The story of Apple’s iPad is incredible, especially considering how young the device is. Released in April of 2010, the iPad has redefined and dominated the tablet market (if there even is a tablet market) and spawned a radical change in how tablet devices look and operate.

Of course, Apple didn’t cut the iPad from whole cloth (which probably would have been linen). It was built upon decades of ideas, tests, products and more ideas. Before we explore the iPad’s story, it’s appropriate to consider the tablets and the pen-driven devices that preceded it.

So Popular So Quickly

Today the iPad is so popular that it’s easy to overlook that it’s only three years old. Apple has updated it just twice. Here’s a little perspective to reinforce the iPad’s tender age:

- When J. K. Rowling published Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, there was no iPad.

- When President Barak Obama was inaugurated as America’s 44th president, there was no iPad.

- In 2004 when the Boston Red Sox broke the Curse of the Bambino and won the World Series for the first time in 86 years, there was no iPad. Nor did it exist three years later, when they won the championship again.

Elisha Gray and the Telautograph

Elisha Gray was an electrical engineer and inventor who lived in Ohio and Massachusetts between 1835 and 1901. Elisha was a wonderful little geek, and became interested in electricity while studying at Oberlin College. He collected nearly 70 patents in his lifetime, including that of the Telautograph. [PDF].

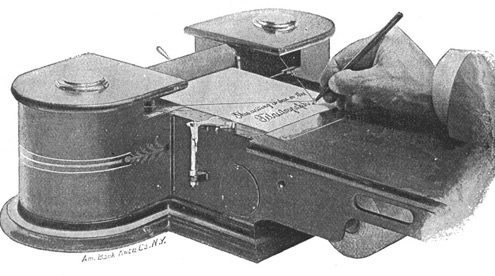

The Telautograph let a person use a stylus that was connected to two rheostats, which managed the current produced by the amount of resistance generated as the operator wrote with the stylus. That electronic record was transmitted to a second Telautograph, reproducing the author’s writing on a scroll of paper. Mostly. Gray noted that, since the scroll of paper was moving, certain letters were difficult or impossible to produce. For example, you couldn’t “…dot an i or cross a t or underscore or erase a word.” Users had to get creative.

Still, the thing was a hit, and was used in hospitals, clinics, insurance firms, hotels (as communication between the front desk and housekeeping), banks and train dispatching. Even the US Air Force used the Telautograph to disseminate weather reports. It’s true that the Telautograph is more akin to a fax machine than a contemporary tablet, yet it was the first electronic writing device to receive a patent, which was awarded in 1888.

Of course, ‘ol Elisha is better known for arriving at the US patent office on Valentine’s Day, 1876, with what he described as an apparatus “for transmitting vocal sounds telegraphically” just two hours after Mr. Alexander Graham Bell showed up with a description of a device that accomplished the same feat. After years of litigation, Bell was legally declared the inventor of what we now call the telephone, even though the device described in his original patent application wouldn’t have worked (Gray’s would have). So Gray/Bell have a Edison/Tesla thing going on.

Back to tablets.

Research Continues

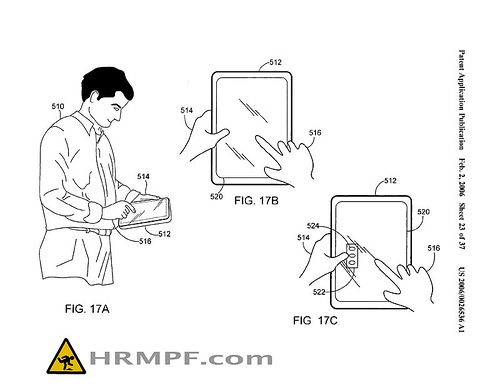

Research continued after the turn of the century. The US Patent Office awarded a patent to Mr. Hyman Eli Goldberg of Chicago in 1918, for his invention of the Controller. This device concerned the “a moveable element, a transmitting sheet, a character on said sheet formed of conductive ink and electrically controlled operating mechanism for said moveable element.” It’s considered the first patent awarded for a handwriting recognition user interface with a stylus.

Jumping ahead a bit, we find the Styalator (early 1950’s) and the RAND tablet (1964). Both used a pen and a tablet-like surface for input. The RAND (above) is more well-known and cost an incredible $18,000. Remember, that’s 18 grand in 1960?s money. Both bear little resemblance to contemporary tablet computers, and consisted of a tablet surface and an electronic pen. Their massive bulk — and price tags ?- made them a feasible purchase for few.

