Entries tagged as privacy

Related tags

artificial intelligence algorythm automation big data car cloud computing data visualisation google hardware innovation&society neural network program programming sensors software super computer technology cloud data mining browser chrome firefox history ie network web amazon apple computing farm microsoft open source piracy security sustainability ai art crowd-sourcing flickr gui internet internet of things maps mobile photos DNA genome surveillance usb facial recognition API tracking dna android api book chrome os display glass interface laptop mirror hack 3d 3d printing 3d scanner ad amd ar arduino army asus augmented reality camera health monitoring advertisements code computer history 3g app cpu drone facebook flash game geolocalisation gps botnet data center picture c c++ cobol coding databse search encryption idevices protocole wifi wirelessMonday, January 27. 2014

Lightbeam for Firefox

![]()

Lightbeam, a firefox plugin you may want to try... or not... in order to have an idea about what it means for you and your privacy to browse the Web. Nowadays, this is something obvious and well spread that the 'free' Web is now a very old chimera. Web drills you the same way one drills for oil.

Collusion is a similar plugin for the Chrome Web browser.

Enjoy!

Wednesday, October 30. 2013

Facebook may start tracking your cursor as you browse the site

Via The Verge

-----

For some time Facebook has studied your Likes, comments, and clicks to help create better ads and new products, but soon, the company might also track the location of your cursor on screen. Facebook analytics chief Ken Rudin told The Wall Street Journal about several new measures the company is testing meant to help improve its user-tracking, like seeing how long you hover your cursor over an ad (and if you click it), and evaluating if certain elements on screen are within view or are off the page. New data gathered using these methods could help Facebook create more engaging News Feed layouts and ads.

The Journal notes that this kind of tracking is hardly uncommon, but until now, Facebook hadn't gone this deep in its behavioral data measurement. Sites like Shutterstock, for example, track how long users hover their cursors over an image before deciding to buy it. Facebook is famous for its liberal use of A/B testing to try out new products on consumers, but it's using the same method to judge the efficacy of its new testing methods. "Facebook should know within months whether it makes sense to incorporate the new data collection into the business," reports the Journal.

Assuming Facebook's tests go well, it shouldn't be long before our every flinch is tracked on the site. So what might come next? Our eyeballs.

Sunday, October 20. 2013

China employs two million microblog monitors state media say

Via BBC

-----

Sina Weibo, launched in 2010, has more than 500 million registered users with 100 million messages posted daily

More than two million people in China are employed by the government to monitor web activity, state media say, providing a rare glimpse into how the state tries to control the internet.

The Beijing News says the monitors, described as internet opinion analysts, are on state and commercial payrolls.

China's hundreds of millions of web users increasingly use microblogs to criticise the state or vent anger.

Recent research suggested Chinese censors actively target social media.

The report by the Beijing News said that these monitors were not required to delete postings.

They are "strictly to gather and analyse public opinions on microblog sites and compile reports for decision-makers", it said. It also added details about how some of these monitors work.

Tang Xiaotao has been working as a monitor for less than six months, the report says, without revealing where he works.

"He sits in front of a PC every day, and opening up an application, he types in key words which are specified by clients.

"He then monitors negative opinions related to the clients, and gathers (them) and compile reports and send them to the clients," it says.

The reports says the software used in the office is even more advanced and supported by thousands of servers. It also monitors websites outside China.

China rarely reveals any details concerning the scale and sophistication of its internet police force.

It is believed that the two million internet monitors are part of a huge army which the government relies on to control the internet.

The government is also to organise training classes for them for the first time from 14 to 18 October, the paper says.

But it is not clear whether the training will be for existing monitors or for new recruits.

The training will have eight modules, and teach participants how to analyse and judge online postings and deal with crisis situations, it says.

The most popular microblogging site Sina Weibo, launched in 2010, now has more than 500 million registered users with 100 million messages posted daily.

Topics cover a wide range - from personal hobbies, health to celebrity gossip and food safety but they talso include politically sensitive issues like official corruption.

