Friday, April 27. 2012

Via ifixit.org

-----

The iPad’s light, sleek, simple construction belies its complex

origins. There’s a lot of stuff in the iPad: aluminum and glass, of

course, but also other heavy metals and toxic chemicals. And

manufacturing each 1.44-pound iPad results in over 285 times

its own weight in greenhouse gas emissions. The manufacturing of and

material used in the iPad are two reasons why the iPad must be made in

China—and not just in the ways you’d expect.

Yes, labor is dirt cheap in China. Minimum wage was just $138/month at Hongkai Electronics in October 2010, compared to $1160/month in the US (based on a $7.25/hour federal minimum wage and a 40-hour work week).

And yes, environmental regulations in China are pretty minimal (though improving). China ranks 116th out of 132 countries on Yale’s 2012 Environmental Performance Index

rankings. Even with all their illegally run coltan mines, the

Democratic Republic of Congo is ranked many points higher than China.

But there’s another important reason why Apple and other

manufacturers have their heels stuck in Chinese mud. iPad manufacturing,

like the manufacturing of other electronics, requires a significant

amount of rare earth elements, the 17 difficult-to-mine elements used in

all kinds of green technology. It’s hard to say exactly what rare

earths are in an iPad, since Apple is really tight-lipped about their

materials—no one can even get them to confirm what manufacturer makes

their impact-resistant glass, though I suspect Asahi.

Cambridge engineering professor Dr. Tim Coombs

guesses that there may be lanthanum in the iPad’s lithium-ion polymer

battery, as well as “a range of rare earths to produce the different

colours” in the display. The magnets along the side of the iPad and in its cover (pictured above) are possibly a neodymium alloy. Electronics glass is often polished with cerium oxide. According to a Congressional Research Service report, worldwide demand for rare earths was 136,100 tons in 2010, 45-percent of which was for magnets, glass, and polishing.

All Our Rare Earths Come from a Pit Mine in China

Why is all this rare earth consumption a problem? China currently controls 95-97%

of the world’s supply of rare earths and has repeatedly cut export

quotas, sending already-high prices skyrocketing. Fearing dependence on

China for rare earths, two companies—Molycorp in California and Lynas Corp in Australia—plan

to begin mining rare earths this year. As green industry continues to

grow, however, it’s unclear if current mining operations will be able to

keep up with increasing demand.

Facing growing concern about the possibility of a rare earth shortage, President Obama recently lodged a complaint with the World Trade Organization against China about their rare earth policy. Some specialists think the complaint may be “too little, too late”—by the time China changes its policy, more manufacturers will have moved plants to China.

Recycling is Not a Rare Earth Solution

It might seem that the mountains of electronic waste would be a

perfect source of rare earths. But recycling isn’t the answer to the

rare earth shortage—at least not yet. Some Japanese recyclers are successfully recovering rare earths from compressors. But neither SIMS Recycling Solutions nor Electronics Recyclers International (ERI),

the two biggest electronics recyclers in the US, are currently

recovering any rare earths in their recycling process, according to SIMS

president Steve Skurnac and ERI CEO John Shegerian.

For now, Skurnac says, “Rare earths come in very minute

concentrations in electronic scrap,” which means that recyclers need

high volume and super efficient processes to recover any reasonable

amount of rare earths from electronics. The technology just isn’t there

to make it economically feasible for most recyclers.

Today, an American electronics company can only be exempt from

China’s rare earth export quotas by manufacturing within China. So

that’s what most companies, including Apple, are doing. The only other

solution is for us to stop consuming so much—an option that people

rarely find appealing. Not as appealing as a retina display, at least.

Wednesday, April 11. 2012

Via hack education

-----

"25 million laptops later," Mashable announced today, "One Laptop Per Child doesn't increase test scores." "Error Message," reads the headline from The Economist: "A disappointing return from an investment in computing."

The tenor of these stories feels like a grand "Gotcha!"

for ed-tech: It's shiny stuff, sure, but it offers no measurable gains

in "student achievement." So while the OLPC project might have been a

good idea, so the story goes, it is not a good investment.

One Laptop Per Child was a good idea, a noble and ambitious

one at that. Originally proposed in 2006, OLPC aimed to build an

inexpensive laptop that would be sold to governments in the developing

world and made available in turn to the children in those countries via

their respective ministries of education. Easier said than done. Over

the course of the past 6 years, the OLPC has fussed with hardware and

software specs, finally building a laptop (and now, a tablet) that costs $200 (twice that of the originally promised price).

In the meantime, much of the developing world has experienced its own

mobile computing revolution. There are now a number of manufacturers

working on low-cost devices for that market. There's the Intel Classmates PC, for example (with similar hardware, but more expensive software than its OLPC coursin); there's the Worldreader project (it delivers villages a library full of e-books via Kindles); and there's the now-infamous Aakash tablet (which was sold in India for $35 but with its reliability and functionality very much in question).

