with the existing sensor package isn't cool enough for you, backers of the project will be able to suggest new sensors and new configurations, even for the very first generation ArduSat.

To make sure you don't brick the satellite with buggy code, NanSatisfi will have a duplicate satellite in a space-like environment here on Earth that it'll use to test out your experiment first. If everything checks out, your code gets uploaded to the satellite, runs in whatever timeslot you've picked, and then the results get sent back to you after your experiment is completed. Basically, you're renting time and hardware on this satellite up in space, and you can do (almost) whatever you want with that.

ArduSat has a lifetime of anywhere from six months to two years. None of this payload stuff (neither the sensors nor the Arduinos) are specifically space-rated or radiation-hardened or anything like that, and some of them will be exposed directly to space. There will be some backups and redundancy, but partly, this will be a learning experience to see what works and what doesn't. The next generation of ArduSat will take all of this knowledge and put it to good use making a more capable and more reliable satellite.

This, really, is part of the appeal of ArduSat: with a fast,

efficient, and (relatively) inexpensive crowd-sourced model, there's a

huge potential for improvement and growth. For example, If this

Kickstarter goes bananas and NanoSatisfi runs out of room for people to

get involved on ArduSat, no problem, it can just build and launch

another ArduSat along with the first, jammed full of (say) fifty more

Arduinos so that fifty more experiments can be run at the same time. Or

it can launch five more ArduSats. Or ten more. From the decision to

start developing a new ArduSat to the actual launch of that ArduSat is a

period of just a few months. If enough of them get up there at the same

time, there's potential for networking multiple ArduSats together up in

space and even creating a cheap and accessible global satellite array.

If this sounds like a lot of space junk in the making, don't worry: the

ArduSats are set up in orbits that degrade after a year or two, at which

point they'll harmlessly burn up in the atmosphere. And you can totally

rent the time slot corresponding with this occurrence and measure

exactly what happens to the poor little satellite as it fries itself to a

crisp.

Longer term, there's also potential for making larger ArduSats with more complex and specialized instrumentation. Take ArduSat's camera: being a little tiny satellite, it only has a little tiny camera, meaning that you won't get much more detail than a few kilometers per pixel. In the future, though, NanoSatisfi hopes to boost that to 50 meters (or better) per pixel using a double or triple-sized satellite that it'll call OptiSat. OptiSat will just have a giant camera or two, and in addition to taking high resolution pictures of Earth, it'll also be able to be turned around to take pictures of other stuff out in space. It's not going to be the next Hubble, but remember, it'll be under your control.

NanoSatisfi's Peter Platzer holds a prototype ArduSat board,

including the master controller, sensor suite, and camera. Photo: Evan

Ackerman/DVICE

Assuming the Kickstarter campaign goes well, NanoSatisfi hopes to complete construction and integration of ArduSat by about the end of the year, and launch it during the first half of 2013. If you don't manage to get in on the Kickstarter, don't worry- NanoSatisfi hopes that there will be many more ArduSats with many more opportunities for people to participate in the idea. Having said that, you should totally get involved right now: there's no cheaper or better way to start doing a little bit of space exploration of your very own.

Check out the ArduSat Kickstarter video below, and head on through the link to reserve your spot on the satellite.

-----

Wednesday, June 13. 2012

Three-Minute Tech: Tegra 3

Via Tech Hive

-----

If you follow the world of Android tablets and phones, you may have heard a lot about Tegra 3 over the last year. Nvidia's chip currently powers many of the top Android tablets, and should be found in a few Android smartphones by the end of the year. It may even form the foundation of several upcoming Windows 8 tablets and possibly future phones running Windows Phone 8. So what is the Tegra 3 chip, and why should you care whether or not your phone or tablet is powered by one?