Postings deemed to be politically incorrect are routinely deleted.

Wednesday, October 16. 2013

What Big Data Knows About Us

Via Mashable

-----

The world of Big Data is one of pervasive data collection and aggressive analytics. Some see the future and cheer it on; others rebel. Behind it all lurks a question most of us are asking — does it really matter? I had a chance to find out recently, as I got to see what Acxiom, a large-scale commercial data aggregator, had collected about me.

At least in theory large-scale data collection matters quite a bit. Large data sets can be used to create social network maps and can form the seeds for link analysis of connections between individuals. Some see this as a good thing; others as a bad one — but whatever your viewpoint, we live in a world which sees increasing power and utility in Big Data’s large-scale data sets.

Of course, much of the concern is about government collection. But it’s difficult to assess just how useful this sort of data collection by the government is because, of course, most governmental data collection projects are classified. The good news, however, is that we can begin to test the utility of the program in the private sector arena. A useful analog in the private sector just became publicly available and it’s both moderately amusing and instructive to use it as a lens for thinking about Big Data.

Acxiom is one of the largest commercial, private sector data aggregators around. It collects and sells large data sets about consumers — sometimes even to the government. And for years it did so quietly, behind the scene — as one writer put it “mapping the consumer genome.” Some saw this as rather ominous; others as just curious. But it was, for all of us, mysterious. Until now.

In September, the data giant made available to the public a portion of its data set. They created a new website — Abouthedata.com — where a consumer could go to see what data the company had collected about them. Of course, in order to access the data about yourself you had to first verify your own identity (I had to send in a photocopy of my driver’s license), but once you had done so, it would be possible to see, in broad terms, what the company thought it knew about you — and how close that knowledge was to reality.

I was curious, so I thought I would go explore myself and see what it was they knew and how accurate they were. The results were at times interesting, illuminating and mundane. Here are a few observations:

To begin with, the fundamental purpose of the data collection is to sell me things — that’s what potential sellers want to know about potential buyers and what, say, Amazon might want to know about me. So I first went and looked at a category called “Household Purchase Data” — in other words what I had recently bought.

It turns out that I buy … well … everything. I buy food, beverages, art, computing equipment, magazines, men’s clothing, stationary, health products, electronic products, sports and leisure products, and so forth. In other words, my purchasing habits were, to Acxiom, just an undifferentiated mass. Save for the notation that I had bought an antique in the past and that I have purchased “High Ticket Merchandise,” it seems that almost everything I bought was something that most any moderately well-to-do consumer would buy.

I do suppose that the wide variety of purchases I made is, itself, the point — by purchasing so widely I self-identify as a “good” consumer. But if that’s the point then the data set seems to miss the mark on “how good” I really am. Under the category of “total dollars spent,” for example, it said that I had spent just $1,898 in the past two years. Without disclosing too much about my spending habits in this public forum, I think it is fair to say that this is a significant underestimate of my purchasing activity.

The next data category of “Household Interests” was equally unilluminating. Acxiom correctly said I was interested in computers, arts, cooking, reading and the like. It noted that I was interested in children’s items (for my grandkids) and beauty items and gardening (both my wife’s interest, probably confused with mine). Here, as well, there was little differentiation, and I assume the breadth of my interests is what matters rather that the details. So, as a consumer, examining what was collected about me seemed to disclose only a fairly anodyne level of detail.

[Though I must object to the suggestion that I am an Apple user J. Anyone who knows me knows I prefer the Windows OS. I assume this was also the result of confusion within the household and a reflection of my wife’s Apple use. As an aside, I was invited throughout to correct any data that was in error. This I chose not to do, as I did not want to validate data for Acxiom – that’s their job not mine—and I had no real interest in enhancing their ability to sell me to other marketers. On the other hand I also did not take the opportunity they offered to completely opt-out of their data system, on the theory that a moderate amount of data in the world about me may actually lead to being offered some things I want to purchase.]

