Thursday, January 17. 2013

Aleph of Emotions

Via prote.in

-----

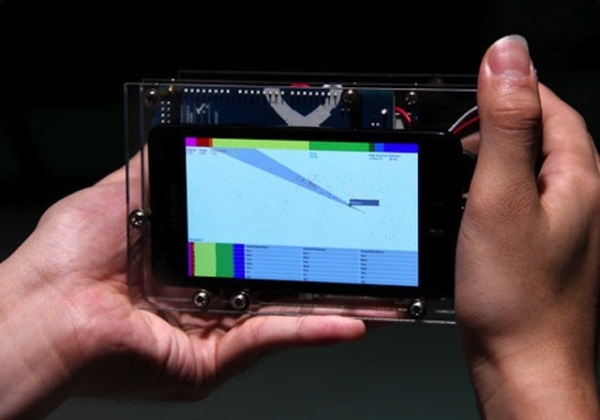

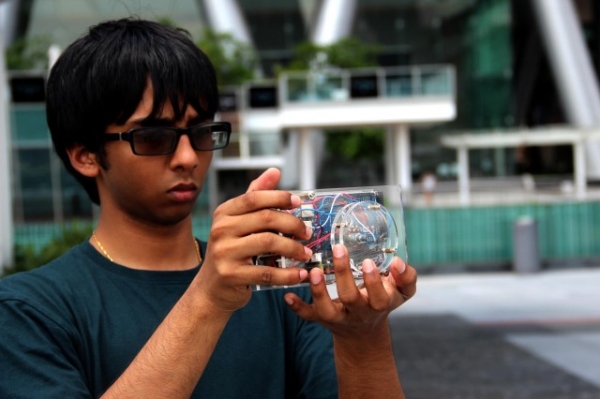

Bearing similarities to the Emoto project we looked at over the Summer, Mithru Vigneshwara's Aleph of Emotions uses location-based Twitter information to measure the 'mood' in various cities around the world.

Looking like a traditional camera, the user points the device in any direction and, combining the technology of a GPS, a smart phone and openFrameworks, the Aleph of Emotions captures and displays the emotional state people in major geographical locations.

This is another example of technology merging with intuitive design to measure or record concepts previously considered too abstract and intangible to be turned into meaningful data.

Tuesday, December 18. 2012

Depixelizing pixel art

-----

Naïve upsampling of pixel art images leads to unsatisfactory results.

Our algorithm extracts a smooth, resolution-independent vector

representation from the image which is suitable for high-resolution

display devices (Image © Nintendo Co., Ltd.).

Abstract

We describe a novel algorithm for extracting a resolution-independent vector representation from pixel art

images, which enables magnifying the results by an arbitrary amount

without image degradation. Our algorithm resolves pixel-scale features

in the input and converts them into regions with smoothly varying

shading that are crisply separated by piecewise-smooth contour curves.

In the original image, pixels are represented on a square pixel lattice,

where diagonal neighbors are only connected through a single point.

This causes thin features to become visually disconnected under

magnification by conventional means, and it causes connectedness and

separation of diagonal neighbors to be ambiguous. The key to our

algorithm is in resolving these ambiguities. This enables us to reshape

the pixel cells so that neighboring pixels belonging to the same feature

are connected through edges, thereby preserving the feature

connectivity under magnification. We reduce pixel aliasing artifacts and

improve smoothness by fitting spline curves to contours in the image

and optimizing their control points.

Paper

Paper

Full Resolution (4.16 MB)

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Click here

Wednesday, December 12. 2012

Why the world is arguing over who runs the internet

Via NewScientist

-----

The ethos of freedom from control that underpins the web is facing its first serious test, says Wendy M. Grossman

WHO runs the internet? For the past 30 years, pretty much no one. Some governments might call this a bug, but to the engineers who designed the protocols, standards, naming and numbering systems of the internet, it's a feature.

The goal was to build a network that could withstand damage and would enable the sharing of information. In that, they clearly succeeded - hence the oft-repeated line from John Gilmore, founder of digital rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation: "The internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around it." These pioneers also created a robust platform on which a guy in a dorm room could build a business that serves a billion people.

