Illustration: dzima1/Getty

When Google chief financial officer Patrick Pichette said the tech giant might bring 10 gigabits per second internet connections

to American homes, it seemed like science fiction. That’s about 1,000

times faster than today’s home connections. But for NASA, it’s downright

slow.

While the rest of us send data across the public internet, the space agency uses a shadow network called ESnet, short for Energy Science Network, a set of private pipes that has demonstrated cross-country data transfers of 91 gigabits per second–the fastest of its type ever reported.

NASA isn’t going bring these speeds to homes, but it is using this

super-fast networking technology to explore the next wave of computing

applications. ESnet, which is run by the U.S. Department of Energy, is

an important tool for researchers who deal in massive amounts of data

generated by projects such as the Large Hadron Collider and the Human

Genome Project. Rather sending hard disks back and forth through the

mail, they can trade data via the ultra-fast network. “Our vision for

the world is that scientific discovery shouldn’t be constrained by

geography,” says ESnet director Gregory Bell.

In making its network as fast as it can possibly be, ESnet and

researchers are organizations like NASA are field testing networking

technologies that may eventually find their way into the commercial

internet. In short, ESnet a window into what our computing world will

eventually look like.

The Other Net

The first nationwide computer research network was the Defense

Department’s ARPAnet, which evolved into the modern internet. But it

wasn’t the last network of its kind. In 1976, the Department of Energy

sponsored the creation of the Magnetic Fusion Energy Network to connect

what is today the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center

with other research laboratories. Then the agency created a second

network in 1980 called the High Energy Physics Network to connect

particle physics researchers at national labs. As networking became more

important, agency chiefs realized it didn’t make sense to maintain

multiple networks and merged the two into one: ESnet.

The nature of the network changes with the times. In the early days

it ran on land lines and satellite links. Today it is uses fiber optic

lines, spanning the DOE’s 17 national laboratories and many other sites,

such as university research labs. Since 2010, ESnet and Internet2—a

non-profit international network built in 1995 for researchers after the

internet was commercialized—have been leasing “dark fiber,” the excess

network capacity built-up by commercial internet providers during the

late 1990s internet bubble.

An Internet Fast Lane

In November, using this network, NASA’s High End Computer Networking

team achieved its 91 gigabit transfer between Denver and NASA Goddard

Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. It was the fastest

end-to-end data transfer ever conducted under “real world” conditions.

ESnet has long been capable of 100 gigabit transfers, at least in

theory. Network equipment companies have been offering 100 gigabit

switches since 2010. But in practice, long-distance transfers were much

slower. That’s because data doesn’t travel through the internet in a

straight line. It’s less like a super highway and more like an

interstate highway system. If you wanted to drive from San Francisco to

New York, you’d pass through multiple cities along the way as you

transferred between different stretches of highway. Likewise, to send a

file from San Francisco to New York on the internet—or over ESnet—the

data will flow through hardware housed in cities across the country.

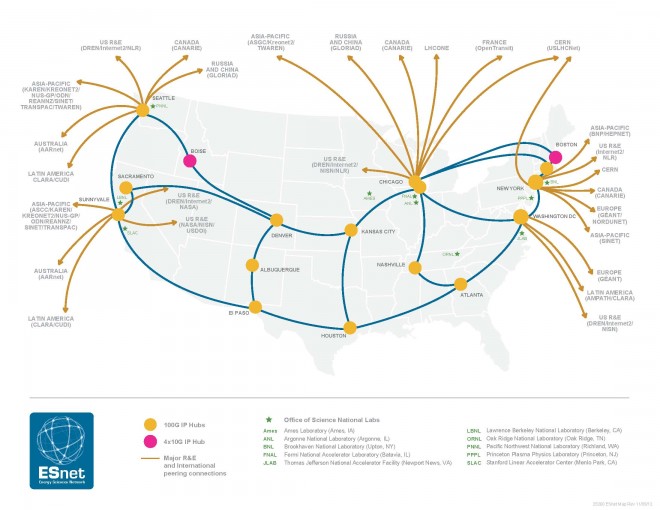

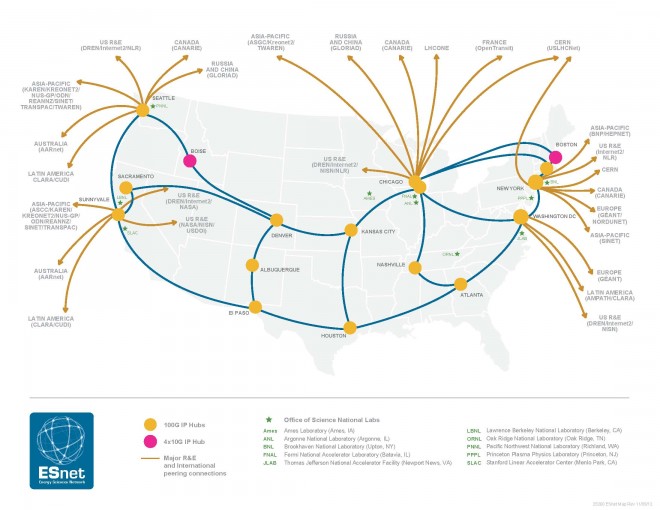

A map of ESnet’s connected sites. Image: Courtesy of ESnet

NASA did a 98 gigabit transfer between Goddard and the University of Utah over ESnet in 2012. And Alcatel-Lucent and BT obliterated that record

earlier this year with a 1.4 terabit connection between London and

Ipswich. But in both cases, the two locations had a direct connection,

something you rarely see in real world connections.

On the internet and ESnet, every stop along the way creates the

potential for a bottleneck, and every piece of gear must be ready to

handle full 100 gigabit speeds. In November, the team finally made it

work. “This demonstration was about using commercial, off-the-shelf

technology and being able to sustain the transfer of a large data

network,” says Tony Celeste, a sales director at Brocade, the company

that manufactured the equipment used in the record-breaking test.

Experiments for the Future

Meanwhile, the network is advancing the state of the art in other

ways. Researchers have used it to explore virtual network circuits

called “OSCARS,”

which can be used to create complex networks without complex hardware

changes. And they’re working on what are known as network “DMZs,” which can achieve unusually fast speeds by handling security without traditional network firewalls.

These solutions are designed specifically for networks in which a

small number of very large transfers take place–as opposed to the

commercial internet where lots of small transfers take place. But

there’s still plenty for commercial internet companies to learn from

ESnet. Telecommunications company XO Communications already has a 100 gigabit backbone, and we can expect more companies to follow suit.

Although we won’t see 10-gigabit connections—let alone 100 gigabit

connections—at home any time soon, higher capacity internet backbones

will mean less congestion as more and more people stream high-definition

video and download ever-larger files. And ESnet isn’t stopping there.

Bell says the organization is already working on a 400 gigabit network,

and the long-term goal is a terabyte per second network, which about

100,000 times faster than today’s home connections. Now that sounds like

science fiction.

Update 13:40 EST 06/17/14: This story has been updated to make it clear that ESnet is run by the Department of Energy.

Update 4:40 PM EST 06/17/14: This story has been updated to avoid

confusion between ESnet’s production network and its more experimental

test bed network.