Nvidia's system-on-chip

Tegra is the brand for Nvidia's line of system-on-chip (SoC) products for phones, tablets, media players, automobiles, and so on. What's a system-on-chip? Essentially, it's a single chip that combines all the major functions needed for a complete computing system: CPU cores, graphics, media encoding and decoding, input-output, and even cellular or Wi-Fi communcations and radios. The Tegra series competes with chips like Qualcomm's Snapdragon, Texas Instruments' OMAP, and Samsung's Exynos.

The first Tegra chip was a flop. It was used in very few products, notably the ill-fated Zune HD and Kin smartphones from Microsoft. Tegra 2, an improved dual-core processor, was far more successful but still never featured in enough devices to become a runaway hit.

Tegra 3 has been quite the success so far. It is found in a number of popular Android tablets like the Eee Pad Transformer Prime, and is starting to find its way into high-end phones like the global version of the HTC One X (the North American version uses a dual-core Snapdragon S4 instead, as Tegra 3 had not been qualified to work with LTE modems yet). Expect to see it in more Android phones and tablets internationally this fall.

4 + 1 cores

Tegra 3 is based on the ARM processor design and architecture, as are most phone and tablet chips today. There are many competing ARM-based SoCs, but Tegra 3 was one of the first to include four processor cores. There are now other quad-core SoCs from Texas Instruments and Samsung, but Nvidia's has a unique defining feature: a fifth low-power core.

All five of the processor cores are based on the ARM Cortex-A9 design, but the fifth core is made using a special low-power process that sips battery at low speeds, but doesn't scale up to high speeds very well. It is limited to only 500MHz, while the other cores run up to 1.4GHz (or 1.5GHz in single-core mode).

When your phone or tablet is in sleep mode, or you're just performing very simple operations or using very basic apps, like the music player, Tegra 3 shuts down its four high-power cores and uses only the low-power core. It's hard to say if this makes it far more efficient than other ARM SoCs, but battery life on some Tegra 3 tablets has been quite good.

Good, not great, graphics

Nvidia's heritage is in graphics processors. The company's claim to fame has been its GPUs for traditional laptops, desktops, and servers. You might expect Tegra 3 to have the best graphics processing power of any tablet or phone chip, but that doesn't appear to be the case. Direct graphics comparisons can be difficult, but there's a good case to be made that the A5X processor in the new iPad has a far more powerful graphics processor. Still, Tegra 3 has plenty of graphics power, and Nvidia works closely with game developers to help them optimize their software for the platform. Tegra 3 supports high-res display output (up to 2560 x 1600) and improved video decoding capabilities compared to earlier Tegra chips.

Do you need one?

The million-dollar question is: Does the Tegra 3 chip provide a truly better experience than other SoCs? Do you need four cores, or even "4 + 1"? The answer is no. Most smartphone and tablet apps don't make great use of multiple CPU cores, and making each core faster can often do more for the user experience than adding more cores. That said, you shouldn't avoid a product because it has a Tegra 3 chip, either. Its performance and battery life appear to be quite competitive in today's tablet and phone market. Increasingly, the overall quality of a product is determined by its design, size, weight, display quality, camera quality, and other features more than mere processor performance. Consider PCWorld's review of the North American HTC One X; with the dual-core Snapdragon S4 instead of Tegra 3, performance was still very impressive.

Wednesday, June 06. 2012

The Mechanics and Meaning of That Ol' Dial-Up Modem Sound

Via The Atlantic

By Alexis Madrigal

-----

Pshhhkkkkkkrrrrkakingkakingkakingtshchchchchchchchcch*ding*ding*ding"

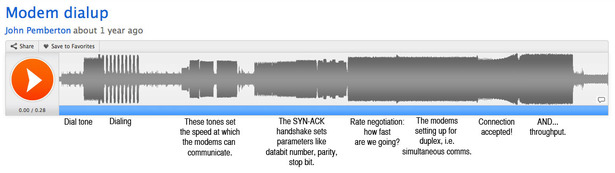

Modem dialup by John Pemberton

Of all the noises that my children will not understand, the one that is nearest to my heart is not from a song or a television show or a jingle. It's the sound of a modem connecting with another modem across the repurposed telephone infrastructure. It was the noise of being part of the beginning of the Internet.