Arguably more significant than the competition OLPC faces from these low-cost tablets and netbooks: 95% of the world's population now owns a cellphone, by some estimates (See Wikipedia's list

of mobile phone penetration, broken down by country). Of course, a

clamshell phone is hardly the same as a laptop. One has SMS; the other, a

command line. Nonetheless, the ubiquity of the cellphone makes it

clear that the value proposition of the OLPC device needs to be more

than just "access" and "connectivity."

The mission of the non-profit organization always stressed something

broader, bigger -- One Laptop per Child meant empowerment, engagement,

and education:

We aim to provide each child with a rugged, low-cost,

low-power, connected laptop. To this end, we have designed hardware,

content and software for collaborative, joyful, and self-empowered

learning. With access to this type of tool, children are engaged in

their own education, and learn, share, and create together. They become

connected to each other, to the world and to a brighter future.

No mention of improving standardized test scores in there, you'll

notice. No talk of "student achievement." "The best preparation for

children," according to the OLPC website isn't test prep. It is "to develop the passion for learning and the ability to learn how to learn."

Standardized test scores in math and in language do not reflect "the

ability to learn how to learn" -- they don't even purport to. But we

fixate on test scores nevertheless. It is worth noting here that the

study that prompted today's headlines about OLPC's "disappointing" test

results -- one conducted by the Inter-American Development Bank

using data collected from some 300 primary schools in rural Peru -- did

find some improvement in students' cognitive skills (as in, "the

ability to learn how to learn").

The study links that boost in cognitive skills to "increased

interaction with technology." Make of that what you will. The study

also found that having access to computers increases your access to

computers. To quote Keanu Reeves here, "Whoa."

The study points out other things too, and it asks "Could stricter

adherence to the OLPC principles have brought about better academic

outcomes?" Many students were not allowed to take their laptops home.

Internet access was "practically non-existent." Just 70% of teachers

had 40-hours of professional development before their students were

given the devices.

That last (missing) piece -- training for teachers -- has long been

something that gets overlooked when it comes to ed-tech initiatives no

matter the location, Peru or the U.S. It is almost as if we believe we

can simply parachute technology in to a classroom and expect everyone to

just pick it up, understand it, use it, hack it, and prosper.

Oh right. OLPC has done just that, a la The Gods Must Be Crazy,

whereby tablets were quite literally dropped into villages from

helicopters. Okay, not everyone receives their devices this way, but

OLPC has always been fairly hands-off in its training implementation

efforts. It's one of the major criticisms that the organization has

faced (along with criticisms about price, hardware, software, and

environmental sustainability).

For his part, Nicholas Negroponte, the head of the OLPC foundation,

frequently points to the work of Sugata Mitra and the "Hole in the Wall

Project" as inspiration

-- the belief that children can learn (and teach each other) on their

own. Children are naturally inquisitive; they are ingenious. Access to

an Internet-enabled computing device is sufficient. They will "figure

it out."

It's part of what Mitra and Negroponte call a "minimally invasive education."

Considering the colonial legacy of education systems in the developing

world, avoiding "invasion" seems profoundly important.

But there remains a strange tension between dropping in a Western

technological "solution" and insisting doing so is "non-invasive." At

it's best, the OLPC represents a desire to support literacy,

connectivity and learning through technology. But it does those things

in a world of ubiquitous cellphones, which on their own have not

transformed education either. In an effort to be "non-invasive" then,

OLPC ends up often being unsupportive -- unsupportive of the tech, the

teachers and the learners.

But is that failure? It doesn't feel like pointing to standardized

test scores in math and language is the right measure at all to gauge

this. It goes against the core of the OLPC mission. But then again,

these measurements are political, not necessarily pedagogical. And

these scores reveal less about the global reach or potential of

technology, and more about the dominant narratives of the U.S. education

system: "what counts" as learning, and "what counts" in terms of

ed-tech's role in delivering or enabling it -- why, standardized test

scores, of course.

Photo credits: OLPC

Friday, April 06. 2012

Via Vanity Fair

---

When the Internet was created, decades ago, one thing was inevitable:

the war today over how (or whether) to control it, and who should have

that power. Battle lines have been drawn between repressive regimes and

Western democracies, corporations and customers, hackers and law

enforcement. Looking toward a year-end negotiation in Dubai, where 193

nations will gather to revise a U.N. treaty concerning the Internet,

Michael Joseph Gross lays out the stakes in a conflict that could split

the virtual world as we know it.