But perhaps not for much longer. This week, 2000 people have gathered for the World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT) in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates to discuss, in part, whether they should be in charge.

The stated goal of the Dubai meeting is to update the obscure International Telecommunications Regulations (ITRs), last revised in 1988. These relate to the way international telecom providers operate. In charge of this process is the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), an agency set up in 1865 with the advent of the telegraph. Its $200 million annual budget is mainly funded by membership fees from 193 countries and about 700 companies. Civil society groups are only represented if their governments choose to include them in their delegations. Some do, some don't. This is part of the controversy: the WCIT is effectively a closed shop.

Vinton Cerf, Google's chief internet evangelist and co-inventor of the TCP/IP internet protocols, wrote in May that decisions in Dubai "have the potential to put government handcuffs on the net".

The need to update the ITRs isn't surprising. Consider what has happened since 1988: the internet, Wi-Fi, broadband, successive generations of mobile telephony, international data centres, cloud computing. In 1988, there were a handful of telephone companies - now there are thousands of relevant providers.

Controversy surrounding the WCIT gathering has been building for months. In May, 30 digital and human rights organisations from all over the world wrote to the ITU with three demands: first, that it publicly release all preparatory documents and proposals; second, that it open the process to civil society; and third that it ask member states to solicit input from all interested groups at national level. In June, two academics at George Mason University in Virginia - Jerry Brito and Eli Dourado - set up the WCITLeaks site, soliciting copies of the WCIT documents and posting those they received. There were still gaps in late November when .nxt, a consultancy firm and ITU member, broke ranks and posted the lot on its own site.

The issue entered the mainstream when Greenpeace and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) launched the Stop the Net Grab campaign, demanding that the WCIT be opened up to outsiders. At the launch of the campaign on 12 November, Sharan Burrow, general secretary of the ITUC, pledged to fight for as long it took to ensure an open debate on whether regulation was necessary. "We will stay the distance," she said.

This marks the first time that such large, experienced, international campaigners, whose primary work has nothing to do with the internet, have sought to protect its freedoms. This shows how fundamental a technology the internet has become.

A week later, the European parliament passed a resolution stating that the ITU was "not the appropriate body to assert regulatory authority over either internet governance or internet traffic flows", opposing any efforts to extend the ITU's scope and insisting that its human rights principles took precedence. The US has always argued against regulation.

Efforts by ITU secretary general Hamadoun Touré to spread calm have largely failed. In October, he argued that extending the internet to the two-thirds of the world currently without access required the UN's leadership. Elsewhere, he has repeatedly claimed that the more radical proposals on the table in Dubai would not be passed because they would require consensus.

These proposals raise two key fears for digital rights campaigners. The first concerns censorship and surveillance: some nations, such as Russia, favour regulation as a way to control or monitor content transiting their networks.

The second is financial. Traditional international calls attract settlement fees, which are paid by the operator in the originating country to the operator in the terminating country for completing the call. On the internet, everyone simply pays for their part of the network, and ISPs do not charge to carry each other's traffic. These arrangements underpin network neutrality, the principle that all packets are delivered equally on a "best efforts" basis. Regulation to bring in settlement costs would end today's free-for-all, in which anyone may set up a site without permission. Small wonder that Google is one of the most vocal anti-WCIT campaigners.

How worried should we be? Well, the ITU cannot enforce its decisions, but, as was pointed out at the Stop the Net Grab launch, the system is so thoroughly interconnected that there is plenty of scope for damage if a few countries decide to adopt any new regulatory measures.

This is why so many people want to be represented in a dull, lengthy process run by an organisation that may be outdated to revise regulations that can be safely ignored. If you're not in the room you can't stop the bad stuff.

Wendy M. Grossman is a science writer and the author of net.wars (NYU Press)

Thursday, December 06. 2012

Temporary tatto as a medical sensor

Via FUTURITY

-----

A medical sensor that attaches to the skin like a temporary tattoo could make it easier for doctors to detect metabolic problems in patients and for coaches to fine-tune athletes’ training routines. And the entire sensor comes in a thin, flexible package shaped like a smiley face. (Credit: University of Toronto)

It looks like a smiley face tattoo, but a new easy-to-apply sensor can detect medical problems and help athletes fine-tune training routines.