Alan Kay and the Dynabook

In 1968, things got real. Almost. Computer scientist Alan Kay 1 described his concept for a computer meant for children. His “Dynabook” would be small, thin, lightweight and shaped like a tablet.

In a paper entitled “A Personal Computer For Children Of All Ages,” [PDF] Kay described his vision for the Dynabook:

”The size should be no larger than a notebook; weigh less than 4 lbs.; the visual display should be able to present 4,000 printing quality characters with contrast ratios approaching that of a book; dynamic graphics of reasonable quality should be possible; there should be removable local file storage of at least one million characters (about 500 ordinary book pages) traded off against several hours audio (voice/music) files.”

In the video below, Kay explains his thoughts on the original prototype:

That’s truly amazing vision. Alas, the Dynabook as Kay envisioned it was never produced.

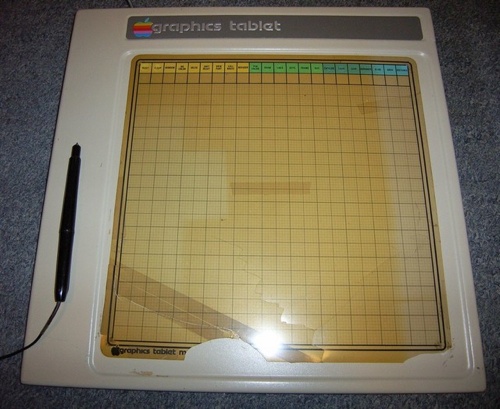

Apple’s First Tablet

The first commercial tablet product from Apple appeared in 1979. The Apple Graphics Tablet was meant to compliment the Apple II and use the “Utopia Graphics System” developed by musician Todd Rundgren. 2 That’s right, Todd Rundgren. The FCC soon found that it caused radio frequency interference, unfortunately, and forced Apple to discontinue production.

A revised version was released in the early 1980’s, which Apple described like this:

“The Apple Graphics Tablet turns your Apple II system into an artist’s canvas. The tablet offers an exciting medium with easy to use tools and techniques for creating and displaying pictured/pixelated information. When used with the Utopia Graphics Tablet System, the number of creative alternatives available to you multiplies before your eyes.

The Utopia Graphics Tablet System includes a wide array of brush types for producing original shapes and functions, and provides 94 color options that can generate 40 unique brush shades. The Utopia Graphics Tablet provides a very easy way to create intricate designs, brilliant colors, and animated graphics.”

The GRiDpad

This early touchscreen device cost $2,370 in 1989 and reportedly inspired Jeff Hawkins to create the first Palm Pilot. Samsung manufactured the GRiDpad PenMaster, which weighed under 5 lbs., was 11.5“ x 9.3” x 1.48? and ran on a 386SL 20MHz processor with a 80387SX coprocessor. It had 20 MB RAM and the internal hard drive was available at 40 MB, 60 MB, 80 MB or 120 MB. DigiBarn has a nice GRiDpad gallery.

The Newton Message Pad

With Steve Jobs out of the picture, Apple launched its second pen-computing product, the Newton Message Pad. Released in 1993, the Message Pad was saddled with iffy handwriting recognition and poor marketing efforts. Plus, the size was odd; too big to fit comfortably in a pocket yet small enough to suggest that’s where it ought to go.

The Newton platform evolved and improved in the following years, but was axed in 1998 (I still use one, but I’m a crazy nerd).

Knight-Ridder and the Tablet Newspaper

This one is compelling. Back in 1994, media and Internet publishing company Knight-Ridder 3 produced a video demonstrating its faith in digital newspaper. Its predictions are eerily accurate, except for this bold statement:

“Many of the technologists…assume that information is just a commodity and people really don’t care where that information comes from as long as it matches their set of personal interests. I disagree with that view. People recognize the newspapers they subscribe to…and there is a loyalty attached to those.”

Knight-Ridder got a lot right, but I’m afraid the technologists quoted above were wrong. Just ask any contemporary newspaper publisher.

The Late Pre-iPad Tablet Market

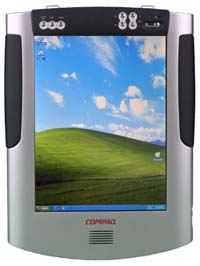

Many other devices appeared at this time, but what I call the “The Late Pre-iPad Tablet Market” kicked off when Bill Gates introduced the Compaq tablet PC in 2001. That year, Gates made a bold prediction at COMDEX:

“‘The PC took computing out of the back office and into everyone’s office,’ said Gates. ‘The Tablet takes cutting-edge PC technology and makes it available wherever you want it, which is why I’m already using a Tablet as my everyday computer. It’s a PC that is virtually without limits – and within five years I predict it will be the most popular form of PC sold in America.’”

Others followed, like the Axiotron ModBook, which is essentially an Apple MacBook modified into a tablet configuration (a “Pro” model has recently been released) and the Motion Computing LS800.

None of these devices, including those I didn’t mention, saw the success of the iPad. That must be due to in a large part to iOS. While the design was changing dramatically — flat, touch screen, light weight, portable — the operating system was stagnant and inappropriate. When Gates released the Compaq tablet in 2001, it was running Windows XP. That system was built for a desktop computer and it simply didn’t work on a touch-based tablet.

Meanwhile, others dreamed of what could be, unhindered by the limitations of hardware and software. Or reality.

Tablets in Pop Culture

The most famous fictional tablet device must be Star Trek’s Personal Access Display Device or “PADD.” The first PADDs appeared as large, wedge-shaped clipboards in the original Star Trek series and seemed to operate with a stylus exclusively. Kirk and other officers were always signing them with a stylus, as if the yeomen were interstellar UPS drivers and Kirk was receiving a lot of packages. 4

As new Trek shows were developed, new PADD models appeared. The devices went multi-touch in The Next Generation, adopting the LCARS Interface. A stylus was still used from time to time, though there was less signing. And signing. Aaand signing.

In Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, David Bowman and Frank Poole use flat, tablet-like devices to send and receive news from Earth. In his novel, Arthur C. Clarke described the “Newspad” like this:

“When he tired of official reports and memoranda and minutes, he would plug his foolscap-sized Newspad into the ship’s information circuit and scan the latest reports from Earth. One by one he would conjure up the world’s major electronic papers; he knew the codes of the more important ones by heart, and had no need to consult the list on the back of his pad. Switching to the display unit’s short-term memory, he would hold the front page while he quickly searched the headlines and noted the items that interested him.

Each had its own two-digit reference; when he punched that, the postage-stamp-sized rectangle would expand until it neatly filled the screen and he could read it with comfort. When he had finished, he would flash back to the complete page and select a new subject for detailed examination.

Floyd sometimes wondered if the Newspad, and the fantastic technology behind it, was the last word in man’s quest for perfect communications. Here he was, far out in space, speeding away from Earth at thousands of miles an hour, yet in a few milliseconds he could see the headlines of any newspaper he pleased. (That very word ‘newspaper,’ of course, was an anachronistic hangover into the age of electronics.) The text was updated automatically on every hour; even if one read only the English versions, one could spend an entire lifetime doing nothing but absorbing the ever-changing flow of information from the news satellites.

It was hard to imagine how the system could be improved or made more convenient. But sooner or later, Floyd guessed, it would pass away, to be replaced by something as unimaginable as the Newspad itself would have been to Caxton or Gutenberg.”

The iPad was released in 2010, so Clarke missed reality by only nine years. Not bad for a book published in 1968.

Next Time: Apple Rumors Begin

In the next article in this series, I’ll pick things up in the early 2000’s when rumors of an Apple-branded tablet gained momentum. For now, I’ll leave you with this quote from an adamant Steve Jobs, taken from an AllThingsD conference in 2003:

“Walt Mossberg: A lot of people think given the success you’ve had with portable devices, you should be making a tablet or a PDA.

Steve Jobs: There are no plans to make a tablet. It turns out people want keyboards. When Apple first started out, people couldn’t type. We realized: Death would eventually take care of this. We look at the tablet and we think it’s going to fail. Tablets appeal to rich guys with plenty of other PCs and devices already. I get a lot of pressure to do a PDA. What people really seem to want to do with these is get the data out. We believe cell phones are going to carry this information. We didn’t think we’d do well in the cell phone business. What we’ve done instead is we’ve written what we think is some of the best software in the world to start syncing information between devices. We believe that mode is what cell phones need to get to. We chose to do the iPod instead of a PDA.”

We’ll pick it up from there next time. Until then, go and grab your iPad and give a quiet thanks to Elisha Gray, Hyman Eli Goldberg, Alan Kay, the Newton team, Charles Landon Knight and Herman Ridder, Bill Gates and yes, Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and Gene Roddenberry. Without them and many others, you might not be holding that wonderful little device.

- More recently known as a co-developer on the the One Laptop Per Child machine. The computer itself was inspired, in part, by Kay’s work on the Dynabook.

- I’m really sorry for all the Flash on Todd’s site. It’s awful.

- Not Knight Rider.

- Not a euphemism. OK, maybe.