I heard that sound again this week on Brendan Chillcut's simple and wondrous site: The Museum of Endangered Sounds. It takes technological objects and lets you relive the noises they made: Tetris, the Windows 95 startup chime, that Nokia ringtone, television static. The site archives not just the intentional sounds -- ringtones, etc -- but the incidental ones, like the mechanical noise a VHS tape made when it entered the VCR or the way a portable CD player sounded when it skipped. If you grew up at a certain time, these sounds are like technoaural nostalgia whippets. One minute, you're browsing the Internet in 2012, the next you're on a bus headed up I-5 to an 8th grade football game against Castle Rock in 1995.

The noises our technologies make, as much as any music, are the soundtrack to an era. Soundscapes are not static; completely new sets of frequencies arrive, old things go. Locomotives rumbled their way through the landscapes of 19th century New England, interrupting Nathaniel Hawthorne-types' reveries in Sleepy Hollows. A city used to be synonymous with the sound of horse hooves and the clatter of carriages on the stone streets. Imagine the people who first heard the clicks of a bike wheel or the vroom of a car engine. It's no accident that early films featuring industrial work often include shots of steam whistles, even though in many (say, Metropolis) we can't hear that whistle.

When I think of 2012, I will think of the overworked fan of my laptop and the ding of getting a text message on my iPhone. I will think of the beep of the FastTrak in my car as it debits my credit card so I can pass through a toll onto the Golden Gate Bridge. I will think of Siri's uncanny valley voice.

But to me, all of those sounds -- as symbols of the era in which I've come up -- remain secondary to the hissing and crackling of the modem handshake. I first heard that sound as a nine-year-old. To this day, I can't remember how I figured out how to dial the modem of our old Zenith. Even more mysterious is how I found the BBS number to call or even knew what a BBS was. But I did. BBS were dial-in communities, kind of like a local AOL. You could post messages and play games, even chat with people on the bigger BBSs. It was personal: sometimes, you'd be the only person connected to that community. Other times, there'd be one other person, who was almost definitely within your local prefix.

When we moved to Ridgefield, which sits outside Portland, Oregon, I had a summer with no friends and no school: The telephone wire became a lifeline. I discovered Country Computing, a BBS I've eulogized before, located in a town a few miles from mine. The rural Washington BBS world was weird and fun, filled with old ham-radio operators and computer nerds. After my parents' closed up shop for the work day, their "fax line" became my modem line, and I called across the I-5 to play games and then, slowly, to participate in the nascent community.

In the beginning of those sessions, there was the sound, and the sound was data.

Fascinatingly, there's no good guide to the what the beeps and hisses represent that I could find on the Internet. For one, few people care about the technical details of 1997's hottest 56k modems. And for another, whatever good information exists out there predates the popular explosion of the web and the all-knowing Google.

So, I asked on Twitter and was rewarded with an accessible and elegant explanation from another user whose nom-de-plume is Miso Susanowa. (Susanowa used to run a BBS.) I transformed it into the annotated graphic below, which explains the modem sound part-by-part. (You can click it to make it bigger.)

This is a choreographed sequence that allowed these digital devices to

piggyback on an analog telephone network. "A phone line carries only the small range of frequencies in

which most human conversation takes place: about 300 to 3,300 hertz," Glenn Fleishman explained in the Times back in 1998. "The

modem works within these limits in creating sound waves to carry data

across phone lines." What you're hearing is the way 20th century technology tunneled through a 19th century network;

what you're hearing is how a network designed to send the noises made

by your muscles as they pushed around air came to transmit anything, or

the almost-anything that can be coded in 0s and 1s.

The frequencies of the modem's sounds represent parameters for further communication. In the early going, for example, the modem that's been dialed up will play a note that says, "I can go this fast." As a wonderful old 1997 website explained, "Depending on the speed the modem is trying to talk at, this tone will have a different pitch."

That is to say, the sounds weren't a sign that data was being

transferred: they were the data being transferred. This noise was the

analog world being bridged by the digital. If you are old enough to

remember it, you still knew a world that was analog-first.

Long before I actually had this answer in hand, I could sense that the patterns of the beats and noise meant something. The sound would move me, my head nodding to the beeps that followed the initial connection. You could feel two things trying to come into sync: Were they computers or me and my version of the world?

As I learned again today, as I learn every day, the answer is both.

Monday, June 04. 2012

Invasion of the Tiny, Linux-Powered PCs

Via LinuxInsider

-----

Bigger may be better if you're from Texas, but it's becoming increasingly clear to the rest of us that it really is a small world after all.

Case in point? None other than what one might reasonably call the invasion of tiny Linux PCs going on all around us.

We've got the Raspberry Pi, we've got the Cotton Candy. Add to those the Mele A1000, the VIA APC, the MK802 and more, and it's becoming increasingly difficult not to compute like a Lilliputian.

Where's it all going? That's what Linux bloggers have been pondering in recent days. Down at the seedy Broken Windows Lounge the other night, Linux Girl got an earful.

It's 'Fantastic'

"Linux has been heading towards one place for many years now: complete and total world domination!" quipped Thoughts on Technology blogger and Bodhi Linux lead developer Jeff Hoogland.

"All joking aside, these new devices simply further showcase Linux's unmatched ability to be flexible across an array of different devices of all sizes and power," Hoogland added.

"Having a slew of devices that are powerful enough for users to browse the web -- which, let's be honest, is all a good deal of people do these days -- for under 100 USD is fantastic," he concluded.

'It Only Gets More Exciting'

Similarly, "I believe that the medley of tiny Linux PCs we're seeing hitting the market lately is the true sign of the Post PC Era," suggested Google+ blogger Linux Rants.

"The smartphone started it, but the Post PC Era will begin in earnest when the functionality that we currently see in the home computer is replaced by numerous small appliance-type devices," Linux Rants explained. "These tiny Linux PCs are the harbinger of those appliances -- small, low-cost, programmable devices that can be made into virtually anything the owner desires."

Other devices we're already seeing include "the oven that you can

turn on with a text message, the espresso machine that you can control

with a text message, home security ![]() systems and cars that can be controlled from your smartphone," he

added. "This is where the Post PC Era begins, and it only gets more

exciting from here."

systems and cars that can be controlled from your smartphone," he

added. "This is where the Post PC Era begins, and it only gets more

exciting from here."

'There Is No Reason Not to Do It'

This is "definitely the wave of the future," agreed Google+ blogger Kevin O'Brien.

"Devices of all kinds are getting smaller and smaller, while simultaneously increasing their power," O'Brien explained. "Exponential growth does that over time.

"My phone in my pocket right now has more computing power than the rockets that went to the moon," he added. "And if you look ahead, a few more turns of exponential growth means we'll have the equivalent of a full desktop computer the size of an SD card within a few years."

At that point, "everything starts to be computerized, because adding a little intelligence is so cheap there is no reason not to do it," O'Brien concluded.

'We're Approaching That Future'

Indeed, "many including myself have long been harping on the fact that today's computers are orders of magnitude faster than early systems on which we ran graphic interfaces and got work done, and yet are dismissed as toys," Hyperlogos blogger Martin Espinoza told Linux Girl.

"A friend suggested to me once that eventually microwave ovens would contain little Unix servers 'on a chip' because that would be basically all you could get, because it would actually be cheaperto use such a system when given the cost of developing an alternative," he said. "Seeing the cost of these new products it looks to me like we're approaching that future rapidly.

"There has always been demand for low-cost computers, and the massive proliferation of low-cost, low-power cores has pushed their price down to the point where we can finally have them," Espinoza concluded.

"Even adjusted for inflation," he said, "many of these computers are an order of magnitude cheaper than the cheapest useful home computers from the time when personal computing began to gain popularity, and yet they are certainly powerful enough to serve many roles including many people's main or even only 'computer.'"

'It Gives Me Hope'

Consultant and Slashdot blogger Gerhard Mack was similarly enthusiastic.

"I love it," Mack told Linux Girl.

"When I was a child, my parents brought home all sorts of fun things to tinker with, and I learned while doing it," he explained. "But these last few years it seems like the learning electronics and their equivalents have disappeared into a mass of products that are only for what the manufacturer designed them for and nothing else.

"I am loving the return of my ability to tinker," Mack concluded. "It gives me hope that there can be a next generation of kids who can love the enjoyment of simply creating things."

'They Look a Bit Expensive'

Not everyone was thrilled, however.

"Okay, I am not all that excited about the invasion of the tiny PC," admitted Roberto Lim, a lawyer and blogger on Mobile Raptor.

"With 7-inch Android tablets with capacitive displays, running Android 4.0 and with access to Google (Nasdaq: GOOG) Play's Android app market, 8 GB or storage expandable via a Micro SD card, 1080p video playback, a USB port and HDMI out and 3000 to 4000 mAh batteries starting at US$90, it is a bit hard to get excited about these tiny PCs," Lim explained.

"Despite the low prices of the tiny PCs, they all look a bit expensive when compared to what is already in the market," he opined.

'These Devices Have a Niche'

The category really isn't even all that new, Slashdot blogger hairyfeet opined.

"There have been mini ARM-based Linux boxes for several years now," he explained. "From portable media players to routers to set-top boxes, there are a ton of little bitty boxes running embedded Linux."

It's not even quite right to call such devices PCs "because PC has an already well-defined meaning: it was originally 'IBM PC compatible,'" hairyfeet added. "Even if you give them the benefit of the doubt, PCs have always been general use computers, and these things are FAR from general use."

Rather, "they are designed with a very specific and narrow job in mind," he said. "Trying to use them as general computers would just be painful."

So, "in the end these devices have a niche, just as routers and beagleboards and the pi does, but that niche is NOT general purpose in any way, shape, or form," hairyfeet concluded.

'Opportunities for Specialists'

Chris Travers, a Slashdot blogger who works on the Ledger SMB project, considered the question through the lens of evolutionary ecology.

"In any ecological system an expanding niche allows for differentiation, and a contracting niche requires specialization," Travers pointed out. 'So, for example, if a species of moth undergoes a population explosion, predators of that moth will often specialize and be more picky as to what prey they go after."

The same thing happens with markets, Travers suggested.

"When a market expands, it provides opportunities for specialists, but when it contracts, only the generalists can survive," he told Linux Girl.

'Niche Environments'

The tiny new devices are "replacements for desktop and laptop systems in niche environments," Travers opined.

"In many environments these may be far more capable than traditional systems," he added.

The bottom line, though, "is that the Linux market is growing at a healthy rate," Travers concluded.

'The Right Way to Do IT'

"Moore's Law allows the world to do more with less hardware and so does FLOSS," blogger Robert Pogson told Linux Girl. "It's the right way to do IT rather than paying a bunch for the privilege of running the hardware we own."

Last year was a turning point, Pogson added.

"More people bought small, cheap computers running Linux than that other OS, and the world saw that things were fine without Wintel," he explained. "2012 will bring more of the same." By the end of this year, in fact, "the use of GNU/Linux on small cheap computers doing what we used to do with huge hair-drying Wintel PCs will be mainstream in many places on Earth," Pogson predicted. "In 2012 we will see a major decline in the number of PCs running that other OS. We will see major shelf-space given to Linux PCs at retail."

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131047)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101657)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100057)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57886)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57448)