“We wanted a design that could conceal the electrodes,” says Vinci Hung, a PhD candidate in physical and environmental sciences at the University of Toronto, who helped create the new sensor. “We also wanted to showcase the variety of designs that can be accomplished with this fabrication technique.”

The tattoo, which is an ion-selective electrode (ISE), is made using standard screen printing technique and commercially available transfer tattoo paper—the same kind of paper that usually carries tattoos of Spiderman or Disney princesses.

In the case of the sensor, the “eyes” function as the working and reference electrodes, and the “ears” are contacts for a measurement device to connect to.

Hung contributed to the work while in the lab of Joseph Wang, a professor at the University of California, San Diego. The sensor she helped make can detect changes in the skin’s pH levels in response to metabolic stress from exertion.

Similar devices are already used by medical researchers and athletic trainers. They can give clues to underlying metabolic diseases such as Addison’s disease, or simply signal whether an athlete is fatigued or dehydrated during training. The devices are also useful in the cosmetics industry for monitoring skin secretions.

But existing devices can be bulky or hard to keep adhered to sweating skin. The new tattoo-based sensor stayed in place during tests, and continued to work even when the people wearing them were exercising and sweating extensively.

The tattoos were applied in a similar way to regular transfer tattoos, right down to using a paper towel soaked in warm water to remove the base paper.

To make the sensors, Hung and colleagues used a standard screen printer to lay down consecutive layers of silver, carbon fiber-modified carbon and insulator inks, followed by electropolymerization of aniline to complete the sensing surface.

By using different sensing materials, the tattoos can also be modified to detect other components of sweat, such as sodium, potassium, or magnesium, all of which are of potential interest to researchers in medicine and cosmetology.

An article describing the work has been accepted for publication in the journal Analyst.

Tuesday, December 04. 2012

The Relevance of Algorithms

By Tarleton Gillespie

-----

I’m really excited to share my new essay, “The Relevance of Algorithms,” with those of you who are interested in such things. It’s been a treat to get to think through the issues surrounding algorithms and their place in public culture and knowledge, with some of the participants in Culture Digitally (here’s the full litany: Braun, Gillespie, Striphas, Thomas, the third CD podcast, and Anderson‘s post just last week), as well as with panelists and attendees at the recent 4S and AoIR conferences, with colleagues at Microsoft Research, and with all of you who are gravitating towards these issues in their scholarship right now.

The motivation of the essay was two-fold: first, in my research on online platforms and their efforts to manage what they deem to be “bad content,” I’m finding an emerging array of algorithmic techniques being deployed: for either locating and removing sex, violence, and other offenses, or (more troublingly) for quietly choreographing some users away from questionable materials while keeping it available for others. Second, I’ve been helping to shepherd along this anthology, and wanted my contribution to be in the spirit of the its aims: to take one step back from my research to articulate an emerging issue of concern or theoretical insight that (I hope) will be of value to my colleagues in communication, sociology, science & technology studies, and information science.

The anthology will ideally be out in Fall 2013. And we’re still finalizing the subtitle. So here’s the best citation I have.

Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Relevance of Algorithms. forthcoming, in Media Technologies, ed. Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo Boczkowski, and Kirsten Foot. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Below is the introduction, to give you a taste.

Algorithms play an increasingly important role in selecting what information is considered most relevant to us, a crucial feature of our participation in public life. Search engines help us navigate massive databases of information, or the entire web. Recommendation algorithms map our preferences against others, suggesting new or forgotten bits of culture for us to encounter. Algorithms manage our interactions on social networking sites, highlighting the news of one friend while excluding another’s. Algorithms designed to calculate what is “hot” or “trending” or “most discussed” skim the cream from the seemingly boundless chatter that’s on offer. Together, these algorithms not only help us find information, they provide a means to know what there is to know and how to know it, to participate in social and political discourse, and to familiarize ourselves with the publics in which we participate. They are now a key logic governing the flows of information on which we depend, with the “power to enable and assign meaningfulness, managing how information is perceived by users, the ‘distribution of the sensible.’” (Langlois 2012)

Algorithms need not be software: in the broadest sense, they are encoded procedures for transforming input data into a desired output, based on specified calculations. The procedures name both a problem and the steps by which it should be solved. Instructions for navigation may be considered an algorithm, or the mathematical formulas required to predict the movement of a celestial body across the sky. “Algorithms do things, and their syntax embodies a command structure to enable this to happen” (Goffey 2008, 17). We might think of computers, then, fundamentally as algorithm machines — designed to store and read data, apply mathematical procedures to it in a controlled fashion, and offer new information as the output.

