Monday, September 19. 2011

UNIVAC: the troubled life of America's first computer

Via ars technica

By Matthew Lasar

-----

It was November 4, 1952, and Americans huddled in their living rooms to follow the results of the Presidential race between General Dwight David Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson, Governor of Illinois. We like to think that our time is a unique moment of technological change. But the consumers observing this election represented an unprecedented generation of early adopters, who watched rather than listened to the race on the radio. By that year they had bought and installed in their homes about 21 million copies of a device called the television—about seven times the number that existed just three years earlier.

On that night they witnessed the birth of an even newer technology—a machine that could predict the election's results. Sitting next to the desk of CBS Anchor Walter Cronkite was a mockup of a huge gadget called a UNIVAC (UNIVersal Automatic Computer), which Cronkite explained would augur the contest. J. Presper Eckert, the UNIVAC's inventor, stood next to the device and explained its workings. The woman who actually programmed the mainframe, Navy mathematician Grace Murray Hopper was nowhere to be seen; for days her team had input voting statistics from earlier elections, then wrote the code that would allow the calculator to extrapolate the contest based on previous races.

J. Presper Eckert and CBS's Walter Cronkite pondering the UNIVAC on election night, 1952.

To the disquietude of national pollsters expecting a Stevenson victory, Hopper's UNIVAC group predicted a huge landslide for Eisenhower, and with only five percent of the results. CBS executives didn't know what to make of this bold finding. "We saw [UNIVAC] as an added feature to our coverage that could be very interesting in the future," Cronkite later recalled. "But I don't think that we felt the computer would become predominant in our coverage in any way."

And so CBS told its audience that UNIVAC only foresaw a close race. At the end of the evening, when it was clear that UNIVAC's actual findings were spot on, a spokesperson for the company that made the machine was allowed to disclose the truth—that the real prediction had been squelched.

"The uncanny accuracy of UNIVAC's prediction during a major televised event sent shock waves across through the nation," notes historian Kurt W. Beyer, author of Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age. "In the months that followed, 'UNIVAC' gradually became the generic term for a computer."

That's putting it mildly. By the late 1950s the UNIVAC and its cousin, the ENIAC, had inspired a generic sobriquet for anyone with computational prowess—a "BRAINIAC." The term became so embedded in American culture that to this day your typical computer literacy quiz includes the following multiple choice poser:

Which was not an early mainframe computer?

- ENIAC

- UNIVAC

- BRAINIAC

But the fact that this question is even posed is testimony to the other key component of UNIVAC's history—its famous trajectory was cut short by a corporation with a much larger shadow: IBM. The turbulent life of UNIVAC offers interesting lessons for developers and entrepreneurs in our time.

The machines and their teams

During the Second World War, two teams in the United States were deployed to improve the calculations necessary for artillery firing and strategic bombing. Hopper worked with Harvard mathematician Howard Aiken, whose Mark I computer performed computations for the Navy. John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert's Electronic and Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) rolled out rocket firing tables for the Army.

While both groups served extraordinarily during the war, their leaders could not have thought about these devices more differently. Aiken viewed them as scientific tools. Mauchly saw their potential as commercial instruments.

After the conflict, Aiken obstinately lobbied against the commercialization of computing, inveighing against the "foolishness with Eckert and Mauchly," at computer conferences. Perhaps there was a need for five or six machines in the country, he told associates; no more. But Aiken's assistant Hopper was fascinated by the duo—the former a graduate student and the latter a professor of electronics.

Eckert was "looking way ahead," Hopper recalled. "Even though he was a college professor he was visualizing the use of these computers in the business and industrial area." The University of Pennsylvania sided with Aiken. The college offered Eckert and Mauchly tenured positions, but only on the condition that they sign patent releases for all their work. Both inventors resigned from the campus and in the spring of 1946 formed the Electronic Control Company, which eventually became the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation.

Over the course of five years, the two developers rethought everything associated with computational machines. The result was a device that went way beyond the age of punch card calculators associated with IBM devices. The UNIVAC, unveiled in 1951, was the fruit of this effort.

"No one who saw a UNIVAC failed to see how much it differed from existing calculators and punched card equipment," writes historian Paul E. Ceruzzi:

It used vacuum tubes—thousands of them. It stored data on tape, not cards. It was a large and expensive system, not a collection of different devices. The biggest difference was its internal design, not visible to the casual observer. The UNIVAC was a "stored program" computer, one of the first. More than anything else, that made it different from the machines it was designed to replace.

These characteristics would enable the UNIVAC to perform thousands more operations per second than its closest rival, the Harvard Mark II. And its adaptation of the entertainment industry's new tool—magnetic recording tape—would allow it to store vastly more data. UNIVAC was quickly picked up by the US Census Bureau in a $300,000 contract, which was followed by another deal via the National Bureau of Standards. Soon a racetrack betting odds calculator company called American Totalisator signed on, purchasing a 40 percent interest in the company.

You could see and hold it

But Eckert-Mauchly could not handle this volume of work on its own. Its principals drastically underbid on key contracts. After a plane crash killed the corporation's board president, the inventors and Totalisor clashed over the viability of the project. The duo then went to IBM for backing and met with Thomas Watson Junior and Senior, but could not convince the elder executive of the UNIVAC's viability.

"Having built his career on punch cards," Watson Jr. later reflected, "Dad distrusted magnetic tape instinctively. On a punch card, you had a piece of information that was permanent. You could see it and hold it in your hand.... But with magnetic tape, your data were stored invisibly on a medium that was designed to be erased and reused."

So EMCC turned to its second choice—the Remington Rand office equipment company, whose founder James Rand expressed outrage when he saw a reworked IBM typewriter rather than a Remington hooked up to the UNIVAC. "Take that label off that machine!" Rand declared on his first visit to an EMCC laboratory. "I don't want it seen in here!"

The tenderness over an IBM logo aside, Remington Rand brought an important innovation to the UNIVAC—television advertisements. The longer infomercials came complete with symphony orchestra introductions and historical progress timelines that began with the Egyptian Sphinx. The shorter ones extolled the role that UNIVAC was playing in weather prediction. "Today UNIVAC is saving time and increasing efficiency for science, industry, business, and government," one ad concluded.

A Remington Rand UNIVAC commercial.

But while that was certainly true about what the machine did for its clients, historian Beyer notes that it didn't extend to Remington's management of EMCC. Most of the office company's top staff, like its founder, didn't understand the device, and related more to punch card machines. The man put in direct charge of EMCC, former Manhattan Project director Leslie Groves, tossed Mauchly to the sales department when he flunked a company security clearance test (apparently he had attended some Communist Party meetings in the 1930s).

On top of that, new management did not sympathize with EMCC's female programmers, among them Grace Hopper, who by 1952 had written the UNIVAC's first software compiler. "There were not the same opportunities for women in larger corporations like Remington Rand," she later reflected. "They were older companies, and the jobs had been stereotyped."

Then there was Groves' marketing strategy for the UNIVAC, which amounted to selling less of the devices, even as they were being hawked on TV as exemplars of technological progress. He ordered a fifty percent annual production quota drop. "With such low sales expectations, there was little incentive to educate Remington Rand's sizeable sales force about the new technology," Beyer explains.

The biggest blow, however, came when IBM began to rethink its aversion to magnetic mainframe storage.

Left in the dust

Despite Remington/EMCC's internal chaos, interest in the UNIVAC exploded after the 1952 CBS demonstration. This created more problems. Hopper's programming staff was now besieged with attractive offers from companies using IBM gear, creating a brainiac drain within EMCC itself. "Some members of Dr. Grace Hopper's staff have already left for positions with users of IBM equipment," Mauchly noted in a memo, "and those of her staff who still remain are now expecting attractive offers from outside sources."

Customer service and support became more and more of a challenge. Still, the UNIVAC was highly competitive with IBM equipment. The question was whether EMCC could beat Big Blue in government contract bidding, specifically for the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) defense communications network.

The SAGE project amounted to an early-warning radar system designed to pick up enemy bomber activity around the nation's borders. It was the brainchild of Jay Forrester, director of MIT's Sernomechanisms Laboratory, and central to the idea was a network of digital computers to integrate the network, dubbed "Project Whirlwind." In three years Forrester's team had pioneered real-time, high-capacity access memory for the mainframes. The government now offered a contract to build 50 Whirlwind computers. IBM quickly rallied its forces for the contest.

"I thought it was absolutely essential to IBM's future that we win it," Thomas Watson Jr., who had none of Senior's allergies to digital computing, later explained. "The company that built those computers was going to be way ahead of the game, because it would learn the secrets of mass production."

Forrester gave the matter some thought. Remington Rand had UNIVAC. And it had the prestige of Manhattan Project Director Leslie Groves. But Remington did not have IBM's scale of operation or its production capacity. Indeed, under Groves' direction, it had scaled that capacity down. In 1953, the government offered the contract to IBM. Historian Beyer explains the consequences of this decision:

Not only did IBM take away knowledge about random-access magnetic core memory; they also learned how the Whirlwind team had pushed the technological envelope in a number of other areas. Forrester's staff had figured out a variety of ways to lower the frequency of vacuum-tube failure, thus increasing system reliability. Cathode-ray-tube displays were ingeniously employed to display processed information, index registers made programming easier, and real-time information from radar sensors could be processed without the need for a slow input medium such as punch cards.

IBM quickly integrated these discoveries into its next rollout of commercial computers. The market loved them and ordered thousands. "In a little over a year we started delivering those redesigned computers," Watson Jr. later boasted. "They made the UNIVAC obsolete and we soon left Remington Rand in the dust."

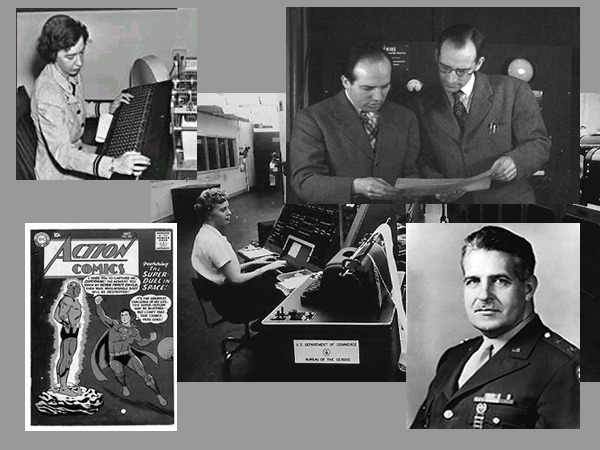

The UNIVAC universe of the 1950s—clockwise from top left: UNIVAC mathematician and programmer Grace Hopper; John W. Mauchly and John Presper Eckert; General Leslie Groves of Remington Rand; DC Comics' Brainiac confronting Superman in 1959; a Department of Commerce UNIVAC in the center.

Aftermath

Sensing the dust around it, in 1955 Remington merged with the Sperry Corporation and became Sperry Rand. No less than General Douglas MacArthur ran the new entity. This gave the UNIVAC a new lease on digital life, but one that operated in the shadow of the company that had once sworn that it would stick to punch tape: IBM.

In the meantime, a slew of firms jumped into the high-speed computing business, among them RCA, National Cash Register, General Electric, and Honeywell. "IBM and the Seven Dwarfs," they were dubbed. UNIVAC was now a dwarf.

Grace Hopper continued her work. She became an advocate of the assumption inherent in her UNIVAC compiler which she called "automatic" computing—the notion that programs should emphasize simple English words. Her compiler, later called FLOW-MATIC, understood 20 words.

Her contemporaries patiently informed her that this number was enough. Hopper "was told very quickly that [she] couldn't do this because computers didn't understand English," she later noted. Happily, she did not believe this to be true, and advised a team that developed the COBOL programming language, which she championed and furthered through the 1960s and 1970s. US Navy Rear-Admiral Grace Murray Hopper died in 1992.

Having fattened IBM on government grants for decades, the Department of Justice launched an antitrust suit against the corporation in 1969. This initiative was suddenly withdrawn by the Reagan administration in 1982—as the company once again jolted the industry by jumping into the PC market.

As for UNIVAC, its complex birth 60 years ago remains the moment when we discovered that computers were going to be part of our lives—that they were going to become integral our work and collective imagination. It was also a moment when information systems developers and entrepreneurs learned that innovation and genius are not always a match for influence and organizational scale.

"Howard Aiken was wrong," historian Paul Cerruzi wrote in 2000. "There turned out to be a market for millions of electronic digital computers by the 1990s." Their emergence awaited advances in solid state physics. Nonetheless, "the nearly ubiquitous computers of the 1990s are direct descendants of what Eckert and Mauchly hoped to commercialize in the late 1940s."

Further reading

Most of the material in this essay comes from Kurt W. Beyer's must-read book, Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age (MIT Press). Also essential is Paul E. Ceruzzi's History of Modern Computing.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131079)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101711)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100096)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57940)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57520)