Access to the full article @Vanity Fair

Thursday, April 05. 2012

Via Wired

-----

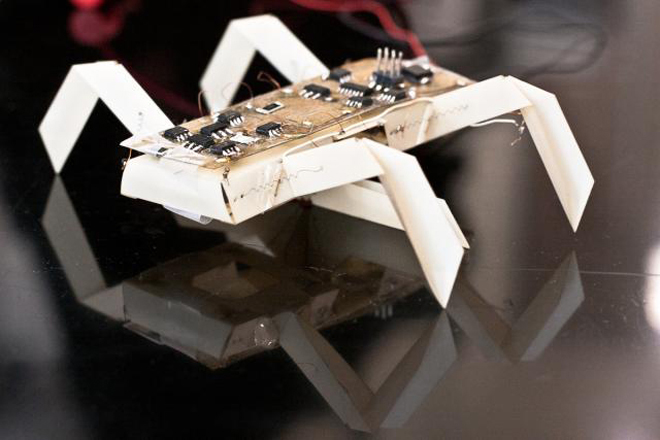

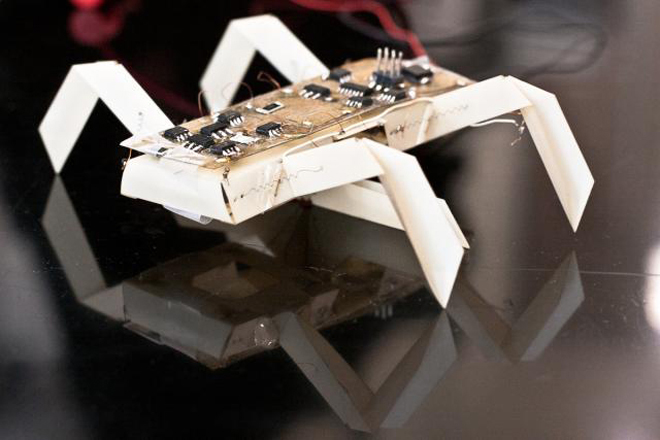

Insect printable robot. Photo: Jason Dorfman, CSAIL/MIT

Printers can make mugs, chocolate and even blood vessels. Now, MIT scientists want to add robo-assistants to the list of printable goodies.

Today, MIT announced a new project, “An Expedition in Computing

Printable Programmable Machines,” that aims to give everyone a chance to

have his or her own robot.

Need help peering into that unreasonably hard-to-reach cabinet, or

wiping down your grimy 15th-story windows? Walk on over to robo-Kinko’s

to print, and within 24 hours you could have a fully programmed working origami bot doing your dirty work.

“No system exists today that will take, as specification, your

functional needs and will produce a machine capable of fulfilling that

need,” MIT robotics engineer and project manager Daniela Rus said.

Unfortunately, the very earliest you’d be able to get your hands on

an almost-instant robot might be 2017. The MIT scientists, along with

collaborators at Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania,

received a $10 million grant from the National Science Foundation for

the 5-year project. Right now, it’s at very early stages of development.

So far, the team has prototyped two mechanical helpers: an

insect-like robot and a gripper. The 6-legged tick-like printable robot

could be used to check your basement for gas leaks or to play with your

cat, Rus says. And the gripper claw, which picks up objects, might be

helpful in manufacturing, or for people with disabilities, she says.

Printable gripper. Photo: Jason Dorfman, CSAIL/MIT

The two prototypes cost about $100 and took about 70 minutes to

build. The real cost to customers will depend on the robot’s

specifications, its capabilities and the types of parts that are

required for it to work.

The researchers want to create a one-size-fits-most platform to

circumvent the high costs and special hardware and software often

associated with robots. If their project works out, you could go to a

local robo-printer, pick a design from a catalog and customize a robot

according to your needs. Perhaps down the line you could even order-in

your designer bot through an app.

Their approach to machine building could “democratize access to

robots,” Rus said. She envisions producing devices that could detect

toxic chemicals, aid science education in schools, and help around the

house.

Although bringing robots to the masses sounds like a great idea (a

sniffing bot to find lost socks would come in handy), there are still

several potential roadblocks to consider — for example, how users,

especially novice ones, will interact with the printable robots.

“Maybe this novice user will issue a command that will break the

device, and we would like to develop programming environments that have

the capability of catching these bad commands,” Rus said.

As it stands now, a robot would come pre-programmed to perform a set

of tasks, but if a user wanted more advanced actions, he or she could

build up those actions using the bot’s basic capabilities. That advanced

set of commands could be programmed in a computer and beamed wirelessly

to the robot. And as voice parsing systems get better, Rus thinks you

might be able to simply tell your robot to do your bidding.

Durability is another issue. Would these robots be single-use only?

If so, trekking to robo-Kinko’s every time you needed a bot to look

behind the fridge might get old. These are all considerations the

scientists will be grappling with in the lab. They’ll have at least five

years to tease out some solutions.

In the meantime, it’s worth noting that other other groups are also building robots using printers. German engineers printed a white robotic spider last year. The arachnoid carried a camera and equipment to assess chemical spills.

And at Drexel University, paleontologist Kenneth Lacovara and mechanical engineer James Tangorra are trying to create a robotic dinosaur from dino-bone replicas.

The 3-D-printed bones are scaled versions of laser-scanned fossils. By

the end of 2012, Lacovara and Tangorra hope to have a fully mobile

robotic dinosaur, which they want to use to study how dinosaurs, like

large sauropods, moved.

Lancovara thinks the MIT project is an exciting and promising one:

“If it’s a plug-and-play system, then it’s feasible,” he said. But

“obviously, it [also] depends on the complexity of the robot.” He’s seen

complex machines with working gears printed in one piece, he says.

Right now, the MIT researchers are developing an API that would

facilitate custom robot design and writing algorithms for the assembly

process and operations.

If their project works out, we could all have a bot to call our own in a few years. Who said print was dead?

Wednesday, April 04. 2012

Via Christian Babski

-----

8 bits edition of Google maps. We are all stars now in the game show.

Monday, April 02. 2012

Via The Atlantic Wire

-----

flickr/Jeff Dlouhy

While Apple and Google are busy getting bad press for their privacy

issues, labor practices and general big-evil-company wrongdoings,

Microsoft has done some brand regeneration, making it look like the

hippest tech company on the block these days. As Apple and Google

captured a younger, cooler demographic, the Windows maker, with its

stodgy business oriented PC-compatible operating system and notoriously

annoying browser, became synonymous with lameness. Remember all those

highly effective Mac versus PC commercials?

That PC dork (writer-performer John Hodgman) represented all things

Microsoft: Slow, uptight, badly dressed. But as Apple and Google have

grown up, they've lost their hip sheen. And, Microsoft's taking

advantage. In this era of awesomely bad, it doesn't look so lame anymore

-- especially in comparison to the other guys.

We noticed this new-found hipness when we came across the endearing Browser You Love(d) to Hate

campaign. With some admirable self-awareness, Microsoft used its own

bad reputation to argue that its hated Internet Explorer browser is on

the verge of a comeback. Layering on the hipster-irony, Microsoft

compares itself to once-passe things like PBR and mustaches, suggesting

it's just another brand that's so bad, it's cool again. It also doesn't

hurt that the overall look of the site matches that aesthetic. The Atlantic's own mustachio-ed tech man, Alexis Madrigal gave it his approval, calling this accompanying ad "definitely the funniest commercial Microsoft's ever put out." We agreed, finding the whole thing convincing enough to give our abandoned IE9 a try again. (We still prefer Chrome, by the way.)

But this image comeback isn't limited to IE. Over the last few days we've seen Hotmail ads running on Boing Boing and Jezebel,

two blogs that are hip for different reasons. Boing Boing catering to

the hippest of Internet lovers and Jezebel reaches a more mainstream but

still cool millennial audience. And in general, the overall

Microsoft-related press has been kind of good. Windows 8 surprised and excited

the tech blogger world, something a Windows browser hasn't done since

Windows 95. The company has some other exciting things going on inside

its labs. The other day, It did some Internet good with its Digital Crimes Unit. And, has even designed itself a decent looking logo. Apple's (maybe) new logo, on the other hand, with its rainbow mish-mash, feels dated.

Which brings us to the other aspect of Microsoft's renaissance: good

timing. The once-hipper than Microsoft foes, Google and Apple haven't

looked so good these days. Google, the once beloved search company, has

users uneasy with its Google+ integration, privacy issues and anti-trust concerns. Even Googlers aren't too sure

of Google's mission, these days. Appl still produces insane-popular

gadgets, but no longer wows reviewers like it once did. The new iPad is

still the best tablet out there, but it's not a must-have. Plus, it too

has gotten itself into its own privacy messes. It also had the misfortune of acting as the face of the last few months of Foxconn scandal.

Though the Foxconn protesters that threatened mass suicide back in

January made Microsoft's XBox, thanks to Mike Daisey and Apple's

financial successes, Apple not Microsoft absorbed most of the bad PR.

Part of this has to do with maturity, we suppose. An early bloomer,

Microsoft's already went through its tech company growing pains. It used

to be the evil one, remember? The one accused of monopolistic practices, of buying up the competition, of stifling innovation. But

it's no longer the bully. Google and Apple's misdeeds have

overshadowed the once dominant tech company, and while the other big

players make public messes out of themselves, Microsoft looks to be

cleaning up its image. And, we have to say, it looks good.

|