But as we have embraced computational tools as our primary media of expression, and have made not just mathematics but all information digital, we are subjecting human discourse and knowledge to these procedural logics that undergird all computation. And there are specific implications when we use algorithms to select what is most relevant from a corpus of data composed of traces of our activities, preferences, and expressions.

These algorithms, which I’ll call public relevance algorithms, are — by the very same mathematical procedures — producing and certifying knowledge. The algorithmic assessment of information, then, represents a particular knowledge logic, one built on specific presumptions about what knowledge is and how one should identify its most relevant components. That we are now turning to algorithms to identify what we need to know is as momentous as having relied on credentialed experts, the scientific method, common sense, or the word of God.

What we need is an interrogation of algorithms as a key feature of our information ecosystem (Anderson 2011), and of the cultural forms emerging in their shadows (Striphas 2010), with a close attention to where and in what ways the introduction of algorithms into human knowledge practices may have political ramifications. This essay is a conceptual map to do just that. I will highlight six dimensions of public relevance algorithms that have political valence:

1. Patterns of inclusion: the choices behind what makes it into an index in the first place, what is excluded, and how data is made algorithm ready

2. Cycles of anticipation: the implications of algorithm providers’ attempts to thoroughly know and predict their users, and how the conclusions they draw can matter

3. The evaluation of relevance: the criteria by which algorithms determine what is relevant, how those criteria are obscured from us, and how they enact political choices about appropriate and legitimate knowledge

4. The promise of algorithmic objectivity: the way the technical character of the algorithm is positioned as an assurance of impartiality, and how that claim is maintained in the face of controversy

5. Entanglement with practice: how users reshape their practices to suit the algorithms they depend on, and how they can turn algorithms into terrains for political contest, sometimes even to interrogate the politics of the algorithm itself

6. The production of calculated publics: how the algorithmic presentation of publics back to themselves shape a public’s sense of itself, and who is best positioned to benefit from that knowledge.

Considering how fast these technologies and the uses to which they are put are changing, this list must be taken as provisional, not exhaustive. But as I see it, these are the most important lines of inquiry into understanding algorithms as emerging tools of public knowledge and discourse.

It would also be seductively easy to get this wrong. In attempting to say something of substance about the way algorithms are shifting our public discourse, we must firmly resist putting the technology in the explanatory driver’s seat. While recent sociological study of the Internet has labored to undo the simplistic technological determinism that plagued earlier work, that determinism remains an alluring analytical stance. A sociological analysis must not conceive of algorithms as abstract, technical achievements, but must unpack the warm human and institutional choices that lie behind these cold mechanisms. I suspect that a more fruitful approach will turn as much to the sociology of knowledge as to the sociology of technology — to see how these tools are called into being by, enlisted as part of, and negotiated around collective efforts to know and be known. This might help reveal that the seemingly solid algorithm is in fact a fragile accomplishment.

~ ~ ~

Here is the full article [PDF]. Please feel free to share it, or point people to this post.

Wednesday, November 28. 2012

NEC is working on a suitcase-sized DNA analyzer

Via PCWorld

-----

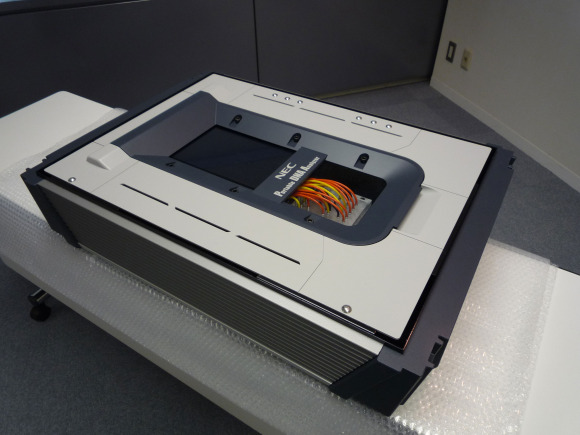

NEC is working on a suitcase-sized DNA analyzer, which it says will be able to process samples at the scene of a crime or disaster in as little as 25 minutes.