Things became a bit more intrusive (and interesting) when I started to look at my “Characteristic Data” — that is data about who I am. Some of the mistakes were a bit laughable — they pegged me as of German ethnicity (because of my last name, naturally) when, with all due respect to my many German friends, that isn’t something I’d ever say about myself. And they got my birthday wrong — lord knows why.

But some of their insights were at least moderately invasive of my privacy, and highly accurate. Acxiom “inferred” for example, that I’m married. They identified me accurately as a Republican (but notably not necessarily based on voter registration — instead it was the party I was “associated with by voter registration or as a supporter”). They knew there were no children in my household (all grown up) and that I run a small business and frequently work from home. And they knew which sorts of charities we supported (from surveys, online registrations and purchasing activity). Pretty accurate, I’d say.

Finally, it was completely unsurprising that the most accurate data about me was closely related to the most easily measurable and widely reported aspect of my life (at least in the digital world) — namely, my willingness to dive into the digital financial marketplace.

Acxiom knew that I had several credit cards and used them regularly. It had a broadly accurate understanding of my household total income range [I’m not saying!].Acxiom knew that I had several credit cards and used them regularly.

They also knew all about my house — which makes sense since real estate and liens are all matters of public record. They knew I was a home owner and what the assessed value was. The data showed, accurately, that I had a single family dwelling and that I’d lived there longer than 14 years. It disclosed how old my house was (though with the rather imprecise range of having been built between 1900 and 1940). And, of course, they knew what my mortgage was, and thus had a good estimate of the equity I had in my home.

So what did I learn from this exercise?

In some ways, very little. Nothing in the database surprised me, and the level of detail was only somewhat discomfiting. Indeed, I was more struck by how uninformative the database was than how detailed it was — what, after all, does anyone learn by knowing that I like to read? Perhaps Amazon will push me book ads, but they already know I like to read because I buy directly from them. If they had asserted that I like science fiction novels or romantic comedy movies, that level of detail might have demonstrated a deeper grasp of who I am — but that I read at all seems pretty trivial information about me.

I do, of course, understand that Acxiom has not completely lifted the curtains on its data holdings. All we see at About The Data is summary information. You don’t get to look at the underlying data elements. But even so, if that’s the best they can do ….

In fact, what struck me most forcefully was (to borrow a phrase from Hannah Arendt) the banality of it all. Some, like me, see great promise in big data analytics as a way of identifying terrorists or tracking disease. Others, with greater privacy concerns, look at big data and see Big Brother. But when I dove into one big data set (albeit only partially), held by one of the largest data aggregators in the world, all I really became was a bit bored.

Maybe that’s what they wanted as a way of reassuring me. If so, Acxiom succeeded, in spades.

Tuesday, October 01. 2013

France sanctions Google for European privacy law violations

Via pcworld

-----

Google faces financial sanctions in France after failing to comply with an order to alter how it stores and shares user data to conform to the nation's privacy laws.

The enforcement follows an analysis led by European data protection authorities of a new privacy policy that Google enacted in 2012, France's privacy watchdog, the Commission Nationale de L'Informatique et des Libertes, said Friday on its website.

Google was ordered in June by the CNIL to comply with French data protection laws within three months. But Google had not changed its policies to comply with French laws by a deadline on Friday, because the company said that France's data protection laws did not apply to users of certain Google services in France, the CNIL said.

The company "has not implemented the requested changes," the CNIL said.

As a result, "the chair of the CNIL will now designate a rapporteur for the purpose of initiating a formal procedure for imposing sanctions, according to the provisions laid down in the French data protection law," the watchdog said. Google could be fined a maximum of €150,000 ($202,562), or €300,000 for a second offense, and could in some circumstances be ordered to refrain from processing personal data in certain ways for three months.

What bothers France

The CNIL took issue with several areas of Google's data policies, in particular how the company stores and uses people's data. How Google informs users about data that it processes and obtains consent from users before storing tracking cookies were cited as areas of concern by the CNIL.

In a statement, Google said that its privacy policy respects European law. "We have engaged fully with the CNIL throughout this process, and we'll continue to do so going forward," a spokeswoman said.

Google is also embroiled with European authorities in an antitrust case for allegedly breaking competition rules. The company recently submitted proposals to avoid fines in that case.

Saturday, September 28. 2013

Google Improves Knowledge Graph With Comparisons And Filters, Brings Cards & Cross-Platform Notifications To Mobile

Via TechCrunch

-----

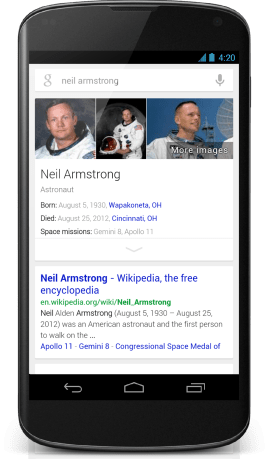

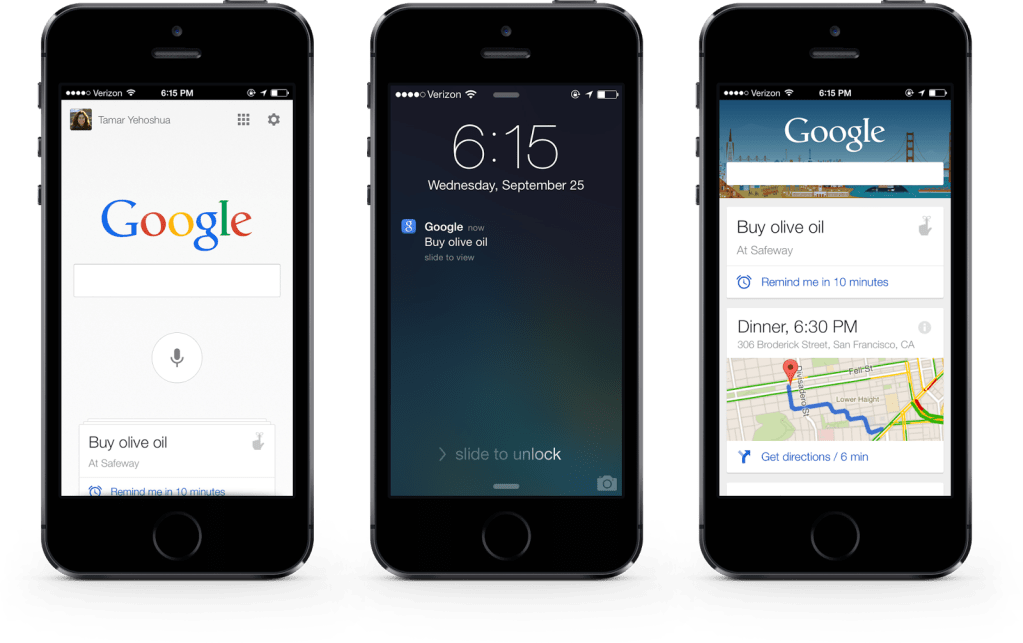

Google is turning 15 tomorrow and, fittingly, it’s celebrating the occasion by announcing a couple of new features for Google Search. The mobile search interface, for example, is about to get a bit of a redesign with results that are clustered on cards “so you can focus on the answers you’re looking for.”

Those answers, Google today announced, are also getting better. Thanks to its Knowledge Graph, the company continues to push to give users answers instead of just links, and with today’s update, it’s now featuring the ability to use the Knowledge Graph to compare things. If you want to compare the nutritional value of olive oil to butter, for example, Google Search will now give you a comparison chart with lots of details. The same holds true for other things, including dog breed and celestial objects. Google says it plans to expand this feature to more things over time.

Also new in this update is the ability to use Knowledge Graph to filter results. Say you ask Google: “Tell me about Impressionist artists.” Now, you’ll see who these artists are, and a new bar on top of the results will allow you dive in to learn more about them and to switch to learn more about abstract art, for example.

On mobile, Google is now making it easier to use your voice to set reminders and have those synced between devices. So you can say “Ok Google, Remind me to buy butter at Safeway” on your Nexus tablet and when you walk into the store with your iPhone, you’ll get that reminder. To enable this, Google will roll out a new version of its Search app for iPhone and iPad in the next few weeks.

With regard to notifications, it’s also worth noting that Google is now adding Google Now push notifications to its iPhone app, which will finally make Google Now useful on Apple’s platform.

Thursday, August 29. 2013

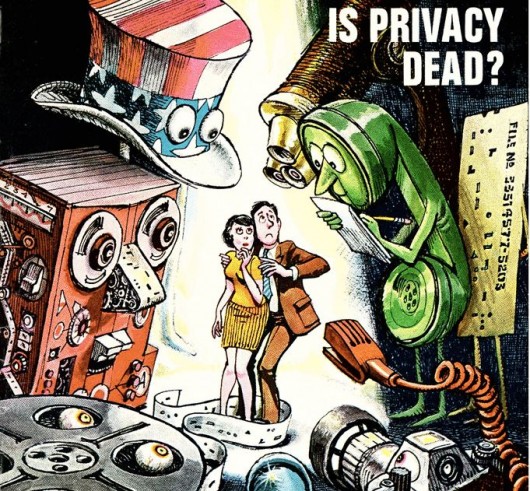

GRENIER – En 1970, Newsweek s’inquiétait de « la mort de la vie privée »

Via Le Monde Blog

-----

Couverture de "Newsweek" du 27 juillet 1970.

C'est une édition du 27 juillet 1970, du magazine américain Newsweek, titrée "La vie privée est-elle morte ?", et repérée par le Daily Beast. Dedans, un article de six pages, qui montre que les inquiétudes soulevées par les révélations sur la surveillance, par l'Agence américaine de la sécurité, des données personnelles des internautes et des communications téléphoniques ne datent pas d'hier. Même, elles apparaissent dès lors comme le dernier rebondissement masquant une tendance plus longue.

En 1970 donc, Newsweek expliquait que "durant les vingt dernières années, les Etats-Unis sont devenus (…) l'un des pays qui espionnent le plus et sont le plus soucieux de ses données dans l'histoire mondiale. Les gros commerçants, les petits commerçants, l'administration fiscale, les institutions de police, les organismes de recensement, les sociologues, les banques, les écoles, les centres médicaux, les patrons, les agences fédérales, les compagnies d'assurance (…), tous cherchent obstinément, stockent et utilisent chaque parcelle d'information qu'ils peuvent trouver sur chacun des 205 millions d'Américains, individus et groupes". Bref, "très bientôt, toute la vie et l'histoire d'une personne va être disponible en un clic sur un ordinateur. On va finir en 1984 avant d'avoir atteint cette année", prévoyait, à cette époque, un juriste américain.

>> Lire la note de Big Browser : "Le scandale de la surveillance des données personnelles booste les ventes de "1984'"

L'article énumère une série d'anecdotes où s'entrechoquent collectes de données pour la sécurité et protection de la vie privée. Par exemple, cette bibliothécaire qui a reçu une visite d'employés de l'IRS, l'agence américaine chargée des impôts, lui demandant de lui fournir les noms des "utilisateurs de matériel militant et subversif" – ouvrage sur les explosifs ou biographie du Che Guevara. Ou ce fichier de l'armée fichant les "potentiels perturbateurs ostensibles de la paix", "en plus des 7 millions de fichiers de routine" sur la loyauté ou le statut criminel des citoyens.

Le chapitre sur les écoutes téléphoniques est tout aussi parlant : les écoutes légales, "prudemment utilisées pendant la seconde guerre mondiale pour pister les espions et les saboteurs, sont devenues une pratique si banale du FBI et de la police à la fin des années 1950 qu'elles étaient menées, dit-on, contre chaque bookmaker du coin". A la suite de l'indignation de certains politiques, "le Congrès a spécifié en 1968 que le département de justice, le FBI et la police ne pouvaient pratiquer la surveillance électronique qu'avec un ordre de justice". Mais le gouvernement fédéral se réserve toujours le droit de faire des écoutes clandestines, sans ordre de justice, dans l'intérêt de la "sécurité nationale", explique Newsweek. Avant de préciser – de manière un peu incongrue, vu d'aujourd'hui : "La méfiance grandissante envers le téléphone représente la seule protection réelle de la vie privée."

En parallèle de ce vaste mouvement de collecte des données, les Américains sont devenus de plus en plus sensibles à leur droit à la protection de leur vie privée, explique l'hebdomadaire. Ce qui n'empêche pas, aujourd'hui, une majorité d'entre eux d'approuver la surveillance des communications téléphoniques, et 62 % d'estimer qu'il est important que le gouvernement fédéral enquête sur d'éventuelles menaces "terroristes", quitte à empiéter sur la vie privée, selon un sondage publié le 10 juin.

Saturday, June 29. 2013

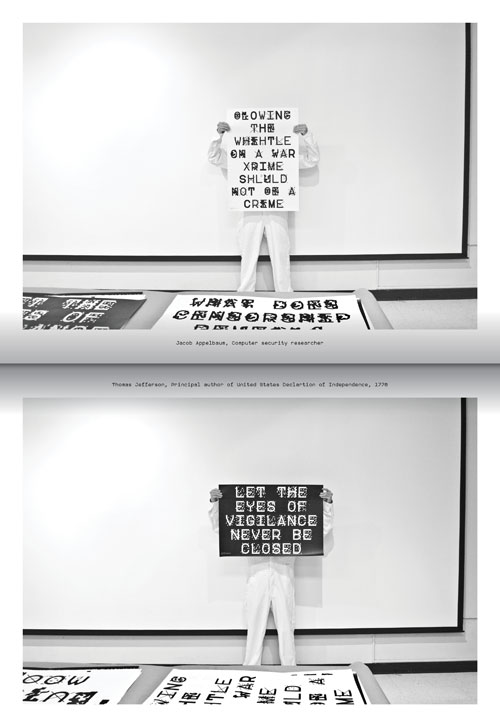

Jumbled Up, No Detection Font Prevents Infringement of Privacy

Via TAXI

-----

Fed up with the NSA’s infringement of privacy, an internet user by the name of Sang Mun has developed a font which cannot be read by computers.

Called ‘ZXX’, which is used by the Library of Congress to

state that a document has “no linguistic content”, the font is garbled

up in such a way that computers with Optical Character Recognition (OCR)

will not be able to recognize it.

Available in four “disguises”, this font uses camouflage

techniques to trick the computers of governments and corporations into

thinking that no useful information can be collated from people, while

remaining readable to the human eye.

The font developer urges users to fight against this infringement of privacy, and has made this font free for all users on his website.

Thursday, December 06. 2012

Temporary tatto as a medical sensor

Via FUTURITY

-----

A medical sensor that attaches to the skin like a temporary tattoo could make it easier for doctors to detect metabolic problems in patients and for coaches to fine-tune athletes’ training routines. And the entire sensor comes in a thin, flexible package shaped like a smiley face. (Credit: University of Toronto)

It looks like a smiley face tattoo, but a new easy-to-apply sensor can detect medical problems and help athletes fine-tune training routines.

“We wanted a design that could conceal the electrodes,” says Vinci Hung, a PhD candidate in physical and environmental sciences at the University of Toronto, who helped create the new sensor. “We also wanted to showcase the variety of designs that can be accomplished with this fabrication technique.”

The tattoo, which is an ion-selective electrode (ISE), is made using standard screen printing technique and commercially available transfer tattoo paper—the same kind of paper that usually carries tattoos of Spiderman or Disney princesses.

In the case of the sensor, the “eyes” function as the working and reference electrodes, and the “ears” are contacts for a measurement device to connect to.

Hung contributed to the work while in the lab of Joseph Wang, a professor at the University of California, San Diego. The sensor she helped make can detect changes in the skin’s pH levels in response to metabolic stress from exertion.

Similar devices are already used by medical researchers and athletic trainers. They can give clues to underlying metabolic diseases such as Addison’s disease, or simply signal whether an athlete is fatigued or dehydrated during training. The devices are also useful in the cosmetics industry for monitoring skin secretions.

But existing devices can be bulky or hard to keep adhered to sweating skin. The new tattoo-based sensor stayed in place during tests, and continued to work even when the people wearing them were exercising and sweating extensively.

The tattoos were applied in a similar way to regular transfer tattoos, right down to using a paper towel soaked in warm water to remove the base paper.

To make the sensors, Hung and colleagues used a standard screen printer to lay down consecutive layers of silver, carbon fiber-modified carbon and insulator inks, followed by electropolymerization of aniline to complete the sensing surface.

By using different sensing materials, the tattoos can also be modified to detect other components of sweat, such as sodium, potassium, or magnesium, all of which are of potential interest to researchers in medicine and cosmetology.

An article describing the work has been accepted for publication in the journal Analyst.

Wednesday, November 28. 2012

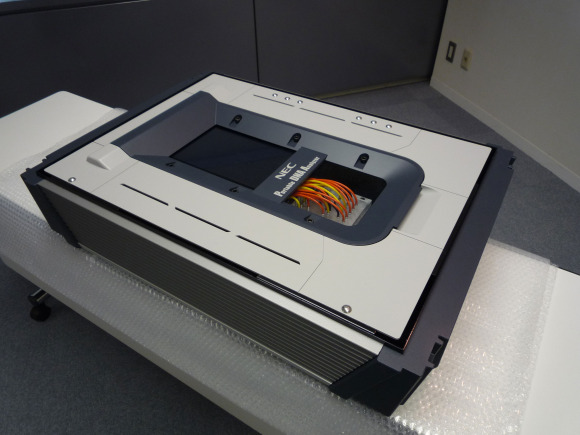

NEC is working on a suitcase-sized DNA analyzer

Via PCWorld

-----

NEC is working on a suitcase-sized DNA analyzer, which it says will be able to process samples at the scene of a crime or disaster in as little as 25 minutes.

The company said it aims to launch the device globally in 2014, and sell it for around 10 million yen, or US$120,000. It will output samples that can be quickly matched via the growing number of DNA databases worldwide.

“At first we will target investigative organizations, like police,” said spokeswoman Marita Takahashi. “We will also push its use on victims of natural disasters, to quickly match samples from siblings and parents.”

NEC hopes to use research and software from its mature fingerprint and facial matching technology, which have been deployed in everyday devices such as smartphones and ATMs.

The company said that the need for cheaper and faster DNA testing became clear in the aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that devasted much of Japan’s northeast coastline last year, when authorities performed nearly 20,000 samples.

NEC pointed to growing databases such as CODIS (Combined DNA Index System) in the U.S. and a Japanese database of DNA samples.

The company said it is aiming to make the device usable for those with minimal training, requiring only a cotton swab or small blood sample. NEC aims to make a device that weighs around 35 kilograms, measuring 850 millimeters by 552mm by 240mm, about the size of a large suitcase. The unit will run on a 12V power source.

NEC said it will be able to complete three-stage analysis process using a “lab on a chip” process, a term for for technology that recreates lab processes on chip-sized components. The basic steps for analysis include extracting DNA from samples, amplifying the DNA for analysis, and then separating out the different DNA strands.

The current version of the analyzer takes about an hour for all three tasks, and NEC said it aims to lower that to 25 minutes.

NEC it is carrying out the development of the analyzer together with partners including Promega, a U.S. biotechnology firm, and is testing it with a police science research institute in Japan.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131054)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101667)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100064)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57896)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57461)

Categories

Show tagged entries

Syndicate This Blog

Calendar

|

|

February '26 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |