Tuesday, December 18. 2012

Depixelizing pixel art

-----

Naïve upsampling of pixel art images leads to unsatisfactory results.

Our algorithm extracts a smooth, resolution-independent vector

representation from the image which is suitable for high-resolution

display devices (Image © Nintendo Co., Ltd.).

Abstract

We describe a novel algorithm for extracting a resolution-independent vector representation from pixel art

images, which enables magnifying the results by an arbitrary amount

without image degradation. Our algorithm resolves pixel-scale features

in the input and converts them into regions with smoothly varying

shading that are crisply separated by piecewise-smooth contour curves.

In the original image, pixels are represented on a square pixel lattice,

where diagonal neighbors are only connected through a single point.

This causes thin features to become visually disconnected under

magnification by conventional means, and it causes connectedness and

separation of diagonal neighbors to be ambiguous. The key to our

algorithm is in resolving these ambiguities. This enables us to reshape

the pixel cells so that neighboring pixels belonging to the same feature

are connected through edges, thereby preserving the feature

connectivity under magnification. We reduce pixel aliasing artifacts and

improve smoothness by fitting spline curves to contours in the image

and optimizing their control points.

Paper

Paper

Full Resolution (4.16 MB)

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Click here

Wednesday, December 12. 2012

Why the world is arguing over who runs the internet

Via NewScientist

-----

The ethos of freedom from control that underpins the web is facing its first serious test, says Wendy M. Grossman

WHO runs the internet? For the past 30 years, pretty much no one. Some governments might call this a bug, but to the engineers who designed the protocols, standards, naming and numbering systems of the internet, it's a feature.

The goal was to build a network that could withstand damage and would enable the sharing of information. In that, they clearly succeeded - hence the oft-repeated line from John Gilmore, founder of digital rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation: "The internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around it." These pioneers also created a robust platform on which a guy in a dorm room could build a business that serves a billion people.

But perhaps not for much longer. This week, 2000 people have gathered for the World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT) in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates to discuss, in part, whether they should be in charge.

The stated goal of the Dubai meeting is to update the obscure International Telecommunications Regulations (ITRs), last revised in 1988. These relate to the way international telecom providers operate. In charge of this process is the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), an agency set up in 1865 with the advent of the telegraph. Its $200 million annual budget is mainly funded by membership fees from 193 countries and about 700 companies. Civil society groups are only represented if their governments choose to include them in their delegations. Some do, some don't. This is part of the controversy: the WCIT is effectively a closed shop.

Vinton Cerf, Google's chief internet evangelist and co-inventor of the TCP/IP internet protocols, wrote in May that decisions in Dubai "have the potential to put government handcuffs on the net".

The need to update the ITRs isn't surprising. Consider what has happened since 1988: the internet, Wi-Fi, broadband, successive generations of mobile telephony, international data centres, cloud computing. In 1988, there were a handful of telephone companies - now there are thousands of relevant providers.

Controversy surrounding the WCIT gathering has been building for months. In May, 30 digital and human rights organisations from all over the world wrote to the ITU with three demands: first, that it publicly release all preparatory documents and proposals; second, that it open the process to civil society; and third that it ask member states to solicit input from all interested groups at national level. In June, two academics at George Mason University in Virginia - Jerry Brito and Eli Dourado - set up the WCITLeaks site, soliciting copies of the WCIT documents and posting those they received. There were still gaps in late November when .nxt, a consultancy firm and ITU member, broke ranks and posted the lot on its own site.

The issue entered the mainstream when Greenpeace and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) launched the Stop the Net Grab campaign, demanding that the WCIT be opened up to outsiders. At the launch of the campaign on 12 November, Sharan Burrow, general secretary of the ITUC, pledged to fight for as long it took to ensure an open debate on whether regulation was necessary. "We will stay the distance," she said.

This marks the first time that such large, experienced, international campaigners, whose primary work has nothing to do with the internet, have sought to protect its freedoms. This shows how fundamental a technology the internet has become.

A week later, the European parliament passed a resolution stating that the ITU was "not the appropriate body to assert regulatory authority over either internet governance or internet traffic flows", opposing any efforts to extend the ITU's scope and insisting that its human rights principles took precedence. The US has always argued against regulation.

Efforts by ITU secretary general Hamadoun Touré to spread calm have largely failed. In October, he argued that extending the internet to the two-thirds of the world currently without access required the UN's leadership. Elsewhere, he has repeatedly claimed that the more radical proposals on the table in Dubai would not be passed because they would require consensus.

These proposals raise two key fears for digital rights campaigners. The first concerns censorship and surveillance: some nations, such as Russia, favour regulation as a way to control or monitor content transiting their networks.

The second is financial. Traditional international calls attract settlement fees, which are paid by the operator in the originating country to the operator in the terminating country for completing the call. On the internet, everyone simply pays for their part of the network, and ISPs do not charge to carry each other's traffic. These arrangements underpin network neutrality, the principle that all packets are delivered equally on a "best efforts" basis. Regulation to bring in settlement costs would end today's free-for-all, in which anyone may set up a site without permission. Small wonder that Google is one of the most vocal anti-WCIT campaigners.

How worried should we be? Well, the ITU cannot enforce its decisions, but, as was pointed out at the Stop the Net Grab launch, the system is so thoroughly interconnected that there is plenty of scope for damage if a few countries decide to adopt any new regulatory measures.

This is why so many people want to be represented in a dull, lengthy process run by an organisation that may be outdated to revise regulations that can be safely ignored. If you're not in the room you can't stop the bad stuff.

Wendy M. Grossman is a science writer and the author of net.wars (NYU Press)

Tuesday, December 11. 2012

IBM silicon nanophotonics speeds servers with 25Gbps light

Via Slash Gear

-----

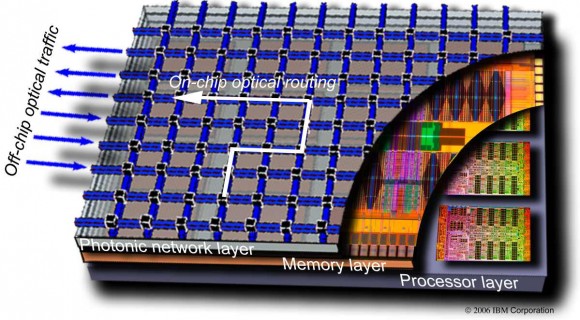

IBM has developed a light-based data transfer system delivering more than 25Gbps per channel, opening the door to chip-dense slabs of processing power that could speed up server performance, the internet, and more. The company’s research into silicon integrated nanophotonics addresses concerns that interconnects between increasingly powerful computers, such as mainframe servers, are unable to keep up with the speeds of the computers themselves. Instead of copper or even optical cables, IBM envisages on-chip optical routing, where light blasts data between dense, multi-layer computing hubs.

“This future 3D-integated chip consists of several layers connected with each other with very dense and small pitch interlayer vias. The lower layer is a processor itself with many hundreds of individual cores. Memory layer (or layers) are bonded on top to provide fast access to local caches. On top of the stack is the Photonic layer with many thousands of individual optical devices (modulators, detectors, switches) as well as analogue electrical circuits (amplifiers, drivers, latches, etc.). The key role of a photonic layer is not only to provide point-to-point broad bandwidth optical link between different cores and/or the off-chip traffic, but also to route this traffic with an array of nanophotonic switches. Hence it is named Intra-chip optical network (ICON)” IBM

Optical interconnects are increasingly being used to link different server nodes, but by bringing the individual nodes into a single stack the delays involved in communication could be pared back even further. Off-chip optical communications would also be supported, to link the data-rich hubs together.

Although the photonics system would be considerably faster than existing links – it supports multiplexing, joining multiple 25Gbps+ connections into one cable thanks to light wavelength splitting – IBM says it would also be cheaper thanks to straightforward manufacturing integration:

“By adding a few processing modules into a high-performance 90nm CMOS fabrication line, a variety of silicon nanophotonics components such as wavelength division multiplexers (WDM), modulators, and detectors are integrated side-by-side with a CMOS electrical circuitry. As a result, single-chip optical communications transceivers can be manufactured in a conventional semiconductor foundry, providing significant cost reduction over traditional approaches” IBM

Technologies like the co-developed Thunderbolt from Intel and Apple have promised affordable light-based computing connections, but so far rely on more traditional copper-based links with optical versions further down the line. IBM says its system is “primed for commercial development” though warns it may take a few years before products could actually go on sale.

Monday, December 10. 2012

MoMA adds 14 videogames to its collection – what do the devs involved think?

Via Edge

-----

The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) last week announced that it is bolstering its collection of work with 14 videogames, and plans to acquire a further 26 over the next few years. And that’s just for starters. The games will join the likes of Hector Guimard’s Paris Metro entrances, the Rubik’s Cube, M&Ms and Apple’s first iPod in the museum’s Architecture & Design department.

The move recognises the design achievements behind each creation, of course, but despite MoMA’s savvy curatorial decision, the institution risks becoming a catalyst for yet another wave of awkward ‘are games art?’ blog posts. And it doesn’t exactly go out of its way to avoid that particular quagmire in the official announcement.

“Are video games art? They sure are,” it begins, worryingly, before switching to a more considered tack, “but they are also design, and a design approach is what we chose for this new foray into this universe. The games are selected as outstanding examples of interaction design — a field that MoMA has already explored and collected extensively, and one of the most important and oft-discussed expressions of contemporary design creativity.”

MoMA worked with scholars, digital conservation and legal experts, historians and critics to come up with its criteria and final list of games, and among the yardsticks the museum looked at for inclusion are the visual quality and aesthetic experience of each game, the ways in which the game manipulates or stimulates player behaviour, and even the elegance of its code.

That initial list of 14 games makes for convincing reading, too: Pac-Man, Tetris, Another World, Myst, SimCity 2000, Vib-Ribbon, The Sims, Katamari Damacy, Eve Online, Dwarf Fortress, Portal, flOw, Passage and Canabalt.

But the wishlist also extends to Spacewar!, a selection of Magnavox Odyssey games, Pong, Snake, Space Invaders, Asteroids, Zork, Tempest, Donkey Kong, Yars’ Revenge, M.U.L.E, Core War, Marble Madness, Super Mario Bros, The Legend Of Zelda, NetHack, Street Fighter II, Chrono Trigger, Super Mario 64, Grim Fandango, Animal Crossing, and, of course, Minecraft.

Art, design or otherwise, MoMA’s focused collection is an uncommonly informed and well-considered list. And their inclusion within MoMA’s hallowed walls, and the recognition of their cultural and historical relevance that is implied, is certainly a boon for videogames on the whole. But reactions to the move have been mixed. The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones posted a blog last week titled Sorry MoMA, Videogames Are Not Art, in which he suggests that exhibiting Pac-Man and Tetris alongside work by Picasso and Van Gogh will mean “game over for any real understanding of art”.

“The worlds created by electronic games are more like playgrounds where experience is created by the interaction between a player and a programme,” he writes. “The player cannot claim to impose a personal vision of life on the game, while the creator of the game has ceded that responsibility. No one ‘owns’ the game, so there is no artist, and therefore no work of art.”

While he clearly misunderstands the capacity of a game to manifest the personal – and singular – vision of its creator, he nonetheless raises valid fears that the creative motivations behind many videogames’ – predominantly commercially-driven entertainment – are incompatible with those of serious art and that their inclusion in established museums risks muddying its definition. But while many commentators have fallen into the same trap of invoking comparisons with cubist and impressionist painters, MoMA has drawn no such parallels.

“We have to keep in mind it’s the design collection that is snapping up video games,” Passage creator Jason Rorher tells us when we put the question to him. “This is the same collection that houses Lego, teapots, and barstools. I’m happy with that, because I primarily think of myself as a designer. But sadly, even the mightiest games in this acquisition look silly when stood up next to serious works of art. I mean what’s the artistic payload of, Passage? ‘You’re gonna die someday.’ You can’t find a sentiment that’s more artistically worn out than that.”

But while he doesn’t see these games’ inclusion as a significant landmark – in fact, he even raises concerns over bandwagon-hopping – he’s still elated to have been included.

“I’m shocked to see my little game standing there next to landmarks like Pac-Man, Tetris, Another World, and… all of them really, all the way up to Canabalt,” he says. “The most pleasing aspect of it, for me, is that something I have made will be preserved and maintained into the future, after I croak. The ephemeral nature of digital-download video games has always worried me. Heck, the Mac version of Passage has already been broken by Apple’s updates, and it’s only been five years!”

Talking of Canabalt, creator Adam Saltsman echoes Rohrer’s sentiment: “Obviously it is a pretty huge honour, but I think it’s also important to note that these selections are part of the design wing of the museum, so Tetris won’t exactly be right next to Dali or Picasso! That doesn’t really diminish the excitement for me though. The MoMA is an incredible institution, and to have my work selected for archival alongside obvious masterpieces like Tetris is pretty overwhelming. “

MoMA’s not the only art institution with an interest in videogames, of course. The Smithsonian American Art Museum ran an exhibition titled The Art of Video Games earlier this year, while the Barbican has put its weight behind all manner of events, including 2002?s The History, Culture and Future of Computer Games, Ear Candy: Video Game Music, and the touring Game On exhibition.

Chris Melissinos, who was one of the guest curators who put the Smithsonian exhibition together and subsequently acted as an adviser to MoMA as it selected its list, doesn’t think such interest is damaging to art, or indeed a sign of out-of-step institutions jumping on the bandwagon. It’s simply, he believes, a reaction to today’s culture.

“This decision indicates that videogames have become an important cultural, artistic form of expression in society,” he told the Independent. “It could become one of the most important forms of artistic expression. People who apply themselves to the craft view themselves as [artists], because they absolutely are. This is an amalgam of many traditional forms of art.”

Of the initial selection, Eve is arguably the most ambitious, and potentially divisive, selection, but perhaps also the best placed to challenge Jones’ predispositions on experiential ownership and creative limitation. It is, after all, renowned for its vociferous, self-governing player community.

“Eve’s been around for close to a decade, is still growing, and through its lifetime has won several awards and achievements, but being acquired into the permanent collection of a world leading contemporary art and design museum is a tremendous honour for us,” Eve Online creative director Torfi Frans Ólafsson tells us. “Eve is born out of a strong ideology of player empowerment and sandbox openness, which especially in our earlier days was often at the cost of accessibility and mainstream appeal.

“Sitting up there along with industrial design like the original iPod, and fancy, unergonomic lemon presses tells us that we were right to stand by our convictions, so in that sense, it’s somewhat of a vindication of our efforts.”

But how do you present an entire universe to an audience that is likely to spend a few short minutes looking at each exhibit? Developer CCP is turning to its many players for help.

“We’ve decided to capture a single day of Eve: Sunday the 9th of December,” explains Ólafsson. “Through a variety of player made videos, CCP videos, massive data analysis and info graphics.”

In presenting Eve in this way, CCP and the games players are collaborating on a strong, coherent vision of the alternative reality they’ve collectively helped to build, and more importantly, reinforcing and redefining the notion of authorship. It doesn’t matter whether you’re an apologist for videogames’ entitlement to the status of art, or someone who appreciates the aesthetics of their design, the important thing here is that their cultural importance is recognised. Sure, the notion of a game exhibit that doesn’t include gameplay might stick in the craw of some, but MoMA’s interest is clearly broader. Ólafsson isn’t too worried, either.

“Even if we don’t fully succeed in making the 3.5 million people that visit the MoMA every year visually grok the entire universe in those few minutes they might spend checking Eve out, I can promise you it sure will look pretty there on the wall.”

Personal Comments:

Passage is still available here, a game developed during Gamma256.

Canabalt is available here, while mobile versions are available for few bucks (android, iOS).

Thursday, December 06. 2012

Temporary tatto as a medical sensor

Via FUTURITY

-----

A medical sensor that attaches to the skin like a temporary tattoo could make it easier for doctors to detect metabolic problems in patients and for coaches to fine-tune athletes’ training routines. And the entire sensor comes in a thin, flexible package shaped like a smiley face. (Credit: University of Toronto)

It looks like a smiley face tattoo, but a new easy-to-apply sensor can detect medical problems and help athletes fine-tune training routines.

“We wanted a design that could conceal the electrodes,” says Vinci Hung, a PhD candidate in physical and environmental sciences at the University of Toronto, who helped create the new sensor. “We also wanted to showcase the variety of designs that can be accomplished with this fabrication technique.”

The tattoo, which is an ion-selective electrode (ISE), is made using standard screen printing technique and commercially available transfer tattoo paper—the same kind of paper that usually carries tattoos of Spiderman or Disney princesses.

In the case of the sensor, the “eyes” function as the working and reference electrodes, and the “ears” are contacts for a measurement device to connect to.

Hung contributed to the work while in the lab of Joseph Wang, a professor at the University of California, San Diego. The sensor she helped make can detect changes in the skin’s pH levels in response to metabolic stress from exertion.

Similar devices are already used by medical researchers and athletic trainers. They can give clues to underlying metabolic diseases such as Addison’s disease, or simply signal whether an athlete is fatigued or dehydrated during training. The devices are also useful in the cosmetics industry for monitoring skin secretions.

But existing devices can be bulky or hard to keep adhered to sweating skin. The new tattoo-based sensor stayed in place during tests, and continued to work even when the people wearing them were exercising and sweating extensively.

The tattoos were applied in a similar way to regular transfer tattoos, right down to using a paper towel soaked in warm water to remove the base paper.

To make the sensors, Hung and colleagues used a standard screen printer to lay down consecutive layers of silver, carbon fiber-modified carbon and insulator inks, followed by electropolymerization of aniline to complete the sensing surface.

By using different sensing materials, the tattoos can also be modified to detect other components of sweat, such as sodium, potassium, or magnesium, all of which are of potential interest to researchers in medicine and cosmetology.

An article describing the work has been accepted for publication in the journal Analyst.

Wednesday, December 05. 2012

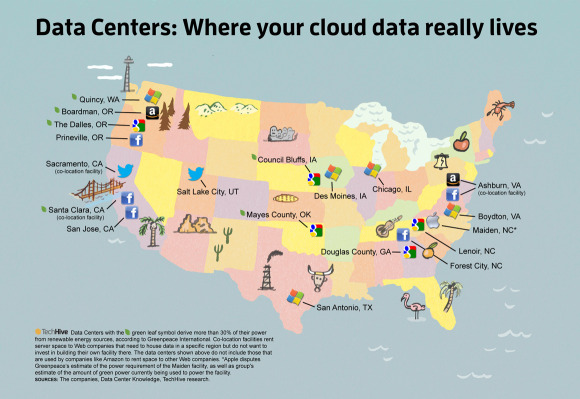

Infographic: Where your cloud data really lives

Via TechHive

-----

More and more of our data--our credit card numbers, tweets, photos, personal documents, browsing habits, music, and a hundred other things--is stored "in the cloud." The cloud metaphor evokes images of bits and bytes floating around in the ether somewhere, and we rarely hear tech companies talking about their data centers, where the data really lives.

That's partly because data centers are boring. They're typically huge concrete buildings that contain rows and rows of servers in racks, with a couple of guys who walk around looking thoughfully at little blinking lights, and then making little checkmarks on a clipboard. Another reason you don't hear much about data centers is that all those servers require huge amounts of power to run them and keep them cool—and in some cases this makes them far from green.

At any rate, the image below shows the locations of many of the major data centers that preserve your Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Twitter data.

Tuesday, December 04. 2012

The Relevance of Algorithms

By Tarleton Gillespie

-----

I’m really excited to share my new essay, “The Relevance of Algorithms,” with those of you who are interested in such things. It’s been a treat to get to think through the issues surrounding algorithms and their place in public culture and knowledge, with some of the participants in Culture Digitally (here’s the full litany: Braun, Gillespie, Striphas, Thomas, the third CD podcast, and Anderson‘s post just last week), as well as with panelists and attendees at the recent 4S and AoIR conferences, with colleagues at Microsoft Research, and with all of you who are gravitating towards these issues in their scholarship right now.

The motivation of the essay was two-fold: first, in my research on online platforms and their efforts to manage what they deem to be “bad content,” I’m finding an emerging array of algorithmic techniques being deployed: for either locating and removing sex, violence, and other offenses, or (more troublingly) for quietly choreographing some users away from questionable materials while keeping it available for others. Second, I’ve been helping to shepherd along this anthology, and wanted my contribution to be in the spirit of the its aims: to take one step back from my research to articulate an emerging issue of concern or theoretical insight that (I hope) will be of value to my colleagues in communication, sociology, science & technology studies, and information science.

The anthology will ideally be out in Fall 2013. And we’re still finalizing the subtitle. So here’s the best citation I have.

Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Relevance of Algorithms. forthcoming, in Media Technologies, ed. Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo Boczkowski, and Kirsten Foot. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Below is the introduction, to give you a taste.

Algorithms play an increasingly important role in selecting what information is considered most relevant to us, a crucial feature of our participation in public life. Search engines help us navigate massive databases of information, or the entire web. Recommendation algorithms map our preferences against others, suggesting new or forgotten bits of culture for us to encounter. Algorithms manage our interactions on social networking sites, highlighting the news of one friend while excluding another’s. Algorithms designed to calculate what is “hot” or “trending” or “most discussed” skim the cream from the seemingly boundless chatter that’s on offer. Together, these algorithms not only help us find information, they provide a means to know what there is to know and how to know it, to participate in social and political discourse, and to familiarize ourselves with the publics in which we participate. They are now a key logic governing the flows of information on which we depend, with the “power to enable and assign meaningfulness, managing how information is perceived by users, the ‘distribution of the sensible.’” (Langlois 2012)

Algorithms need not be software: in the broadest sense, they are encoded procedures for transforming input data into a desired output, based on specified calculations. The procedures name both a problem and the steps by which it should be solved. Instructions for navigation may be considered an algorithm, or the mathematical formulas required to predict the movement of a celestial body across the sky. “Algorithms do things, and their syntax embodies a command structure to enable this to happen” (Goffey 2008, 17). We might think of computers, then, fundamentally as algorithm machines — designed to store and read data, apply mathematical procedures to it in a controlled fashion, and offer new information as the output.

But as we have embraced computational tools as our primary media of expression, and have made not just mathematics but all information digital, we are subjecting human discourse and knowledge to these procedural logics that undergird all computation. And there are specific implications when we use algorithms to select what is most relevant from a corpus of data composed of traces of our activities, preferences, and expressions.

These algorithms, which I’ll call public relevance algorithms, are — by the very same mathematical procedures — producing and certifying knowledge. The algorithmic assessment of information, then, represents a particular knowledge logic, one built on specific presumptions about what knowledge is and how one should identify its most relevant components. That we are now turning to algorithms to identify what we need to know is as momentous as having relied on credentialed experts, the scientific method, common sense, or the word of God.

What we need is an interrogation of algorithms as a key feature of our information ecosystem (Anderson 2011), and of the cultural forms emerging in their shadows (Striphas 2010), with a close attention to where and in what ways the introduction of algorithms into human knowledge practices may have political ramifications. This essay is a conceptual map to do just that. I will highlight six dimensions of public relevance algorithms that have political valence:

1. Patterns of inclusion: the choices behind what makes it into an index in the first place, what is excluded, and how data is made algorithm ready

2. Cycles of anticipation: the implications of algorithm providers’ attempts to thoroughly know and predict their users, and how the conclusions they draw can matter

3. The evaluation of relevance: the criteria by which algorithms determine what is relevant, how those criteria are obscured from us, and how they enact political choices about appropriate and legitimate knowledge

4. The promise of algorithmic objectivity: the way the technical character of the algorithm is positioned as an assurance of impartiality, and how that claim is maintained in the face of controversy

5. Entanglement with practice: how users reshape their practices to suit the algorithms they depend on, and how they can turn algorithms into terrains for political contest, sometimes even to interrogate the politics of the algorithm itself

6. The production of calculated publics: how the algorithmic presentation of publics back to themselves shape a public’s sense of itself, and who is best positioned to benefit from that knowledge.

Considering how fast these technologies and the uses to which they are put are changing, this list must be taken as provisional, not exhaustive. But as I see it, these are the most important lines of inquiry into understanding algorithms as emerging tools of public knowledge and discourse.

It would also be seductively easy to get this wrong. In attempting to say something of substance about the way algorithms are shifting our public discourse, we must firmly resist putting the technology in the explanatory driver’s seat. While recent sociological study of the Internet has labored to undo the simplistic technological determinism that plagued earlier work, that determinism remains an alluring analytical stance. A sociological analysis must not conceive of algorithms as abstract, technical achievements, but must unpack the warm human and institutional choices that lie behind these cold mechanisms. I suspect that a more fruitful approach will turn as much to the sociology of knowledge as to the sociology of technology — to see how these tools are called into being by, enlisted as part of, and negotiated around collective efforts to know and be known. This might help reveal that the seemingly solid algorithm is in fact a fragile accomplishment.

~ ~ ~

Here is the full article [PDF]. Please feel free to share it, or point people to this post.

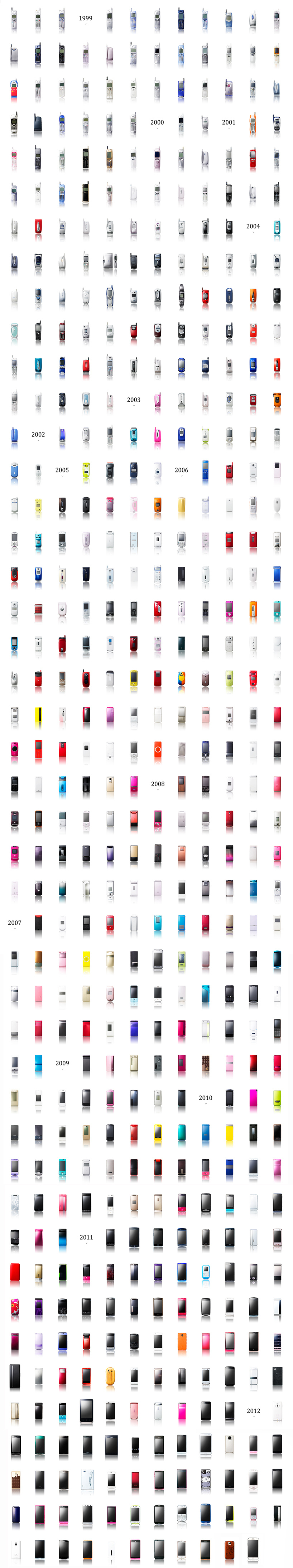

25 Years Of Cell Phones In A Single Image

Monday, December 03. 2012

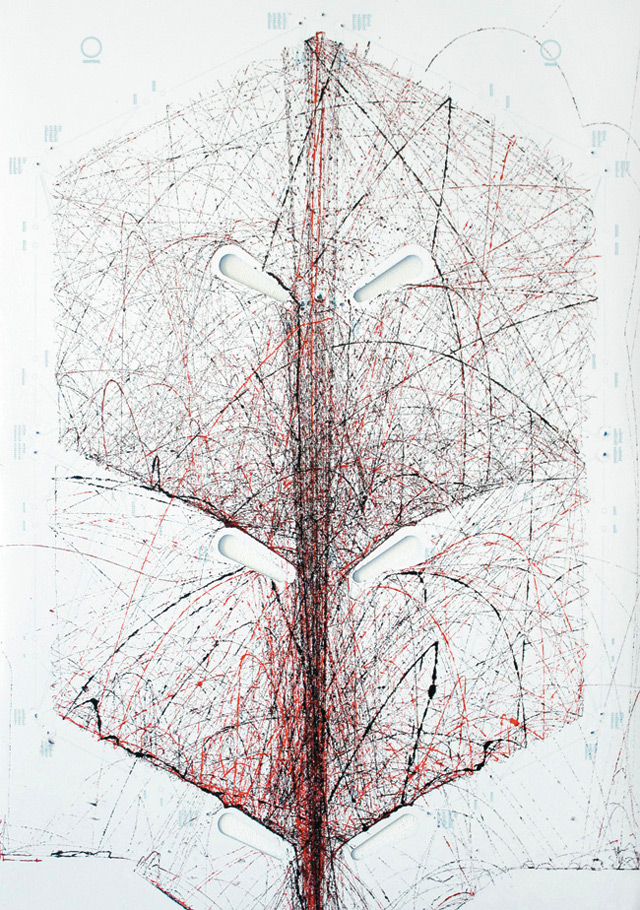

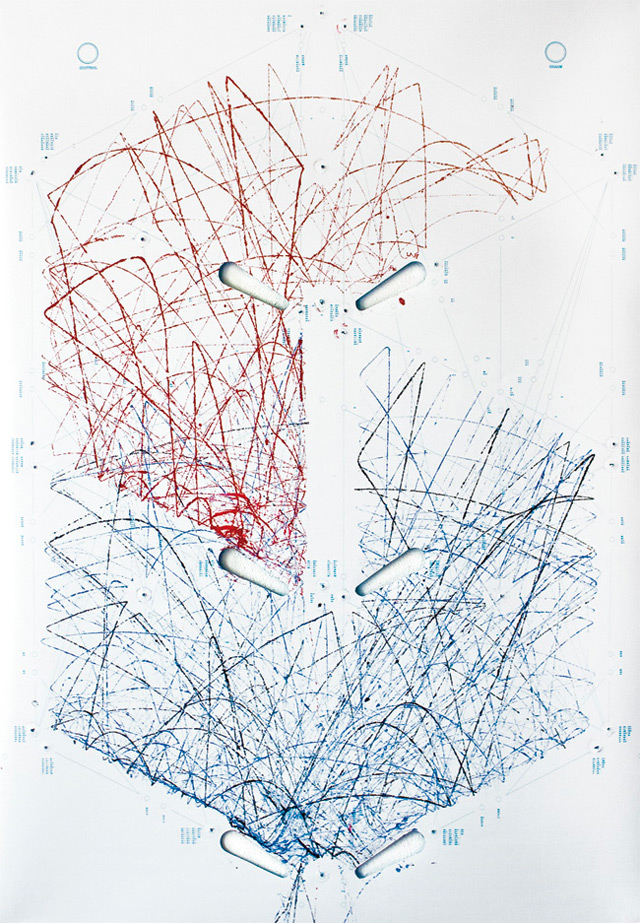

A Drawing Machine that Records the Chaos of Pinball

Via This is colossal

-----

From the pendulum-based drawing machine by Eske Rex to the art of Tim Knowles

who attaches writing implements to trees, I love when the seemingly

random lines of chaos (or maybe just physics) are rendered visible using

ink or pencil. This latest project titled STYN by Netherlands-based graduate student Sam van Doorn

is no exception. Using modified parts from an old pinball machine van

Doorn created a one-of-a-kind drawing device that utilizes standard

flippers to control a ink-covered sphere that moves across a temporary

poster placed on the game surface. He suggets that skill then becomes a

factor, as the better you are at pinball the more complex the drawing

becomes. See much more on his website, here. My drawing would have a single line that goes between the flippers and then have TILT written all over it.

Kinect like device: ASUS Xtion

Here is a Kinect-like device from ASUS, which proposed a SDK based on openNI (standard libraries that manage natural interactions issued by different kind of devices). This product can be an interesting alternative to the Microsoft Kinect device for research projects, proposing examples in C++, C# and Java.

Specifications

| Power Consumption | below 2.5W |

| Distance of Use | Between 0.8m and 3.5m |

| Field of View | 58° H, 45° V, 70° D (Horizontal, Vertical, Diagonal) |

| Sensor | RGB& Depth& Microphone*2 |

| Depth Image Size | VGA (640x480) : 30 fps QVGA (320x240): 60 fps |

| Resolution | SXGA (1280*1024) |

| Platform | Intel X86 & AMD |

| OS Support | Win 32/64 : XP , Vista, 7 Linux Ubuntu 10.10: X86,32/64 bit Android(by request) |

| Interface | USB2.0 |

| Software | software development kits(OPEN NI SDK bundled) |

| Programming Language | C++/C# (Windows) C++(Linux) JAVA |

| Operation Environment | Indoor |

| Dimensions | 18 x 3.5 x 5 cm |

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131044)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101656)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100057)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57885)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57446)