The company said it aims to launch the device globally in 2014, and sell it for around 10 million yen, or US$120,000. It will output samples that can be quickly matched via the growing number of DNA databases worldwide.

“At first we will target investigative organizations, like police,” said spokeswoman Marita Takahashi. “We will also push its use on victims of natural disasters, to quickly match samples from siblings and parents.”

NEC hopes to use research and software from its mature fingerprint and facial matching technology, which have been deployed in everyday devices such as smartphones and ATMs.

The company said that the need for cheaper and faster DNA testing became clear in the aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that devasted much of Japan’s northeast coastline last year, when authorities performed nearly 20,000 samples.

NEC pointed to growing databases such as CODIS (Combined DNA Index System) in the U.S. and a Japanese database of DNA samples.

The company said it is aiming to make the device usable for those with minimal training, requiring only a cotton swab or small blood sample. NEC aims to make a device that weighs around 35 kilograms, measuring 850 millimeters by 552mm by 240mm, about the size of a large suitcase. The unit will run on a 12V power source.

NEC said it will be able to complete three-stage analysis process using a “lab on a chip” process, a term for for technology that recreates lab processes on chip-sized components. The basic steps for analysis include extracting DNA from samples, amplifying the DNA for analysis, and then separating out the different DNA strands.

The current version of the analyzer takes about an hour for all three tasks, and NEC said it aims to lower that to 25 minutes.

NEC it is carrying out the development of the analyzer together with partners including Promega, a U.S. biotechnology firm, and is testing it with a police science research institute in Japan.

Tuesday, November 27. 2012

Smart light socket lets you control any ordinary light via Wi-Fi

Via DVICE

-----

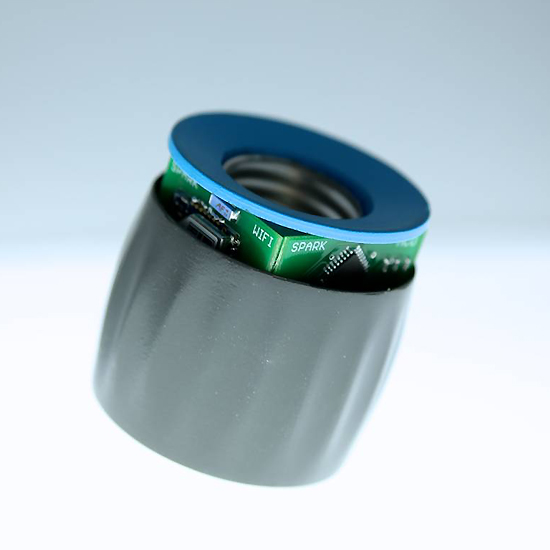

Internet-connected devices are clearly the future of controlling everything from your home to your car, but actually getting "the Internet of things" rolling has been slow going. Now a new project looks to brighten those prospects, quite literally, with a smart light socket.

Created by Zach Supalla (who was inspired by his father, who is deaf and uses lights for notifications), the Spark Socket lets you to connect the light sockets in your home to the Internet, allowing them to be controlled via PC, smartphone and tablet (iOS and Android are both supported) through a Wi-Fi connection. What makes this device so compelling is its simplicity. By simply screwing a normal light bulb into the Spark Socket, connected to a standard light fixture, you can quickly begin controlling and programming the lights in your home.

Some of the uses for the Spark Socket include allowing you to have your house lights flash when you receive a text or email, programming lights to turn on with certain alarms, and having lights dim during certain times of the day. A very cool demonstration of how the device works can be tested by simply visiting this live Ustream page and tweeting #hellospark. We tested it and the light flashed on instantly as soon as we tweeted the hashtag.

The device is currently on Kickstarter, inching closer toward its $250,000 goal, and if successful will retail for $60 per unit. You can watch Supalla offer a more detailed description of the product and how it came to be in the video below.

