Entries tagged as programming

Related tags

3d printing 3d scanner crowd-sourcing diy evolution facial copy food hardware innovation&society medecin microsoft physical computing piracy rapid prototyping recycling robot software technology virus ai algorythm android apple arduino automation data mining data visualisation mobile network neural network sensors siri web artificial intelligence big data cloud computing coding fft program ad app google history htc ios linux mobile phone os sdk super collider tablet usb API facial recognition glass interface mirror windows 8 satellite art game car privacy super computer drone light wifi c c++ cobol fortran language lisp pascal smalltalk code flickr gui internet internet of things maps photos databse sql dna genome surveillance army cameraMonday, December 10. 2012

MoMA adds 14 videogames to its collection – what do the devs involved think?

Via Edge

-----

The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) last week announced that it is bolstering its collection of work with 14 videogames, and plans to acquire a further 26 over the next few years. And that’s just for starters. The games will join the likes of Hector Guimard’s Paris Metro entrances, the Rubik’s Cube, M&Ms and Apple’s first iPod in the museum’s Architecture & Design department.

The move recognises the design achievements behind each creation, of course, but despite MoMA’s savvy curatorial decision, the institution risks becoming a catalyst for yet another wave of awkward ‘are games art?’ blog posts. And it doesn’t exactly go out of its way to avoid that particular quagmire in the official announcement.

“Are video games art? They sure are,” it begins, worryingly, before switching to a more considered tack, “but they are also design, and a design approach is what we chose for this new foray into this universe. The games are selected as outstanding examples of interaction design — a field that MoMA has already explored and collected extensively, and one of the most important and oft-discussed expressions of contemporary design creativity.”

MoMA worked with scholars, digital conservation and legal experts, historians and critics to come up with its criteria and final list of games, and among the yardsticks the museum looked at for inclusion are the visual quality and aesthetic experience of each game, the ways in which the game manipulates or stimulates player behaviour, and even the elegance of its code.

That initial list of 14 games makes for convincing reading, too: Pac-Man, Tetris, Another World, Myst, SimCity 2000, Vib-Ribbon, The Sims, Katamari Damacy, Eve Online, Dwarf Fortress, Portal, flOw, Passage and Canabalt.

But the wishlist also extends to Spacewar!, a selection of Magnavox Odyssey games, Pong, Snake, Space Invaders, Asteroids, Zork, Tempest, Donkey Kong, Yars’ Revenge, M.U.L.E, Core War, Marble Madness, Super Mario Bros, The Legend Of Zelda, NetHack, Street Fighter II, Chrono Trigger, Super Mario 64, Grim Fandango, Animal Crossing, and, of course, Minecraft.

Art, design or otherwise, MoMA’s focused collection is an uncommonly informed and well-considered list. And their inclusion within MoMA’s hallowed walls, and the recognition of their cultural and historical relevance that is implied, is certainly a boon for videogames on the whole. But reactions to the move have been mixed. The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones posted a blog last week titled Sorry MoMA, Videogames Are Not Art, in which he suggests that exhibiting Pac-Man and Tetris alongside work by Picasso and Van Gogh will mean “game over for any real understanding of art”.

“The worlds created by electronic games are more like playgrounds where experience is created by the interaction between a player and a programme,” he writes. “The player cannot claim to impose a personal vision of life on the game, while the creator of the game has ceded that responsibility. No one ‘owns’ the game, so there is no artist, and therefore no work of art.”

While he clearly misunderstands the capacity of a game to manifest the personal – and singular – vision of its creator, he nonetheless raises valid fears that the creative motivations behind many videogames’ – predominantly commercially-driven entertainment – are incompatible with those of serious art and that their inclusion in established museums risks muddying its definition. But while many commentators have fallen into the same trap of invoking comparisons with cubist and impressionist painters, MoMA has drawn no such parallels.

“We have to keep in mind it’s the design collection that is snapping up video games,” Passage creator Jason Rorher tells us when we put the question to him. “This is the same collection that houses Lego, teapots, and barstools. I’m happy with that, because I primarily think of myself as a designer. But sadly, even the mightiest games in this acquisition look silly when stood up next to serious works of art. I mean what’s the artistic payload of, Passage? ‘You’re gonna die someday.’ You can’t find a sentiment that’s more artistically worn out than that.”

But while he doesn’t see these games’ inclusion as a significant landmark – in fact, he even raises concerns over bandwagon-hopping – he’s still elated to have been included.

“I’m shocked to see my little game standing there next to landmarks like Pac-Man, Tetris, Another World, and… all of them really, all the way up to Canabalt,” he says. “The most pleasing aspect of it, for me, is that something I have made will be preserved and maintained into the future, after I croak. The ephemeral nature of digital-download video games has always worried me. Heck, the Mac version of Passage has already been broken by Apple’s updates, and it’s only been five years!”

Talking of Canabalt, creator Adam Saltsman echoes Rohrer’s sentiment: “Obviously it is a pretty huge honour, but I think it’s also important to note that these selections are part of the design wing of the museum, so Tetris won’t exactly be right next to Dali or Picasso! That doesn’t really diminish the excitement for me though. The MoMA is an incredible institution, and to have my work selected for archival alongside obvious masterpieces like Tetris is pretty overwhelming. “

MoMA’s not the only art institution with an interest in videogames, of course. The Smithsonian American Art Museum ran an exhibition titled The Art of Video Games earlier this year, while the Barbican has put its weight behind all manner of events, including 2002?s The History, Culture and Future of Computer Games, Ear Candy: Video Game Music, and the touring Game On exhibition.

Chris Melissinos, who was one of the guest curators who put the Smithsonian exhibition together and subsequently acted as an adviser to MoMA as it selected its list, doesn’t think such interest is damaging to art, or indeed a sign of out-of-step institutions jumping on the bandwagon. It’s simply, he believes, a reaction to today’s culture.

“This decision indicates that videogames have become an important cultural, artistic form of expression in society,” he told the Independent. “It could become one of the most important forms of artistic expression. People who apply themselves to the craft view themselves as [artists], because they absolutely are. This is an amalgam of many traditional forms of art.”

Of the initial selection, Eve is arguably the most ambitious, and potentially divisive, selection, but perhaps also the best placed to challenge Jones’ predispositions on experiential ownership and creative limitation. It is, after all, renowned for its vociferous, self-governing player community.

“Eve’s been around for close to a decade, is still growing, and through its lifetime has won several awards and achievements, but being acquired into the permanent collection of a world leading contemporary art and design museum is a tremendous honour for us,” Eve Online creative director Torfi Frans Ólafsson tells us. “Eve is born out of a strong ideology of player empowerment and sandbox openness, which especially in our earlier days was often at the cost of accessibility and mainstream appeal.

“Sitting up there along with industrial design like the original iPod, and fancy, unergonomic lemon presses tells us that we were right to stand by our convictions, so in that sense, it’s somewhat of a vindication of our efforts.”

But how do you present an entire universe to an audience that is likely to spend a few short minutes looking at each exhibit? Developer CCP is turning to its many players for help.

“We’ve decided to capture a single day of Eve: Sunday the 9th of December,” explains Ólafsson. “Through a variety of player made videos, CCP videos, massive data analysis and info graphics.”

In presenting Eve in this way, CCP and the games players are collaborating on a strong, coherent vision of the alternative reality they’ve collectively helped to build, and more importantly, reinforcing and redefining the notion of authorship. It doesn’t matter whether you’re an apologist for videogames’ entitlement to the status of art, or someone who appreciates the aesthetics of their design, the important thing here is that their cultural importance is recognised. Sure, the notion of a game exhibit that doesn’t include gameplay might stick in the craw of some, but MoMA’s interest is clearly broader. Ólafsson isn’t too worried, either.

“Even if we don’t fully succeed in making the 3.5 million people that visit the MoMA every year visually grok the entire universe in those few minutes they might spend checking Eve out, I can promise you it sure will look pretty there on the wall.”

Personal Comments:

Passage is still available here, a game developed during Gamma256.

Canabalt is available here, while mobile versions are available for few bucks (android, iOS).

Monday, November 26. 2012

A Few New Things Coming To JavaScript

Via Addy Osmani

-----

I believe the day-to-day practice of writing JavaScript is going to change dramatically for the better when ECMAScript.next arrives. The coming year is going to be an exciting time for developers as features proposed or finalised for the next versions of the language start to become more widely available.

In this post, I will review some of the features I'm personally looking forward to landing and being used in 2013 and beyond.

ES.next implementation status

Be sure to look at Juriy Zaytsev's ECMAScript 6 compatibility table, Mozilla's ES6 status page as well as the bleeding edge versions of modern browsers (e.g Chrome Canary, Firefox Aurora) to find out what ES.next features are available to play with right now.

In Canary, remember that to enable all of the latest JavaScript experiments you should navigate to chrome:flags and use the 'Enable Experimental JavaScript' option.

Alternatively, many ES.next features can be experimented with using Google's Traceur transpiler (useful unit tests with examples here) and there are shims available for other features via projects such as ES6-Shim and Harmony Collections.

Finally, in Node.js (V8), the --harmony flag activates a number of experimental ES.next features including block scoping, WeakMaps and more.

Modules

We're

used to separating our code into manageable blocks of functionality. In

ES.next, A module is a unit of code contained within a module

declaration. It can either be defined inline or within an externally

loaded module file. A skeleton inline module for a Car could be written:

- module Car {

- // import …

- // export …

- }

A module instance is a module which has been evaluated, is linked to other modules or has lexically encapsulated data. An example of a module instance is:

- module myCar at "car.js";

module declarations can be used in the following contexts:

- module UniverseTest {};

- module Universe { module MilkyWay {} };

- module MilkyWay = 'Universe/MilkyWay';

- module SolarSystem = Universe.MilkyWay.SolarSystem;

- module MySystem = SolarSystem;

An export

declaration declares that a local function or variable binding is

visible externally to other modules. If familiar with the module

pattern, think of this concept as being parallel to the idea of exposing

functionality publicly.

- module Car {

- // Internal

- var licensePlateNo = '556-343';

- // External

- export function drive(speed, direction) {

- console.log('details:', speed, direction);

- }

- export module engine{

- export function check() { }

- }

- export var miles = 5000;

- export var color = 'silver';

- };

Modules import what they wish to use from other modules. Other modules may read the module exports (e.g drive(), miles etc. above) but they cannot modify them. Exports can be renamed as well so their names are different from local names.

Revisiting the export example above, we can now selectively choose what we wish to import when in another module.

We can just import drive():

- import drive from Car;

We can import drive() and miles:

- import {drive, miles} from Car;

Earlier,

we mentioned the concept of a Module Loader API. The module loader

allows us to dynamically load in scripts for consumption. Similar to import, we are able to consume anything defined as an export from such modules.

- // Signature: load(moduleURL, callback, errorCallback)

- Loader.load('car.js', function(car) {

- console.log(car.drive(500, 'north'));

- }, function(err) {

- console.log('Error:' + err);

- });

load() accepts three arguments:

moduleURL: The string representing a module URL (e.g "car.js")callback: A callback function which receives the output result of attempting to load, compile and then execute the moduleerrorCallback: A callback triggered if an error occurs during loading or compilation

Whilst

the above example seems fairly trivial to use, the Loader API is there

to provide a way to load modules in controlled contexts and actually

supports a number of different configuration options. Loader itself is a system provided instance of the API, but it's possible to create custom loaders using the Loader constructor.

What about classes?

I'm not going to be covering ES.next classes in this post in more, but for those wondering how they relate to modules, Alex Russell has previously shared a pretty readable example of how the two fit in – it's not at all about turning JavaScript into Java.

Classes in ES.next are there to provide a declarative surface for the semantics we're used to (e.g functions, prototypes) so that developer intent is expressed instead of the underlying imperative mechanics.

Here's some ES.next code for defining a widget:

- module widgets {

- // ...

- class DropDownButton extends Widget {

- constructor(attributes) {

- super(attributes);

- this.buildUI();

- }

- buildUI() {

- this.domNode.onclick = function(){

- // ...

- };

- }

- }

- }

Followed by today's de-sugared approach that ignores the semantic improvements brought by ES.next modules over the module pattern and instead emphasises our reliance of function variants:

- var widgets = (function(global) {

- // ...

- function DropDownButton(attributes) {

- Widget.call(this, attributes);

- this.buildUI();

- }

- DropDownButton.prototype = Object.create(Widget.prototype, {

- constructor: { value: DropDownButton },

- buildUI: {

- value: function(e) {

- this.domNode.onclick = function(e) {

- // ...

- }

- }

- }

- });

- })(this);

All the ES.next version does it makes the code more easy to read. What class means here is function,

or at least, one of the things we currently do with functions. If you

enjoy JavaScript and like using functions and prototypes, such sugar is

nothing to fear in the next version of JavaScript.

Where do these modules fit in with AMD?

If anything, the landscape for modularization and loading of code on the front-end has seen a wealth of hacks, abuse and experimentation, but we've been able to get by so far.

Are ES.next modules a step in

the right direction? Perhaps. My own take on them is that reading their

specs is one thing and actually using them is another. Playing with the

newer module syntax in Harmonizr, Require HM and Traceur,

you actually get used to the syntax and semantics very quickly – it

feels like using a cleaner module pattern but with access to native

loader API for any dynamic module loading required at runtime. That

said, the syntax might feel a little too much like Python for some

peoples tastes (e.g the import statements).

I'm part of the camp that believe if there's functionality developers are using broadly enough (e.g better modules), the platform (i.e the browser) should be trying to offer some of this natively and I'm not alone in feeling this way. James Burke, who was instrumental in bringing us AMD and RequireJS has previously said:

I want AMD and RequireJS to go away. They solve a real problem, but ideally the language and runtime should have similar capabilities built in. Native support should be able to cover the 80% case of RequireJS usage, to the point that no userland "module loader" library should be needed for those use cases, at least in the browser.

James has however questioned whether ES.next modules are a sufficient solution. He covered some more of his thoughts on ES.next modules back in June in ES6 Modules: Suggestions for improvement and later in Why not AMD? for anyone interested in reading more about how these modules fit in with RequireJS and AMD.

Isaac Schlueter has also previously written up thoughts on where ES6 modules fall short that are worth noting. Try them out yourself using some of the options below and see what you think.

Use it today

Object.observe()

The idea behind Object.observe

is that we gain the ability to observe and notify applications of

changes made to specific JavaScript objects. Such changes include

properties being added, updated, removed or reconfigured.

Property observing is behaviour we commonly find in JavaScript MVC frameworks at at the moment and is an important component of data-binding, found in solutions like AngularJS and Ember.

This is a fundamentally important addition to JS as it could both offer performance improvements over a framework's custom implementations and allow easier observation of plain native objects.

- // A model can be a simple object

- var todoModel = {

- label: 'Default',

- completed: false

- };

- // Which we then observe

- Object.observe(todoModel, function(changes) {

- changes.forEach(function(change, i) {

- console.log(change);

- /*

- What property changed? change.name

- How did it change? change.type

- Whats the current value? change.object[change.name]

- */

- });

- });

- // Examples

- todoModel.label = 'Buy some more milk';

- /*

- label changed

- It was changed by being updated

- Its current value is 'Buy some more milk'

- */

- todoModel.completeBy = '01/01/2013';

- /*

- completeBy changed

- It was changed by being new

- Its current value is '01/01/2013'

- */

- delete todoModel.completed;

- /*

- completed changed

- It was changed by being deleted

- Its current value is undefined

- */

Availability: Object.observe will be available in Chrome Canary behind the "Enable Experimental JS APIs" flag. If you don't feel like getting that setup, you can also checkout this video by Rafael Weinstein discussing the proposal.

Use it today

- Special build of Chromium

- Watch.JS appears to offer similar behaviour, but isn't a polyfill or shim for

Object.observeoutright

Default Parameter Values

Default

parameter values allow us to initialize parameters if they are not

explicitly supplied. This means that we no longer have to write options = options || {};.

The syntax is modified by allowing an (optional) initialiser after the parameter names:

- function addTodo(caption = 'Do something') {

- console.log(caption);

- }

- addTodo(); // Do something

Only trailing parameters may have default values:

- function addTodo(caption, order = 4) {}

- function addTodo(caption = 'Do something', order = 4) {}

- function addTodo(caption, order = 10, other = this) {}

Availability: FF18

Block Scoping

Block scoping introduces new declaration forms for defining variables scoped to a single block. This includes:

let: which syntactically is quite similar tovar, but defines a variable in the current block function, allowing function declarations in nested blocksconst: likelet, but is for read-only constant declarations

Using let in place of var

makes it easier to define block-local variables without worrying about

them clashing with variables elsewhere in the same function body. The

scope of a variable that's been declared inside a let statement using var is the same as if it had been declared outside the let statement. These types of variables will still have function scoping.

- var x = 8;

- var y = 0;

- let (x = x+10, y = 12) {

- console.log(x+y); // 30

- }

- console.log(x + y); // 8

let availability: FF18, Chrome 24+

const availability: FF18, Chrome 24+, SF6, WebKit, Opera 12

Maps and sets

Maps

Many of you will already be familiar with the concept of maps as we've been using plain JavaScript objects as them for quite some time. Maps allow us to map a value to a unique key such that we can retrieve the value using the key without the pains of prototype-based inheritance.

With the Maps set() method, new name-value pairs are stored in the map and using get(), the values can be retrieved. Maps also have the following three methods:

has(key): a boolean check to test if a key existsdelete(key): deletes the key specified from the mapsize(): returns the number of stored name-value pairs

- let m = new Map();

- m.set('todo', 'todo'.length); // "something" → 4

- m.get('todo'); // 4

- m.has('todo'); // true

- m.delete('todo'); // true

- m.has('todo'); // false

Availability: FF18

Use it today

Sets

As Nicholas has pointed out before, sets won't be new to developers coming from Ruby or Python, but it's a feature thats been missing from JavaScript. Data of any type can be stored in a set, although values can be set only once. They are an effective means of creating ordered list of values that cannot contain duplicates.

add(value)– adds the value to the set.delete(value)– sets the value for the key in the set.has(value)– returns a boolean asserting whether the value has been added to the set

- let s = new Set([1, 2, 3]); // s has 1, 2 and 3.

- s.has(-Infinity); // false

- s.add(-Infinity); // s has 1, 2, 3, and -Infinity.

- s.has(-Infinity); // true

- s.delete(-Infinity); // true

- s.has(-Infinity); // false

One possible use for sets is reducing the complexity of filtering operations. e.g:

- function unique(array) {

- var seen = new Set;

- return array.filter(function (item) {

- if (!seen.has(item)) {

- seen.add(item);

- return true;

- }

- });

- }

This results in O(n) for filtering uniques in an array. Almost all methods of array unique with objects are O(n^2) (credit goes to Brandon Benvie for this suggestion).

Availability: Firefox 18, Chrome 24+

Use it today

Proxies

The Proxy API will allow us to create objects whose properties may be computed at run-time dynamically. It will also support hooking into other objects for tasks such as logging or auditing.

- var obj = {foo: "bar"};

- var proxyObj = Proxy.create({

- get: function(obj, propertyName) {

- return 'Hey, '+ propertyName;

- }

- });

- console.log(proxyObj.Alex); // "Hey, Alex"

Also checkout Zakas' Stack implementation using ES6 proxies experiment.

Availability: FF18, Chrome 24

WeakMaps

WeakMaps help developers avoid memory leaks by holding references to their properties weakly, meaning that if a WeakMap is the only object with a reference to another object, the garbage collector may collect the referenced object. This behavior differs from all variable references in ES5.

A key property of Weak Maps is the inability to enumerate their keys.

- let m = new WeakMap();

- m.set('todo', 'todo'.length); // Exception!

- // TypeError: Invalid value used as weak map key

- m.has('todo'); // Exception!

- // TypeError: Invalid value used as weak map key

- let wmk = {};

- m.set(wmk, 'thinger'); // wmk → 'thinger'

- m.get(wmk); // 'thinger'

- m.has(wmk); // true

- m.delete(wmk); // true

- m.has(wmk); // false

So again, the main difference between WeakMaps and Maps is that WeakMaps are not enumerable.

Use it today

API improvements

Object.is

Introduces a function for comparison called Object.is. The main difference between === and Object.is are the way NaNs and (negative) zeroes are treated. A NaN is equal to another NaN and negative zeroes are not equal from other positive zeroes.

- Object.is(0, -0); // false

- Object.is(NaN, NaN); // true

- 0 === -0; // true

- NaN === NaN; // false

Availability: Chrome 24+

Use it today

Array.from

Array.from:

Converts a single argument that is an array-like object or list (eg.

arguments, NodeList, DOMTokenList (used by classList), NamedNodeMap

(used by attributes property)) into a new Array() and returns it;

Converting any Array-Like objects:

- Array.from({

- 0: 'Buy some milk',

- 1: 'Go running',

- 2: 'Pick up birthday gifts',

- length: 3

- });

The following examples illustrate common DOM use cases:

- var divs = document.querySelectorAll('div');

- Array.from(divs);

- // [<div class="some classes" data-info="12"></div>, <div data-info="10"></div>]

- Array.from(divs).forEach(function(node) {

- console.log(node);

- });

Use it today

Conclusions

ES.next is shaping up to potentially include solutions for what many of us consider are missing from JavaScript at the moment. Whilst ES6 is targeting a 2013 spec release, browsers are already implementing individual features and it's only a matter of time before their availability is widespread.

In the meantime, we can use (some) modern browsers, transpilers, shims and in some cases custom builds to experiment with features before ES6 is fully here.

For more examples and up to date information, feel free to checkout the TC39 Codex Wiki (which was a great reference when putting together this post) maintained by Dave Herman and others. It contains summaries of all features currently being targeted for the next version of JavaScript.

Exciting times are most definitely ahead.

Thursday, November 08. 2012

TouchDevelop Now Available as Web App

Via Technet

-----

If you’re a software developer—or if you follow the work of software developers—you’ve probably heard of TouchDevelop,

a Microsoft Research app that enables you to write code for your phone

using scripts on your phone. Its ability to bring the excitement of

programming to Windows Phone 7 has reaped lots of enthusiasm from the

development community over the past year or so.

Now, the team behind TouchDevelop has taken things a step further, with a web app that can work on any Windows 8

device with a touchscreen. You can write Windows Store apps simply by

tapping on the screen of your device. The web app also works with a

keyboard and mouse, but the touchscreen capability means that the

keyboard is not required. To learn more, watch this video.

This reimplementation of TouchDevelop went live just in time for Build,

Microsoft’s annual conference that helps developers learn how to take

advantage of Windows 8. The conference is being held Oct. 30-Nov. 2 in

Redmond, Wash.

“Just as users could turn their scripts into Windows Phone apps,” says Nikolai Tillmann, principal research software-design engineer with the Research in Software Engineering (RiSE) team at Microsoft Research Redmond, “we will also allow our users to turn their scripts into Windows Store apps.”

The TouchDevelop web app, which requires Internet Explorer 10,

enables developers to publish their scripts so they can be shared with

others using TouchDevelop. As with the Windows Phone version, a

touchdevelop.com cloud service enables scripts to be published and

queried, and when you log in with the same credentials, all of your

scripts are synchronized between all your platforms and devices.

While

in the TouchDevelop web app, users can navigate to the properties of an

installed script already created. Videos describing editor operation of

the TouchDevelop web app are available on the project’s webpage.

TouchDevelop shipped as a Windows Phone app about a year and a half ago and has seen strong downloads and reviews in the Windows Phone Store.

“Our

TouchDevelop app for Windows Phone has been downloaded more than

200,000 times,” Tillmann says, “and more than 20,000 users have logged

in with a Windows Live ID or via Facebook.”

Since

the app became available, Tillmann and his RiSE colleagues have been

astounded by the creativity the user base has demonstrated. Further

Windows 8 developer excitement will be on display during Build, which is being streamed to audiences worldwide.

Wednesday, June 20. 2012

ArduSat: a real satellite mission that you can be a part of

Via DVICE

-----

We've been writing a lot recently about how the private space industry is poised to make space cheaper and more accessible. But in general, this is for outfits such as NASA, not people like you and me.

Today, a company called NanoSatisfi is launching a Kickstarter project to send an Arduino-powered satellite into space, and you can send an experiment along with it.

Whether it's private industry or NASA or the ESA or anyone else, sending stuff into space is expensive. It also tends to take approximately forever to go from having an idea to getting funding to designing the hardware to building it to actually launching something. NanoSatisfi, a tech startup based out of NASA's Ames Research Center here in Silicon Valley, is trying to change all of that (all of it) by designing a satellite made almost entirely of off-the-shelf (or slightly modified) hobby-grade hardware, launching it quickly, and then using Kickstarter to give you a way to get directly involved.

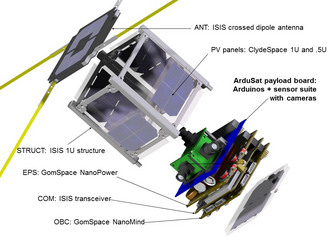

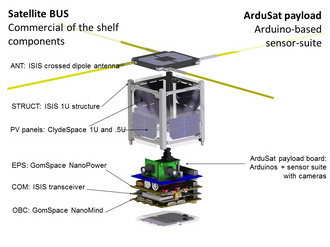

ArduSat is based on the CubeSat platform, a standardized satellite framework that measures about four inches on a side and weighs under three pounds. It's just about as small and cheap as you can get when it comes to launching something into orbit, and while it seems like a very small package, NanoSatisfi is going to cram as much science into that little cube as it possibly can.

Here's the plan: ArduSat, as its name implies, will run on Arduino boards, which are open-source microcontrollers that have become wildly popular with hobbyists. They're inexpensive, reliable, and packed with features. ArduSat will be packing between five and ten individual Arduino boards, but more on that later. Along with the boards, there will be sensors. Lots of sensors, probably 25 (or more), all compatible with the Arduinos and all very tiny and inexpensive. Here's a sampling:

Yeah, so that's a lot of potential for science, but the entire Arduino sensor suite is only going to cost about $1,500. The rest of the satellite (the power system, control system, communications system, solar panels, antennae, etc.) will run about $50,000, with the launch itself costing about $35,000. This is where you come in.

NanoSatisfi is looking for Kickstarter funding to pay for just the launch of the satellite itself: the funding goal is $35,000. Thanks to some outside investment, it's able to cover the rest of the cost itself. And in return for your help, NanoSatisfi is offering you a chance to use ArduSat for your own experiments in space, which has to be one of the coolest Kickstarter rewards ever.

- For a $150 pledge, you can reserve 15 imaging slots on ArduSat. You'll be able to go to a website, see the path that the satellite will be taking over the ground, and then select the targets you want to image. Those commands will be uploaded to the ArduSat, and when it's in the right spot in its orbit, it'll point its camera down at Earth and take a picture which will be then emailed right to you. From space.

- For $300, you can upload your own personal message to ArduSat, where it will be broadcast back to Earth from space for an entire day. ArduSat is in a polar orbit, so over the course of that day, it'll circle the Earth seven times and your message will be broadcast over the entire globe.

- For $500, you can take advantage of the whole point of ArduSat and run your very own experiment for an entire week on a selection of ArduSat's sensors. You know, in space. Just to be clear, it's not like you're just having your experiment run on data that's coming back to Earth from the satellite. Rather, your experiment is uploaded to the satellite itself, and it's actually running on one of the Arduino boards on ArduSat real time, which is why there are so many identical boards packed in there.

Now, NanoSatisfi itself doesn't really expect to get involved with a lot of the actual experiments that the ArduSat does: rather, it's saying "here's this hardware platform we've got up in space, it's got all these sensors, go do cool stuff." And if the stuff that you can do with the existing sensor package isn't cool enough for you, backers of the project will be able to suggest new sensors and new configurations, even for the very first generation ArduSat.

To make sure you don't brick the satellite with buggy code, NanSatisfi will have a duplicate satellite in a space-like environment here on Earth that it'll use to test out your experiment first. If everything checks out, your code gets uploaded to the satellite, runs in whatever timeslot you've picked, and then the results get sent back to you after your experiment is completed. Basically, you're renting time and hardware on this satellite up in space, and you can do (almost) whatever you want with that.

ArduSat has a lifetime of anywhere from six months to two years. None of this payload stuff (neither the sensors nor the Arduinos) are specifically space-rated or radiation-hardened or anything like that, and some of them will be exposed directly to space. There will be some backups and redundancy, but partly, this will be a learning experience to see what works and what doesn't. The next generation of ArduSat will take all of this knowledge and put it to good use making a more capable and more reliable satellite.

This, really, is part of the appeal of ArduSat: with a fast,

efficient, and (relatively) inexpensive crowd-sourced model, there's a

huge potential for improvement and growth. For example, If this

Kickstarter goes bananas and NanoSatisfi runs out of room for people to

get involved on ArduSat, no problem, it can just build and launch

another ArduSat along with the first, jammed full of (say) fifty more

Arduinos so that fifty more experiments can be run at the same time. Or

it can launch five more ArduSats. Or ten more. From the decision to

start developing a new ArduSat to the actual launch of that ArduSat is a

period of just a few months. If enough of them get up there at the same

time, there's potential for networking multiple ArduSats together up in

space and even creating a cheap and accessible global satellite array.

If this sounds like a lot of space junk in the making, don't worry: the

ArduSats are set up in orbits that degrade after a year or two, at which

point they'll harmlessly burn up in the atmosphere. And you can totally

rent the time slot corresponding with this occurrence and measure

exactly what happens to the poor little satellite as it fries itself to a

crisp.

Longer term, there's also potential for making larger ArduSats with more complex and specialized instrumentation. Take ArduSat's camera: being a little tiny satellite, it only has a little tiny camera, meaning that you won't get much more detail than a few kilometers per pixel. In the future, though, NanoSatisfi hopes to boost that to 50 meters (or better) per pixel using a double or triple-sized satellite that it'll call OptiSat. OptiSat will just have a giant camera or two, and in addition to taking high resolution pictures of Earth, it'll also be able to be turned around to take pictures of other stuff out in space. It's not going to be the next Hubble, but remember, it'll be under your control.

NanoSatisfi's Peter Platzer holds a prototype ArduSat board,

including the master controller, sensor suite, and camera. Photo: Evan

Ackerman/DVICE

Assuming the Kickstarter campaign goes well, NanoSatisfi hopes to complete construction and integration of ArduSat by about the end of the year, and launch it during the first half of 2013. If you don't manage to get in on the Kickstarter, don't worry- NanoSatisfi hopes that there will be many more ArduSats with many more opportunities for people to participate in the idea. Having said that, you should totally get involved right now: there's no cheaper or better way to start doing a little bit of space exploration of your very own.

Check out the ArduSat Kickstarter video below, and head on through the link to reserve your spot on the satellite.

-----

Wednesday, April 18. 2012

The Semicolon Wars

Via Christian Babski

-----

Here(@American Scientist) is an interesting and rather complete article on programming language [evolution,war] with some infographics on programming history and methods. It is not that technical, making the reading accessible to any one.

Tuesday, April 17. 2012

HTML5: A blessing or a curse?

Via develop

-----

Develop looks at the platform with ambitions to challenge Adobe's ubiquitous Flash web player

Initially heralded as the future of browser gaming and the next step beyond the monopolised world of Flash, HTML5 has since faced criticism for being tough to code with and possessing a string of broken features.

The coding platform, the fifth iteration of the HTML standard, was supposed to be a one stop shop for developers looking to create and distribute their game to a multitude of platforms and browsers, but things haven’t been plain sailing.

Not just including the new HTML mark-up language, but also incorporating other features and APIs such as CSS3, SVG and JavaScript, the platform was supposed to allow for the easy insertion of features for the modern browser such as video and audio, and provide them without the need for users to install numerous plug-ins.

And whilst this has worked to a certain degree, and a number of companies such as Microsoft, Apple, Google and Mozilla under the W3C have collaborated to bring together a single open standard, the problems it possesses cannot be ignored.

Thursday, April 05. 2012

MIT Project Aims to Deliver Printable, Mass-Market Robots

Via Wired

-----

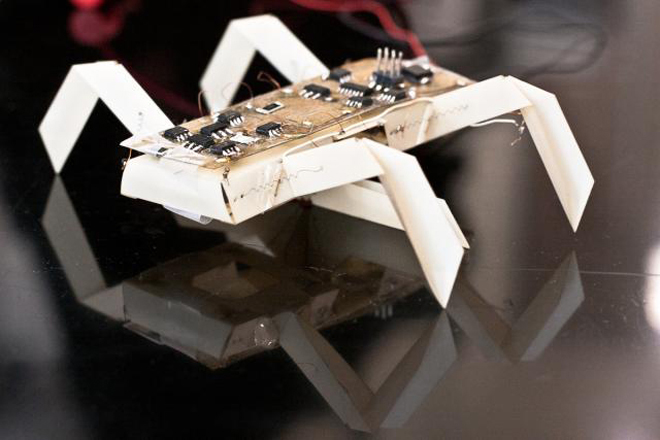

Insect printable robot. Photo: Jason Dorfman, CSAIL/MIT

Printers can make mugs, chocolate and even blood vessels. Now, MIT scientists want to add robo-assistants to the list of printable goodies.

Today, MIT announced a new project, “An Expedition in Computing Printable Programmable Machines,” that aims to give everyone a chance to have his or her own robot.

Need help peering into that unreasonably hard-to-reach cabinet, or wiping down your grimy 15th-story windows? Walk on over to robo-Kinko’s to print, and within 24 hours you could have a fully programmed working origami bot doing your dirty work.

“No system exists today that will take, as specification, your functional needs and will produce a machine capable of fulfilling that need,” MIT robotics engineer and project manager Daniela Rus said.

Unfortunately, the very earliest you’d be able to get your hands on an almost-instant robot might be 2017. The MIT scientists, along with collaborators at Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania, received a $10 million grant from the National Science Foundation for the 5-year project. Right now, it’s at very early stages of development.

So far, the team has prototyped two mechanical helpers: an

insect-like robot and a gripper. The 6-legged tick-like printable robot

could be used to check your basement for gas leaks or to play with your

cat, Rus says. And the gripper claw, which picks up objects, might be

helpful in manufacturing, or for people with disabilities, she says.

The two prototypes cost about $100 and took about 70 minutes to build. The real cost to customers will depend on the robot’s specifications, its capabilities and the types of parts that are required for it to work.

The researchers want to create a one-size-fits-most platform to circumvent the high costs and special hardware and software often associated with robots. If their project works out, you could go to a local robo-printer, pick a design from a catalog and customize a robot according to your needs. Perhaps down the line you could even order-in your designer bot through an app.

Their approach to machine building could “democratize access to robots,” Rus said. She envisions producing devices that could detect toxic chemicals, aid science education in schools, and help around the house.

Although bringing robots to the masses sounds like a great idea (a sniffing bot to find lost socks would come in handy), there are still several potential roadblocks to consider — for example, how users, especially novice ones, will interact with the printable robots.

“Maybe this novice user will issue a command that will break the device, and we would like to develop programming environments that have the capability of catching these bad commands,” Rus said.

As it stands now, a robot would come pre-programmed to perform a set of tasks, but if a user wanted more advanced actions, he or she could build up those actions using the bot’s basic capabilities. That advanced set of commands could be programmed in a computer and beamed wirelessly to the robot. And as voice parsing systems get better, Rus thinks you might be able to simply tell your robot to do your bidding.

Durability is another issue. Would these robots be single-use only? If so, trekking to robo-Kinko’s every time you needed a bot to look behind the fridge might get old. These are all considerations the scientists will be grappling with in the lab. They’ll have at least five years to tease out some solutions.

In the meantime, it’s worth noting that other other groups are also building robots using printers. German engineers printed a white robotic spider last year. The arachnoid carried a camera and equipment to assess chemical spills.

And at Drexel University, paleontologist Kenneth Lacovara and mechanical engineer James Tangorra are trying to create a robotic dinosaur from dino-bone replicas. The 3-D-printed bones are scaled versions of laser-scanned fossils. By the end of 2012, Lacovara and Tangorra hope to have a fully mobile robotic dinosaur, which they want to use to study how dinosaurs, like large sauropods, moved.

Lancovara thinks the MIT project is an exciting and promising one: “If it’s a plug-and-play system, then it’s feasible,” he said. But “obviously, it [also] depends on the complexity of the robot.” He’s seen complex machines with working gears printed in one piece, he says.

Right now, the MIT researchers are developing an API that would facilitate custom robot design and writing algorithms for the assembly process and operations.

If their project works out, we could all have a bot to call our own in a few years. Who said print was dead?

Friday, March 30. 2012

Fake ID holders beware: facial recognition service Face.com can now detect your age

Via VB

-----

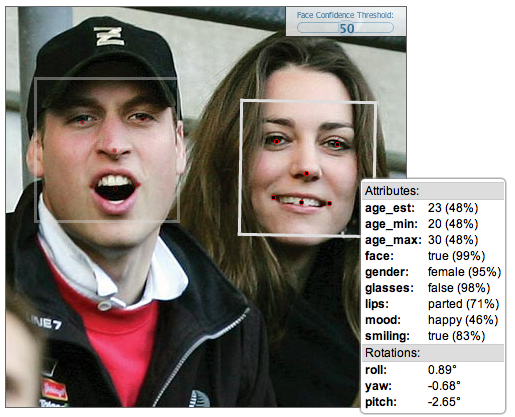

Facial-recognition platform Face.com could foil the plans of all those under-age kids looking to score some booze. Fake IDs might not fool anyone for much longer, because Face.com claims its new application programming interface (API) can be used to detect a person’s age by scanning a photo.

With its facial recognition system, Face.com has built two Facebook apps that can scan photos and tag them for you. The company also offers an API for developers to use its facial recognition technology in the apps they build.

Its latest update to the API can scan a photo and supposedly determine a person’s minimum age, maximum age, and estimated age. It might not be spot-on accurate, but it could get close enough to determine your age group.

“Instead of trying to define what makes a person young or old, we provide our algorithms with a ton of data and the system can reverse engineer what makes someone young or old,” Face.com chief executive Gil Hirsch told VentureBeat in an interview. ”We use the general structure of a face to determine age. As humans, our features are either heighten or soften depending on the age. Kids have round, soft faces and as we age, we have elongated faces.”

The algorithms also take wrinkles, facial smoothness, and other telling age signs into account to place each scanned face into a general age group. The accuracy, Hirsch told me, is determined by how old a person looks, not necessarily how old they actually are. The API also provides a confidence level on how well it could determine the age, based on image quality and how the person looks in photo, i.e. if they are turned to one side or are making a strange face.

“Adults are much harder to figure out [their age], especially celebrities. On average, humans are much better at detecting ages than machines,” said Hirsch.

The hope is to build the technology into apps that restrict or tailor content based on age. For example the API could be built into a Netflix app, scan a child’s face when they open the app, determine they’re too young to watch The Hangover, and block it. Or — and this is where the tech could get futuristic and creepy — a display with a camera could scan someone’s face when they walk into a store and deliver ads based on their age.

In addition to the age-detection feature, Face.com says it has updated its API with 30 percent better facial recognition accuracy and new recognition algorithms. The updates were announced Thursday and the API is available for any developer to use.

One developer has already used the API to build app called Age Meter, which is available in the Apple App Store. On its iTunes page, the entertainment-purposes-only app shows pictures of Justin Bieber and Barack Obama with approximate ages above their photos.

Other companies in this space include Cognitec, with its FaceVACS software development kit, and Bayometric, which offers FaceIt Face Recognition. Google has also developed facial-recognition technology for Android 4.0 and Apple applied for a facial recognition patent last year.

The technology behind scanning someone’s picture, or even their face, to figure out their age still needs to be developed for complete accuracy. But, the day when bouncers and liquor store cashiers can use an app to scan a fake ID’s holder’s face, determine that they are younger than the legal drinking age, and refuse to sell them wine coolers may not be too far off.

Friday, March 23. 2012

Android and Linux re-merge into one operating system

Via ZDNet

-----

Android has always been Linux, but for years the Android project went its own way and its code wasn’t merged back into the main Linux tree. Now, much sooner than Linus Torvalds, Linux’s founder and lead developer, had expected, Android has officially merged back into Linux’s mainline.

The fork between Android and Linux all began in the fall of 2010, “Google engineer Patrick Brady stated that Android is not Linux” That was never actually the case.Android has always been Linux at heart.

At the same time though Google did take Android in a direction that wasn’t compatible with the mainstream Linux kernel. As Greg Kroah-Hartman, the maintainer of the stable Linux kernel for the Linux Foundation and head of the Linux Driver Project, wrote in Android and the Linux kernel community, “The Android kernel code is more than just the few weird drivers that were in the drivers/staging/androidsubdirectory in the kernel. In order to get a working Android system, you need the new lock type they have created, as well as hooks in the core system for their security model. In order to write a driver for hardware to work on Android, you need to properly integrate into this new lock, as well as sometimes the bizarre security model. Oh, and then there’s the totally-different framebuffer driver infrastructure as well.” That flew like a lead balloon in Android circles.

This disagreement sprang from several sources. One was that Google’s Android developers had adopted their own way to address power issues with WakeLocks. The other cause, as Google open source engineering manager Chris DiBona pointed out, was that Android’s programmers were so busy working on Android device specifics that they had done a poor job of co-coordinating with the Linux kernel developers.

The upshot was that developer circles have had many heated words over what’s the right way of handling Android specific code in Linux. The upshot of the dispute was that Torvalds dropped the Android drivers from the main Linux kernel in late 2009.

Despite these disagreements, there was never any danger as one claim had it in March 2011, that Android was somehow in danger of being sued by Linux because of Gnu General Public License, version 2 (GPLv2) violations. As Linus himself said at the time, claims that the Android violated the GPL were “totally bogus. We’ve always made it very clear that the kernel system call interfaces do not in any way result in a derived work as per the GPL, and the kernel details are exported through the kernel headers to all the normal glibc interfaces too.”

Over the last few months though, as Torvalds explained last fall, that while “there’s still a lot of merger to be done … eventually Android and Linux would come back to a common kernel, but it will probably not be for four to five years.” Kroah-Hartman added at the time that one problem is that “Google’s Android team is very small and over-subscribed to so they’re resource restrained It would be cheaper in the long run for them to work with us.” Torvalds then added that “We’re just going different directions for a while, but in the long run the sides will come together so I’m not worried.”

In the event the re-merger of the two went much faster than expected. At the 2011 Kernel Summit in Prague in late October, the Linux kernel developers “agreed that the bulk of theAndroid kernel code should probably be merged into the mainline.” To help this process along, theAndroid Mainlining Project was formed.

Things continued to go along much faster then anyone had foreseen. By December, Kroah-Hartman could write, “by the 3.3 kernel release, the majority of the Android code will be merged, but more work is still left to do to better integrate the kernel and userspace portions in ways that are more palatable to the rest of the kernel community. That will take longer, but I don’t foresee any major issues involved.” He was right.

Today, you can compile the Android code in Linux 3.3 and it will boot. Still, as Kroah-Hartman warned, WakeLocks, still aren’t in the main kernel, but even that’s getting worked on. For all essential purposes, Android and Linux are back together again.

Related Stories:

Linus Torvalds on Android, the Linux fork

It’s time Google starts paying for Android updates

Google open source guru says Android code will be in Linux kernel in time

Tuesday, March 13. 2012

Research in Programming Languages

Via Tagide

By Crista Videira Lopes

-----

Is there still research to be done in Programming Languages? This essay touches both on the topic of programming languages and on the nature of research work. I am mostly concerned in analyzing this question in the context of Academia, i.e. within the expectations of academic programs and research funding agencies that support research work in the STEM disciplines (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). This is not the only possible perspective, but it is the one I am taking here.

PLs are dear to my heart, and a considerable chunk of my career was made in that area. As a designer, there is something fundamentally interesting in designing a language of any kind. It’s even more interesting and gratifying when people actually start exercising those languages to create non-trivial software systems. As a user, I love to use programming languages that I haven’t used before, even when the languages in question make me curse every other line.

But the truth of the matter is that ever since I finished my Ph.D. in the late 90s, and especially since I joined the ranks of Academia, I have been having a hard time convincing myself that research in PLs is a worthy endeavor. I feel really bad about my rational arguments against it, though. Hence this essay. Perhaps by the time I am done with it I will have come to terms with this dilemma.

Back in the 50s, 60s and 70s, programming languages were a BigDeal, with large investments, upfront planning, and big drama on standardization committees (Ada was the epitome of that model). Things have changed dramatically during the 80s. Since the 90s, a considerable percentage of new languages that ended up being very popular were designed by lone programmers, some of them kids with no research inclination, some as a side hobby, and without any grand goal other than either making some routine activities easier or for plain hacking fun. Examples:

- PHP, by Rasmus Lerdorf circa 1994, “originally used for tracking visits to his online resume, he named the suite of scripts ‘Personal Home Page Tools,’ more frequently referenced as ‘PHP Tools.’ ” [1] PHP is a marvel of how a horrible language can become the foundation of large numbers of applications… for a second time! Worse is Better redux. According one informal but interesting survey, PHP is now the 4th most popular programming language out there, losing only to C, Java and C++.

- JavaScript, by Brendan Eich circa 1995, “Plus, I had to be done in ten days or something worse than JS would have happened.” [2] According to that same survey, JavaScript is the 5th most popular language, and I suspect it is climbing up that rank really fast. It may be #1 by now.

- Python, by Guido van Rossum circa 1990, “I was looking for a ‘hobby’ programming project that would keep me occupied during the week around Christmas.” [3] Python comes at #6, and its strong adoption by scientific computing communities is well know.

- Ruby, by Yukihiro “Matz” Matsumoto circa 1994, “I wanted a scripting language that was more powerful than Perl, and more object-oriented than Python. That’s why I decided to design my own language.” [4] At #10 in that survey.

Compare this mindset with the context in which the the older well-known programming languages emerged:

- Fortran, 50s, originally developed by IBM as part of their core business in computing machines.

- Cobol, late 50s, designed by a large committee from the onset, sponsored by the DoD.

- Lisp, late 50s, main project occupying 2 professors at MIT and their students, with the grand goal of producing an algebraic list processing language for artificial intelligence work, also funded by the DoD.

- C, early 70s, part of the large investment that Bell Labs was doing in the development of Unix.

- Smalltalk, early 70s, part of a large investment that Xerox did in “inventing the future” of computers.

Back then, developing a language processor was, indeed, a very big deal. Computers were slow, didn’t have a lot of memory, the language processors had to be written in low-level assembly languages… it wasn’t something someone would do in their rooms as a hobby, to put it mildly. Since the 90s, however, with the emergence of PCs and of decent low-level languages like C, developing a language processor is no longer a BigDeal. Hence, languages like PHP and JavaScript.

There is a lot of fun in designing new languages, but this fun is not an exclusive right of researchers with, or working towards, Ph.Ds. Given all the knowledge about programming languages these days, anyone can do it. And many do. And here’s the first itchy point: there appears to be no correlation between the success of a programming language and its emergence in the form of someone’s doctoral or post-doctoral work. This bothers me a lot, as an academic. It appears that deep thoughts, consistency, rigor and all other things we value as scientists aren’t that important for mass adoption of programming languages. But then again, I’m not the first to say it. It’s just that this phenomenon is hard to digest, and if you really grasp it, it has tremendous consequences. If people (the potential users) don’t care about conceptual consistency, why do we keep on trying to achieve that?

To be fair, some of those languages designed in the 90s as side projects, as they became important, eventually became more rigorous and consistent, and attracted a fair amount of academic attention and industry investment. For example, the Netscape JavaScript hacks quickly fell on Guy Steele’s lap resulting in the ECMAScript specification. Python was never a hack even if it started as a Christmas hobby. Ruby is a fun language and quite elegant from the beginning. PHP… well… it’s fun for possibly the wrong reasons. But the core of the matter is that “the right thing” was not the goal. It seems that a reliable implementation of a language that addresses an important practical need is the key for the popularity of a programming language. But being opportunistic isn’t what research is supposed to be about… (or is it?)

Also to be fair, not all languages designed in the 90s and later started as side projects. For example, Java was a relatively large investment by Sun Microsystems. So was .NET later by Microsoft.

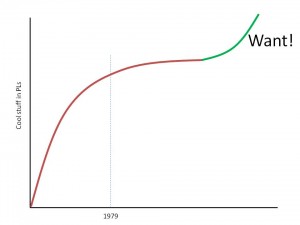

And, finally, all of these new languages, even when created over a week as someone’s pet project, sit on the shoulders of all things that existed before. This leads me to the second itch: one striking commonality in all modern programming languages, especially the popular ones, is how little innovation there is in them! Without exception, including the languages developed in research groups, they all feel like mashups of concepts that already existed in programming languages in 1979, wrapped up in their own idiosyncratic syntax. (I lied: exceptions go to aspects and monads both of which came in the 90s)

So

one pertinent question is: given that not much seems to have emerged

since 1979 (that’s 30+ years!), is there still anything to innovate in programming languages? Or have we reached the asymptotic plateau of innovation in this area?

So

one pertinent question is: given that not much seems to have emerged

since 1979 (that’s 30+ years!), is there still anything to innovate in programming languages? Or have we reached the asymptotic plateau of innovation in this area?

I need to make an important detour here on the nature of research.

<Begin Detour>

Perhaps I’m completely off; perhaps producing innovative new software is not a goal of [STEM] research. Under this approach, any software work is dismissed from STEM pursuits, unless it is necessary for some specific goal — like if you want to study some far-off galaxy and you need an IT infrastructure to collect the data and make simulations (S for Science); or if you need some glue code for piecing existing systems together (T for Technology); or if you need to improve the performance of something that already exists (E for Engineering); or if you are a working on some Mathematical model of computation and want to make your ideas come to life in the form of a language (M for Mathematics). This is an extreme submissive view of software systems, one that places software in the back sit of STEM and that denies the existence of value in research in/by software itself. If we want to lead something on our own, let’s just… do empirical studies of technology or become biologists/physicists/chemists/mathematicians or make existing things perform better or do theoretical/statistical models of universes that already exist or that are created by others. Right?

I confess I have a dysfunctional relationship with this idea. Personally, I can’t be happy without creating software things, but I have been able to make my scientist-self function both as a cold-minded analyst and, at times, as an expert passenger in someone else’s research project. The design work, for me, has moved to sabbatical time, evenings and weekends; I don’t publish it [much] other than the code itself and some informal descriptions. And yet, I loathe this situation.

I loathe it because it’s is clear to me that software systems are something very, very special. Software revolutionized everything in unexpected ways, including the methods and practices that our esteemed colleagues in the “hard” sciences hold near and dear for a very long time. The evolution of information technology in the past 60 years has been way off from what our colleagues thought they needed. Over and over again, software systems have been created that weren’t part of any scientific project, as such, and that ended up playing a central role in Science. Instead of trying to mimic our colleagues’ traditional practices, “computer scientists” ought to be showing the way to a new kind of science — maybe that new kind of science or that one or maybe something else. I dare to suggest that the something else is related to the design of things that have software in them. It should not be called Science. It is a bit like Engineering, but it’s not it either because we’re not dealing [just] with physical things. Technology doesn’t cut it either. It needs a new name, something that denotes “the design of things with software in them.” I will call it Design for short, even though that word is so abused that it has lost its meaning.

<Suspend Detour>

Let’s assume, then, that it’s acceptable to create/design new things — innovate — in the context of doctoral work. Now comes the real hard question.

If anyone — researchers, engineers, talented kids, summer interns — can design and implement programming languages, what are the actual hard goals that doctoral research work in programming languages seeks that distinguishes it from what anyone can do?

Let me attempt to answer these questions, first, with some well-known goals of language design:

- Performance — one can always have more of this; certain application domains need it more than others. This usually involves having to come up with interesting data structures and algorithms for the implementation of PLs that weren’t easy to devise.

- Human Productivity — one can always want more of this. There is no ending to trying to make development activities easier/faster.

- Verifiability — in some domains this is important.

There are other goals, but they are second-order. For example, languages may also need to catch up with innovations in hardware design — multi-core comes to mind. This is a second-order goal, the real goal behind it is to increase performance by taking advantage of potentially higher-performing hardware architectures.

In other words, someone wanting to do doctoral research work in programming languages ought to have one or more of these goals in mind, and — very important — ought to be ready to demonstrate how his/her ideas meet those goals. If you tell me that your language makes something run faster, consume less energy, makes some task easier or results in programs with less bugs, the scientist in me demands that you show me the data that supports such claims.

A lot of research activity in programming languages falls under the performance goal, the Engineering side of things. I think everyone in our field understands what this entails, and is able to differentiate good work from bad work under that goal. But a considerable amount of research activities in programming languages invoke the human productivity argument; entire sub-fields have emerged focusing on the engineering of languages that are believed to increase human productivity. So I’m going to focus on the human productivity goal. The human productivity argument touches on the core of what attracts most of us to creating things: having a direct positive effect on other people. It has been carelessly invoked since the beginning of Computer Science. (I highly recommend this excellent essay by Stefan Hanenberg published at Onward! 2010 with a critique of software science’s neglect of human factors)

Unfortunately, this argument is the hardest to defend. In fact, I am yet to see the first study that convincingly demonstrates that a programming language, or a certain feature of programming languages, makes software development a more productive process. If you know of such study, please point me to it. I have seen many observational studies and controlled experiments that try to do it [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, among many]. I think those studies are really important, there ought to be more of them, but they are always very difficult to do [well]. Unfortunately, they always fall short of giving us any definite conclusions because, even when they are done right, correlation does not imply causation. Hence the never-ending ping-pong between studies that focus on the same thing and seem to reach opposite conclusions, best known in the health sciences. We are starting to see that ping-pong in software science too, for example 7 vs 9. But at least these studies show some correlations, or lack thereof, given specific experimental conditions, and they open the healthy discussion about what conditions should be used in order to get meaningful results.

I have seen even more research and informal articles about programming languages that claim benefits to human productivity without providing any evidence for it whatsoever, other than the authors’ or the community’s intuition, at best based on rational deductions from abstract beliefs that have never been empirically verified. Here is one that surprised me because I have the highest respect for the academic soundness of Haskell. Statements like this “Haskell programs have fewer bugs because Haskell is: pure [...], strongly typed [...], high-level [...], memory managed [...], modular [...] [...] There just isn’t any room for bugs!” are nothing but wishful thinking. Without the data to support this claim, this statement is deceptive; while it can be made informally in a blog post designed to evangelize the crowd, it definitely should not be made in the context of doctoral work unless that work provides solid evidence for such a strong statement.

That article is not an outlier. The Internets are full of articles claiming improved software development productivity for just about every other language. No evidence is ever provided, the argumentation is always either (a) deducted from principles that are supposed to be true but that have never been verified, or (b) extrapolated from ad-hoc, highly biased, severely skewed personal experiences.

This is the main reason why I stopped doing research in Programming Languages in any official capacity. Back when I was one of the main evangelists for AOP I realized at some point that I had crossed the line to saying things for which I had very little evidence. I was simply… evangelizing, i.e. convincing others of an idea that I believed strongly. At some point I felt I needed empirical evidence for what I was saying. But providing evidence for the human productivity argument is damn hard! My scientist self cannot lead doctoral students into that trap, a trap that I know too well.

Moreover, designing and executing the experiments that lead to uncovering such evidence requires a lot of time and a whole other set of skills that have absolutely nothing to do with the time and skills for actually designing programming languages. We need to learn the methods that experimental psychologists use. And, in the end of all that work, we will be lucky if we unveil correlations but we will not be able to draw any definite conclusions, which is… depressing.

But without empirical evidence of any kind, and from a scientific perspective, unsubstantiated claims pertaining to, say, Haskell or AspectJ (which are mostly developed and used by academics and have been the topic of many PhD dissertations) are as good as unsubstantiated claims pertaining to, say, PHP (which is mostly developed and used by non-academics). The PHP community is actually very honest when it comes to stating the benefits of using the language. For example, here is an honest-to-god set of reasons for using PHP. Notice that there are no claims whatsoever about PHP leading to less bugs or higher programmer productivity (as if anyone would dare to state that!); they’re just pragmatic reasons. (Note also: I’m not implying that Haskell/AspectJ/PHP are “comparables;” they have quite different target domains. I’m just comparing the narratives surrounding those languages, the “stories” that the communities tell within themselves and to others)

OK, now that I made 823 enemies by pointing out that the claims about human productivity surrounding languages that have emerged in academic communities — and therefore ought to know better — are unsubstantiated, PLUS 865 enemies by saying that empirical user studies are inconclusive and depressing… let me try to turn my argument around.

Is the high bar of scientific evidence killing innovation in programming languages? Is this what’s causing the asymptotic behavior? It certainly is what’s keeping me away from that topic, but I’m just a grain of sand. What about the work of many who propose intriguing new design ideas that are then shot down in peer-review committees because of the lack of evidence?

This ties back to my detour on the nature of research.

<Join Detour> Design experimentation vs. Scientific evidence

So, we’re back to whether design innovation per se is an admissible first-order goal of doctoral work or not. And now that question is joined by a counterpart: is the provision of scientific evidence really required for doctoral work in programming languages?

If what we have in hand is not Science, we need to be careful not to blindly adopt methods that work well for Science, because that may kill the essence of our discipline. In my view, that essence has been the radical, fast-paced, off the mark design experimentation enabled by software. This rush is fairly incompatible with the need to provide scientific evidence for the design “hopes.”

I’ll try a parallel: drug design, the modern-day equivalent of alchemy. In terms of research it is similar to software: partly based on rigor, partly on intuitions, and now also on automated tools that simply perform an enormous amount of logical combinations of molecules and determine some objective function. When it comes to deployment, whoever is driving that work better put in place a plan for actually testing the theoretical expectations in the context of actual people. Does the drug really do what it is supposed to do without any harmful side effects? We require scientific evidence for the claimed value of experimental drugs. Should we require scientific evidence for the value of experimental software?

The parallel diverges significantly with respect to the consequences of failure. A failure in drug design experimentation may lead to people dying or getting even more sick. A failure in software design experimentation is only a big deal if the experiment had a huge investment from the beginning and/or pertains to safety-critical systems. There are still some projects like that, and for those, seeking solid evidence of their benefits before deploying the production version of the experiment is a good thing. But not all software systems are like that. Therefore the burden of scientific evidence may be too much to bear. It is also often the case that over time, the enormous amount of testing by real use is enough to provide assurances of all kinds.

One good example of design experimentation being at odds with scientific evidence is the proposal that Tim Berners-Lee made to CERN regarding the implementation of the hypertext system that became the Web. Nowhere in that proposal do we find a plan for verification of claims. That’s just a solid good proposal for an intriguing “linked information system.” I can imagine TB-L’s manager thinking: “hmm, ok, this is intriguing, he’s a smart guy, he’s not asking that many resources, let’s have him do it and see what comes of it. If nothing comes of it, no big deal.” Had TB-L have to devise a scientific or engineering assessment plan for that system beyond “in the second phase, we’ll install it on many machines” maybe the world would be very different today, because he might have gotten caught in the black hole of trying to find quantifiable evidence for something that didn’t need that kind of validation.

Granted, this was not a doctoral topic proposal; it was a proposal for the design and implementation of a very concrete system with software in it, one that (1) clearly identified the problem, (2) built on previous ideas, including the author’s own experience, (3) had some intriguing insights in it, (4) stated expected benefits and potential applications — down to the prediction of search engines and graph-based data analysis. Should a proposal like TB-L’s be rejected if it were to be a doctoral topic proposal? When is an unproven design idea doctoral material and other isn’t? If we are to accept design ideas without validation plans as doctoral material, how do we assess them?

Towards the discipline of Design

In order to do experimental design research AND be scientifically honest at the same time, one needs to let go of claims altogether. In that dreadful part of a topic proposal where the committee asks the student “what are your claims?” the student should probably answer “none of interest.” In experimental design research, one can have hopes or expectations about the effects of the system, and those must be clearly articulated, but very few certainties will likely come out of such type of work. And that’s ok! It’s very important to be honest. For example, it’s not ok to claim “my language produces bug-free programs” and then defend this with a deductive argument based on unproven assumptions; but it’s ok to state “I expect that my language produces programs with fewer bugs [but I don't have data to prove it].” TB-L’s proposal was really good at being honest.

Finally, here is an attempt at establishing a rigorous criteria for design assessment in the context of doctoral and post-doctoral research:

- Problem: how important and surprising is the problem and how good is its description? The problem space is, perhaps, the most important component for a piece of design research work. If the design is not well grounded in an interesting and important problem, then perhaps it’s not worth pursuing as research work. If it’s a old hard problem, it should be formulated in a surprising manner. Very often, the novelty of a design lies not in the design itself but in its designer seeing the problem differently. So — surprise me with the problem. Show me insights on the nature of the problem that we don’t already know.

- Potential: what intriguing possibilities are unveiled by the design? Good design research work should open up doors for new avenues of exploration.

- Feasibility: good design research work should be grounded on what is possible to do. The ideas should be demonstrated in the form of a working system.

- Additionally, design research work, like any other research work, needs to be placed in a solid context of what already exists.

This criteria has two consequences that I really like: first, it substantiates our intuitions about proposals such as TB-L’s “linked information system” being a fine piece of [design] research work; second, it substantiates our intuitions on the difference of languages like Haskell vs. languages like PHP. I leave that as an exercise to the reader!

Coming to terms

I would love to bring design back to my daytime activities. I would love to let my students engage in designing new things such as new programming languages and environments — I have lots of ideas for what I would like to do in that area! I believe there is a path to establishing a set of rigorous criteria regarding the assessment of design that is different from scientific/quantitative validation. All this, however, doesn’t depend on me alone. If my students’ papers are going to be shot down in program committees because of the lack of validation, then my wish is a curse for them. If my grant proposals are going to be rejected because they have no validation plan other than “and then we install it in many machines” or “and then we make the software open source and free of charge” then my wish is a curse for me. We need buy-in from a much larger community — in a way, reverse the trend of placing software research under the auspices of science and engineering [alone].