Friday, November 23. 2012

Why Big Data Falls Short of Its Political Promise

Via Mashable

-----

Politics Transformed: The High Tech Battle for Your Vote is an in-depth look at how digital media is affecting elections. Mashable explores the trends changing politics in 2012 and beyond in these special reports.

Big Data. The very syntax of it is so damn imposing. It promises such relentless accuracy. It inspires so much trust –- a cohering framework in a time of chaos.

Big Data is all the buzz in consumer marketing. And the pundits are jabbering about 2012 as the year of Big Data in politics, much as social media itself was the dizzying buzz in 2008. Four years ago, Obama stunned us with his use of the web to raise money, to organize, to get out the vote. Now it’s all about Big Data’s ability to laser in with drone-like precision on small niches and individual voters, picking them off one by one.

It in its simplest form, Big Data describes the confluence of two forces — one technological, one social. The new technological reality is the amount of processing power and analytics now available, either free or at no cost. Google has helped pioneer that; as Wired puts it, one of its tools, called Dremel, makes “big data small.”

This level of mega-crunchability is what’s required to process the amount of data now available online, especially via social networks like Facebook and Twitter. Every time we Like something, it’s recorded on some cosmic abacus in the sky.

Then there’s our browsing history, captured and made available to advertisers through behavioral targeting. Add to that available public records on millions of voters — political consultants and media strategists have the ability drill down as god-like dentists.

Website TechPresident describes the conventional wisdom of Big Data as it relates to elections:

… data is dominating both the study and practice of political campaigns. Most observers readily acknowledge that the 2012 presidential campaign will be decided by the outcome of a handful of battles in just a few key swing states — identified thanks to the reckoning of data scientists and pollsters.

There are two sides to the use of Big Data. One is predictive — Twitter has its own sentiment index, analyzing tweets as 140-character barometers. Other companies, like GlobalPoint, aggregate social data and draw algorithmic conclusions.

But Big Data has a role beyond digital clairvoyance. It’s the role of digital genotyping in the political realm. Simply find the undecided voters and then message accordingly, based on clever connections and peeled-back insights into voter belief systems and purchase behaviors. Find the linkages and exploit them. If a swing voter in Ohio watches 30 Rock and scrubs with Mrs. Meyers Geranium hand soap, you know what sites to find her on and what issues she cares about. Tell them that your candidate supports their views, or perhaps more likely, call out your opponent’s demon views on geranium subsidies.

Central to this belief is that the election won’t be determined by big themes but by small interventions. Big Data’s governing heuristic is that shards of insight about you and your social network will lead to a new era of micro-persuasion. But there are three fallacies that undermine this shiny promise.

Atomic Fallacy

The atomic fallacy is the assumption that just because you can find small, Seurat-like dots in my behavior which indicate preferences, you can motivate me by appealing to those interests.

Yes, I may have searched for a Prius out of curiosity. I may follow environmental groups or advocates on Twitter. I may even have Facebook friends who actively oppose off-shore drilling and fracking. Big Data can identify those patterns, but it still doesn’t mean that Romney’s support of the Keystone pipeline will determine my vote.

There are thousands of issues like this. We care about subjects and might research them online, and those subjects that might lead us to join certain groups, but they aren’t going to change our voting behavior. Candidates can go down a rabbit hole looking for them. Give a child a hammer and everything is a nail; give a data scientist a preference and everything is a trigger.

And then when a candidate gets it wrong — and that’s inevitable — all credibility is lost. This data delinquency was memorialized in a famous Wall Street Journal story a decade ago: “If TiVo Thinks You Are Gay, Here’s How to Set It Straight.”

Big Data still hasn’t solved its over-compensation problem when it comes to recommendations.

Interruption Fallacy

I define the interruption fallacy as the mistaken notion that a marketer or a candidate (the difference is only the level of sanctimony) can rudely insert his message and magically recalibrate deeply ingrained passions.

So even if Big Data succeeds in identifying subjects of paramount importance to me, the interruption fallacy makes it extremely unlikely that digital marketing can overcome what behavioral psychologists call the confirmation bias and move minds. Targeting voters can reinforce positions, but that’s not what pundits are concerned about. They’re opining that Big Data has the ability to shift undecideds a few points in the swing states.

Those who haven’t made up their minds after being assaulted by locally targeted advertising, with messaging that has been excruciatingly poll-tested, are victims of media scorch. They’re burned out. They are suffering from banner blindness. Big Data will simply become a Big Annoyance.

Mobile devices pose another set of challenges for advertisers and candidates, as Randall Stross recently pointed out in The New York Times. There’s a tricky and perhaps non-negotiable tradeoff between intrusiveness and awareness, as well as that pesky privacy issue. Stross writes:

Digital advertisers working with smartphones must somehow make their ads large enough to be noticed, but not so large as to be an interruption. And they must be chosen to match a user’s interests, but not so closely as to induce a shiver.

But that shiver is exactly what Big Data’s crunching is designed to produce– a jolt of hyper-awareness that can easily cross over into creepy.

And then there’s the ongoing decline in the overall effectiveness of online advertising. As Business Insider puts it, “The clickthrough rates of banner ads, email invites and many other marketing channels on the web have decayed every year since they were invented.”

No matter how much Big Data is being paid to slice and dice, we’re just not paying attention.

Narrative Fallacy

If Big Data got its way, elections would be decided based on a checklist that matched a candidate’s position with a voter’s belief systems. Tax the rich? Check. Get government off the back of small business? Check. Starve public radio? Check. It’s that simple.

Or is it? We know from neuromarketing and behavioral psychology that elections are more often than not determined by the way a candidate frames the issues, and the neural networks those narratives ignite. I’ve written previously for Mashable about The Political Brain, a book by Drew Westen that explains how we process stories and images and turn them into larger structures. Isolated, random messages — no matter how exquisitely relevant they are — don’t create a story. And without that psychological framework, a series of disconnected policy positions — no matter how hyper-relevant — are effectively individual ingredients lacking a recipe. They seem good on paper but lack combinatorial art.

This is not to say that Big Data has no role in politics. But it’s simply a part of a campaign’s strategy, not its seminal machinery. After all, segmentation has long enabled candidates to efficiently refine and target their messages, but the latest religion of reductionism takes the proposition too far.

And besides, there’s an amazing — if not embarrassing — number of Big Data revelations that are intuitively transparent and screechingly obvious. A Washington Post story explains what our browsing habits tell us about our political views. The article shared this shocking insight: “If you use Spotify to listen to music, Tumblr to consume content or Buzzfeed to keep up on the latest in social media, you are almost certainly a vote for President Obama.”

Similarly, a company called CivicScience, which offers “real-time intelligence” by gathering and organizing the world’s opinions, and that modestly describes itself as “a bunch of machines and algorithms built from brilliant engineers from Carnegie Mellon University,” recently published a list of “255 Ways to Tell an Obama Supporter from a Romney Supporter.” In case you didn’t know, Obama supporters favor George Clooney and Woody Allen, while mysteriously, Romney supporters prefer neither of those, but like Mel Gibson.

At the end of the day, Big Data can be enormously useful. But its flaw is that it is far more logical, predicable and rational than the people it measures.

Personal Comment:

Wednesday, November 21. 2012

Ban ‘Killer Robots’ Before It’s Too Late

-----

(Washington, DC) – Governments should pre-emptively ban fully autonomous weapons because of the danger they pose to civilians in armed conflict, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. These future weapons, sometimes called “killer robots,” would be able to choose and fire on targets without human intervention.

The 50-page report, “Losing Humanity: The Case Against Killer Robots,”

outlines concerns about these fully autonomous weapons, which would

inherently lack human qualities that provide legal and non-legal checks

on the killing of civilians. In addition, the obstacles to holding

anyone accountable for harm caused by the weapons would weaken the law’s

power to deter future violations.

“Giving machines the power to decide who lives and dies on the battlefield would take technology too far,” said Steve Goose,

Arms Division director at Human Rights Watch. “Human control of robotic

warfare is essential to minimizing civilian deaths and injuries.”

“Losing Humanity” is the first major publication about fully

autonomous weapons by a nongovernmental organization and is based on

extensive research into the law, technology, and ethics of these

proposed weapons. It is jointly published by Human Rights Watch and the

Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic.

Human Rights Watch and the International Human Rights Clinic called for

an international treaty that would absolutely prohibit the development,

production, and use of fully autonomous weapons. They also called on

individual nations to pass laws and adopt policies as important measures

to prevent development, production, and use of such weapons at the

domestic level.

Fully autonomous weapons do not yet exist, and major powers, including

the United States, have not made a decision to deploy them. But

high-tech militaries are developing or have already deployed precursors

that illustrate the push toward greater autonomy for machines on the

battlefield. The United States is a leader in this technological

development. Several other countries – including China, Germany, Israel,

South Korea, Russia, and the United Kingdom – have also been involved.

Many experts predict that full autonomy for weapons could be achieved in

20 to 30 years, and some think even sooner.

“It is essential to stop the development of killer robots before they

show up in national arsenals,” Goose said. “As countries become more

invested in this technology, it will become harder to persuade them to

give it up.”

Fully autonomous weapons could not meet the requirements of

international humanitarian law, Human Rights Watch and the Harvard

clinic said. They would be unable to distinguish adequately between

soldiers and civilians on the battlefield or apply the human judgment

necessary to evaluate the proportionality of an attack – whether

civilian harm outweighs military advantage.

These robots would also undermine non-legal checks on the killing of

civilians. Fully autonomous weapons could not show human compassion for

their victims, and autocrats could abuse them by directing them against

their own people. While replacing human troops with machines could save

military lives, it could also make going to war easier, which would

shift the burden of armed conflict onto civilians.

Finally, the use of fully autonomous weapons would create an

accountability gap. Trying to hold the commander, programmer, or

manufacturer legally responsible for a robot’s actions presents

significant challenges. The lack of accountability would undercut the

ability to deter violations of international law and to provide victims

meaningful retributive justice.

While most militaries maintain that for the immediate future humans

will retain some oversight over the actions of weaponized robots, the

effectiveness of that oversight is questionable, Human Rights Watch and

the Harvard clinic said. Moreover, military statements have left the

door open to full autonomy in the future.

“Action is needed now, before killer robots cross the line from science fiction to feasibility,” Goose said.

Thursday, November 15. 2012

Israel Announces Gaza Invasion Via Twitter, Marks The First Time A Military Campaign Goes Public Via Tweet

Via Fast Company

-----

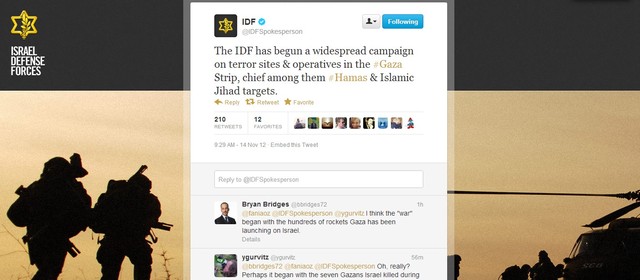

The Israeli military issued the world's first announcement of a military campaign via Twitter today with the disclosure of a large-scale, ongoing operation in Gaza. The Twitter announcement was made before a press conference was held.

A major Israeli military campaign in the Gaza Strip was announced today via Twitter in lieu of a formal press conference. The Israeli Defense Forces' official @IDFSpokesperson Twitter feed confirmed “a widespread campaign on terror sites & operatives in the #Gaza Strip,” called Operation Pillar of Defense, at approximately 9:30 a.m. Eastern time. Shortly before the tweet, Hamas' military head Ahmed al-Jabari was killed by an Israeli missile strike--Israel's military claims al-Jabari was responsible for numerous terror attacks against civilians. The IDF announcement on Twitter was the first confirmation made to the media of an official military campaign.

The Israeli military incursion follows months of rising tension in Gaza and southern Israel. More than 100 rockets have been fired at Israeli civilian targets since the beginning of November 2012, and Israeli troops have targeted Hamas and Islamic Jihad forces inside Gaza in attacks that reportedly included civilian casualties. According to the IDF spokespersons' office, the Israeli military is “ready to initiate a ground operation in Gaza” if necessary. Hamas' military wing, the Al-Qassam Brigades, operates the @alqassambrigade Twitter feed, which confirmed al-Jabari's death.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131055)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101667)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100067)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57896)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57463)

Categories

Show tagged entries

Syndicate This Blog

Calendar

|

|

February '26 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |