Sunday, October 06. 2013

Life in the fishbowl

Via aeon magazine

-----

In the future, most people will live in a total surveillance state – and some of us might even like it

A Banksy graffiti work in London. Photo by Cate Gillon/Getty Images

Suppose you’re walking home one night, alone, and you decide to take a shortcut through a dark alley. You make it halfway through, when suddenly you hear some drunks stumbling behind you. Some of them are shouting curses. They look large and powerful, and there are several of them. Nonetheless, you feel safe, because you know someone is watching.

You know this because you live in the future where surveillance is universal, ubiquitous and unavoidable. Governments and large corporations have spread cameras, microphones and other tracking devices all across the globe, and they also have the capacity to store and process oceans of surveillance data in real time. Big Brother not only watches your sex life, he analyses it. It sounds nightmarish — but it might be inevitable. So far, attempts to control surveillance have generally failed. We could be headed straight for the panopticon, and if recent news developments are any indication, it might not take that long to get there.

Maybe we should start preparing. And not just by wringing our hands or mounting attempts to defeat surveillance. For if there’s a chance that the panopticon is inevitable, we ought to do some hard thinking about its positive aspects. Cataloguing the downsides of mass surveillance is important, essential even. But we have a whole literature devoted to that. Instead, let’s explore its potential benefits.

The first, and most obvious, advantage of mass surveillance is a drastic reduction in crime. Indeed, this is the advantage most often put forward by surveillance proponents today. The evidence as to whether current surveillance achieves this is ambiguous; cameras, for instance, seem to have an effect on property crime, but not on incidences of violence. But today’s world is very different from a panopticon full of automatically analysed surveillance devices that leave few zones of darkness.

If calibrated properly, total surveillance might eradicate certain types of crime almost entirely. People respond well to inevitable consequences, especially those that follow swiftly on the heels of their conduct. Few would commit easily monitored crimes such as assault or breaking and entering, if it meant being handcuffed within minutes. This kind of ultra-efficient police capability would require not only sensors capable of recording crimes, but also advanced computer vision and recognition algorithms capable of detecting crimes quickly. There has been some recent progress on such algorithms, with further improvements expected. In theory, they would be able to alert the police in real time, while the crime was still ongoing. Prompt police responses would create near-perfect deterrence, and violent crime would be reduced to a few remaining incidents of overwhelming passion or extreme irrationality.

If surveillance recordings were stored for later analysis, other types of crimes could be eradicated as well, because perpetrators would fear later discovery and punishment. We could expect crimes such as low-level corruption to vanish, because bribes would become perilous (to demand or receive) for those who are constantly under watch. We would likely see a similar reduction in police brutality. There might be an initial spike in detected cases of police brutality under a total surveillance regime, as incidents that would previously have gone unnoticed came to light, but then, after a short while, the numbers would tumble. Ubiquitous video recording, mobile and otherwise, has already begun to expose such incidents.

On a smaller scale, mass surveillance would combat all kinds of abuses that currently go unreported because the abuser has power over the abused. You see this dynamic in a variety of scenarios, from the dramatic (child abuse) to the more mundane (line managers insisting on illegal, unpaid overtime). Even if the victim is too scared to report the crime, the simple fact that the recordings existed would go a long way towards equalising existing power differentials. There would be the constant risk of some auditor or analyst stumbling on the recording, and once the abused was out of the abuser’s control (grown up, in another job) they could retaliate and complain, proof in hand. The possibility of deferred vengeance would make abuse much less likely to occur in the first place.

With reduced crime, we could also expect a significant reduction in police work and, by extension, police numbers. Beyond a rapid-reaction force tasked with responding to rare crimes of passion, there would be no need to keep a large police force on hand. And there would also be no need for them to enjoy the special rights they do today. Police officers can, on mere suspicion, detain you, search your person, interrogate you, and sometimes enter your home. They can also arrest you on suspicion of vague ‘crimes’ such as ‘loitering with intent’. Our present police force is given these powers because it needs to be able to investigate. Police officers can’t be expected to know who committed what crime, and when, so they need extra powers to be able to figure this out, and still more special powers to protect themselves while they do so. But in a total-surveillance world, there would be no need for humans to have such extensive powers of investigation. For most crimes, guilt or innocence would be obvious and easy to establish from the recordings. The police’s role could be reduced to arresting specific individuals, who have violated specific laws.

If all goes well, there might be fewer laws for the police to enforce. Most countries currently have an excess of laws, criminalising all sorts of behaviour. This is only tolerated because of selective enforcement; the laws are enforced very rarely, or only against marginalised groups. But if everyone was suddenly subject to enforcement, there would have to be a mass legal repeal. When spliffs on private yachts are punished as severely as spliffs in the ghetto, you can expect the marijuana legalisation movement to gather steam. When it becomes glaringly obvious that most people simply can’t follow all the rules they’re supposed to, these rules will have to be reformed. In the end, there is a chance that mass surveillance could result in more personal freedom, not less.

The military is another arm of state power that is ripe for a surveillance-inspired shrinking. If cross-border surveillance becomes ubiquitous and effective, we could see a reduction in the $1.7 trillion that the world spends on the military each year. Previous attempts to reduce armaments have ultimately been stymied by a lack of reliable verification. Countries can never trust that their enemies aren’t cheating, and that encourages them to cheat themselves. Arms races are also made worse by a psychological phenomenon, whereby each side interprets the actions of the other as a dangerous provocation, while interpreting its own as purely defensive or reactive. With cross-border mass surveillance, countries could check that others are abiding by the rules, and that they weren’t covertly preparing for an attack. If intelligence agencies were to use all the new data to become more sophisticated observers, countries might develop a better understanding of each other. Not in the hand-holding, peace-and-love sense, but in knowing what is a genuine threat and what is bluster or posturing. Freed from fear of surprising new weapons, and surprise attacks, countries could safely shrink their militaries. And with reduced armies, we should be able to expect reduced warfare, continuing the historical trend in conflict reduction since the end of the Second World War.

Of course, these considerations pale when compared with the potential for mass surveillance to help prevent global catastrophic risks, and other huge disasters. Pandemics, to name just one example, are among the deadliest dangers facing the human race. The Black Death killed a third of Europe’s population in the 14th century and, in the early 20th century, the Spanish Flu killed off between 50 and 100 million people. In addition, smallpox buried more people than the two world wars combined. There is no reason to think that great pandemics are a thing of the past, and in fact there are reasons to think that another plague could be due soon. There is also the possibility that a pandemic could arise from synthetic biology, the human manipulation of microbes to perform specific tasks. Experts are divided as to the risks involved in this new technology, but they could be tremendous, especially if someone were to release, accidentally or malevolently, infectious agents deliberately engineered for high transmissibility and deadliness.

You can imagine how many lives would have been saved had AIDS been sniffed out by epidemiologists more swiftly

Mass surveillance could help greatly here, by catching lethal pandemics in their earliest stages, or beforehand, if we were to see one being created artificially. It could also expose lax safety standards or dangerous practices in legitimate organisations. Surveillance could allow for quicker quarantines, and more effective treatment of pandemics. Medicines and doctors could be rushed to exactly the right places, and micro-quarantines could be instituted. More dramatic measures, such as airport closures, are hard to implement on a large scale, but these quick-response tactics could be implemented narrowly and selectively. Most importantly, those infected could be rapidly informed of their condition, allowing them to seek prompt treatment.

With proper procedures and perfect surveillance, we could avoid pandemics altogether. Infections would be quickly isolated and eliminated, and eradication campaigns would be shockingly efficient. Tracking the movements and actions of those who fell ill would make it much easier to research the causes and pathology of diseases. You can imagine how many lives would have been saved had AIDS been sniffed out by epidemiologists more swiftly.

Likewise, mass surveillance could prevent the terrorist use of nukes, dirty bombs, or other futuristic weapons. Instead of blanket bans in dangerous research areas, we could allow research to proceed and use surveillance to catch bad actors and bad practices. We might even see an increase in academic freedom.

Surveillance could also be useful in smaller, more conventional disasters. Knowing where everyone in a city was at the moment an earthquake struck would make rescue services much more effective, and the more cameras around when hurricanes hit, the better. Over time, all of this footage would increase our understanding of disasters, and help us to mitigate their effects.

Indeed, there are whole new bodies of research that could emerge from the data provided by mass surveillance. Instead of formulating theories and laboriously recruiting a biased and sometimes unwilling group for testing, social scientists, economists and epidemiologists could use surveillance data to test their ideas. And they could do it from home, immediately, and have access to the world’s entire population. Many theories could be rapidly confirmed or discarded, with great benefit to society. The panopticon would be a research nirvana.

Lying and hypocrisy would become practically impossible, and one could no longer project a false image of oneself

Mass surveillance could also make our lives more convenient, by eliminating the need for passwords. The surveillance system itself could be used for identification, provided the algorithms were sufficiently effective. Instead of Mr John Smith typing in ‘passw0rd!!!’ to access his computer or ‘2345’ to access his money, the system could simply track where he was at all times, and grant him access to any computers and money he had the right to. Long security lines at airports could also be eliminated. If surveillance can detect prohibited items, then searches are a waste of time. Effective crime detection and deterrence would mean that people would have little reason to lock their cars or their doors.

Doing business in a mass surveillance society would be smoother, too. Outdoor festivals and concerts would no longer need high fences, security patrols, and intimidating warnings. They could simply replace them with clear signs along the boundary of the event, as anyone attending would be identified and billed directly. People could dash into a shop, grab what they needed, and run out, without having to wait in line or check out. The camera system would have already billed them. Drivers who crashed into parked cars would no longer need to leave a note. They’d be tracked anyway, and insurance companies would have already settled the matter by the time they returned home. Everyday human interactions would be changed in far-reaching ways. Lying and hypocrisy would become practically impossible, and one could no longer project a false image of oneself. In the realm of personal identity, there would be less place for imagination or reinvention, and more place for honesty.

Today’s intricate copyright laws could be simplified, and there would be no need for the infantilising mess of reduced functionality that is ‘Digital Rights Management’. Surveillance would render DRM completely unnecessary, meaning that anyone who purchased a song could play it anytime, on any machine, while copying it and reusing it to their heart’s content. There would be no point in restricting these uses, because the behaviour that copyrights holders object to — passing the music on to others — would be detected and tagged separately. Every time you bought a song, a book, or even a movie, you’d do so knowing that it would be with you wherever you went for the rest of your life.

The virtues and vices of surveillance are the imagined virtues and vices of small villages, which tend to be safe and neighbourly, but prejudiced and judgemental. With the whole world as the village, we can hope that the multiplicity of cultures and lifestyles would reduce a global surveillance culture’s built-in potential for prejudice and judgment. With people more trusting, and less fearful, of each other, we could become more willing to help out, more willing to take part in common projects, more pro-social and more considerate. Yes, these potential benefits aren’t the whole story on mass surveillance, and I would never argue that they outweigh the potential downsides. But if we’re headed into a future panopticon, we’d better brush up on the possible upsides. Because governments might not bestow these benefits willingly — we will have to make sure to demand them.

Friday, October 04. 2013

The First Carbon Nanotube Computer: The Hyper-Efficient Future Is Here

Via Gizmodo

-----

Coming just a year after the creation of the first carbon nanotube computer chip, scientists have just built the very first actual computer with a central processor centered entirely around carbon nanotubes. Which means the future of electronics just got tinier, more efficient, and a whole lot faster.

Built by a group of engineers at Stanford University, the computer itself is relatively basic compared to what we're used to today. In fact, according to Suhasish Mitra, an electrical engineer at Stanford and project co-leader, its capabilities are comparable to an Intel 4004—Intel's first microprocessor released in 1971. It can switch between basic tasks (like counting and organizing numbers) and send data back to an external memory, but that's pretty much it. Of course, the slowness is partially due to the fact the computer wasn't exactly built under the best conditions, MIT Technology Review explains:

"Don't let that fool you, though—this is just the first step. Last year, IBM proved that carbon nanotube transistors can run about three times as fast as the traditional silicon variety, and we'd already managed to arrange over 10,000 carbon nanotubes onto a single chip. They just hadn't connected them in a functioning circuit. But now that we have, the future is looking awfully bright."

Theoretically, carbon nanotube computing would be an order of magnitude faster that what we've seen thus far with any material. And since carbon nanotubes naturally dissipate heat at an incredible rate, computers made out of the stuff could hit blinding speeds without even breaking a sweat. So the speed limits we have using silicon—which doesn't do so well with heat—would be effectively obliterated.

The future of breakneck computing doesn't come without its little speedbumps, though. One of the problems with nanotubes is that they grow in a generally haphazard fashion, and some of them even come out with metallic properties, short-circuiting whatever transistor you decided to shove it in. In order to overcome these challenges, the researchers at Stanford had to use electricity to vaporize any metallic nanotubes that cropped up and formulated design algorithms that would be able to function regardless of any nanotube alignment problems. Now it's just a matter of scaling their lab-grown methods to an industrial level—easier said than done.

Still, despite the limitations at hand, this huge advancement just put another nail in silicon's ever-looming coffin.

Image: Norbert von der Groeben/Stanford

Thursday, October 03. 2013

Somebody Stole 7 Milliseconds From the Federal Reserve

Via Mother Jones

-----

Last Wednesday, the Fed announced that it would not be tapering its bond buying program. This news was released at precisely 2 p.m. in Washington "as measured by the national atomic clock." It takes seven milliseconds for this information to get to Chicago. However, several huge orders that were based on the Fed's decision were placed on Chicago exchanges two to three milliseconds after 2 p.m. How did this happen?

CNBC has the story here, and the answer is: We don't know. Reporters get the Fed release early, but they get it in a secure room and aren't permitted to communicate with the outside world until precisely 2 p.m. Still, maybe someone figured out a way to game the embargo. It would certainly be worth a ton of money. Investigations are ongoing, but Neil Irwin has this to say:

"In the meantime, there's another useful lesson out of the whole episode. It is the reality of how much trading activity, particularly of the ultra-high-frequency variety is really a dead weight loss for society.

…There is a role in [capital] markets for traders whose work is more speculative…But when taken to its logical extremes, such as computers exploiting five millisecond advantages in the transfer of market-moving information, it's much less clear that society gains anything…In the high-frequency trading business, billions of dollars are spent on high-speed lines, programming talent, and advanced computers by funds looking to capitalize on the smallest and most fleeting of mispricings. Those are computing resources and insanely intelligent people who could instead be put to work making the Internet run faster for everyone, or figuring out how to distribute electricity more efficiently, or really anything other than trying to figure out how to trade gold futures on the latest Fed announcement faster than the speed of light."

Yep. I'm not sure what to do about it, though. A tiny transaction tax still seems like a workable solution, although there are several real-world issues with it. Worth a look, though.

In a related vein, let's talk a bit more about this seven millisecond figure. That might very well be how long it takes a signal to travel from Washington, DC, to Chicago via a fiber-optic cable, but in fact the two cities are only 960 kilometers apart. At the speed of light, that's 3.2 milliseconds. A straight line path would be a bit less, perhaps 3 milliseconds. So maybe someone has managed to set up a neutrino communications network that transmits directly through the earth. It couldn't transfer very much information, but if all you needed was a few dozen bits (taper/no taper, interest rates up/down, etc.) it might work a treat. Did anyone happen to notice an extra neutrino flux in the upper Midwest corridor at 2 p.m. last Wednesday? Perhaps Wall Street has now co-opted not just the math geek community, and not just the physics geek community, but the experimental physics geek community. Wouldn't that be great?

World's Largest Solar Thermal Energy Plant Opens in California

Via Inhabitat

-----

Ivanpah is comprised of 300,000 sun-tracking mirrors (heliostats), which surround three, 459-foot towers. The sunlight concentrated from these mirrors heats up water contained within the towers to create super-heated steam which then drives turbines on the site to produce power.

The first successfully operating unit will sell power to California’s Pacific Gas and Electric, as will Unit 3 when it comes online in the coming months. Unit 2 is also set to come online shortly, and will provide power to Southern California Edison.

Construction began on the facility in 2010, and achieved it’s first “flux” in March, a crucial test which proved its readiness to begin commercial operation. Tests this past Tuesday formed Ivanpah’s “first sync” which began feeding power into the grid.

As John Upton at Grist points out, the project is not without its critics, noting that some “have questioned why a solar plant that uses water would be built in the desert — instead of one that uses photovoltaic panels,” while others have been upset by displacement of local wildlife—notably 100 endangered desert tortoises.

But the Ivanpah plant still constitutes a major milestone, both globally as the world’s largest solar thermal energy plant, and locally for the significant contribution it will make towards California’s renewable energy goal of achieving 3,000 MW of solar generating capacity through public utilities and private ownership.

Images © BrightSource Energy

Wednesday, October 02. 2013

UW engineers invent programming language to build synthetic DNA

-----

Yan Liang, L2XY2.com

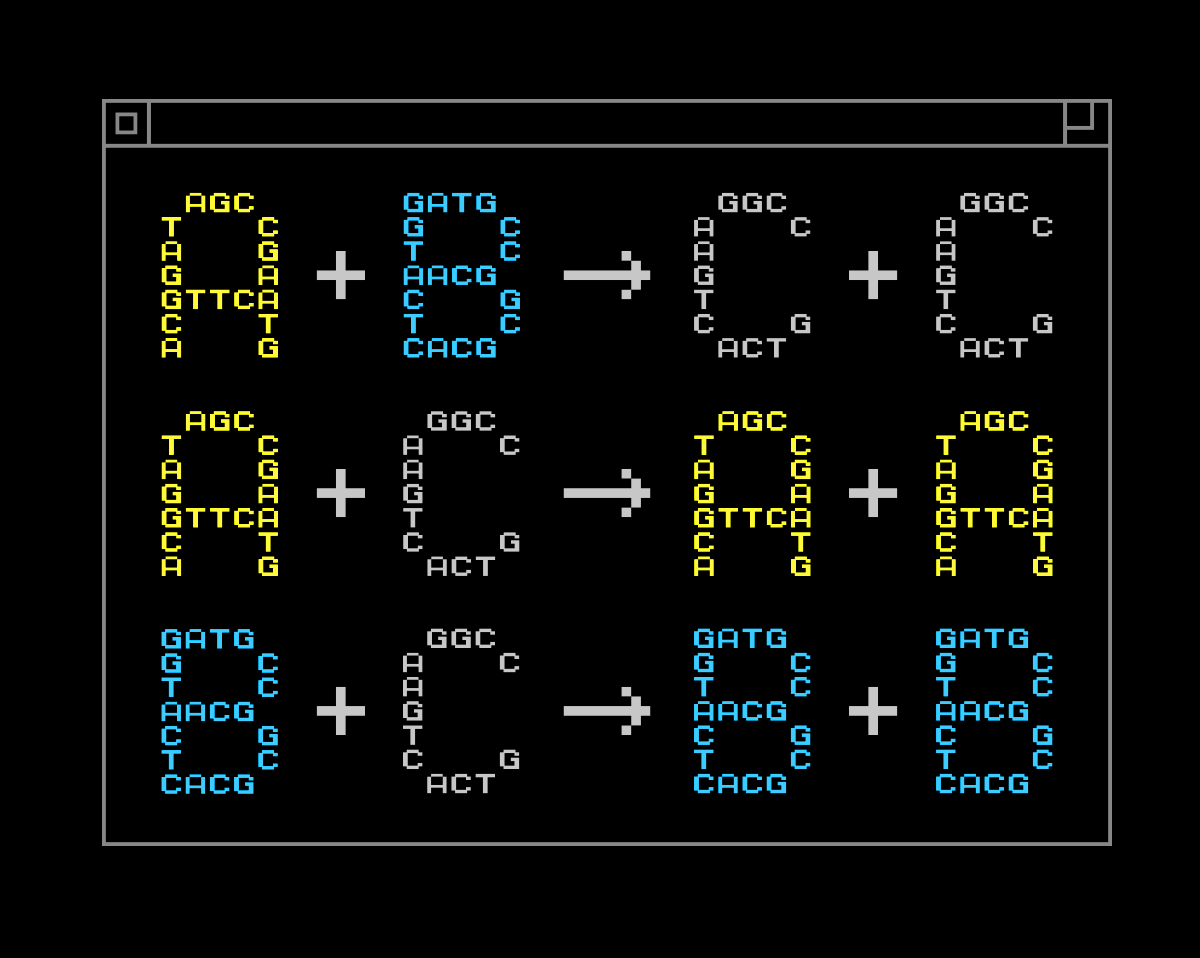

An example of a chemical program. Here, A, B and C are different chemical species.

Similar to using Python or Java to write code for a computer, chemists soon could be able to use a structured set of instructions to “program” how DNA molecules interact in a test tube or cell.

A team led by the University of Washington has developed a programming language for chemistry that it hopes will streamline efforts to design a network that can guide the behavior of chemical-reaction mixtures in the same way that embedded electronic controllers guide cars, robots and other devices. In medicine, such networks could serve as “smart” drug deliverers or disease detectors at the cellular level.

The findings were published online this week (Sept. 29) in Nature Nanotechnology.

Chemists and educators teach and use chemical reaction networks, a century-old language of equations that describes how mixtures of chemicals behave. The UW engineers take this language a step further and use it to write programs that direct the movement of tailor-made molecules.

“We start from an abstract, mathematical description of a chemical system, and then use DNA to build the molecules that realize the desired dynamics,” said corresponding author Georg Seelig, a UW assistant professor of electrical engineering and of computer science and engineering. “The vision is that eventually, you can use this technology to build general-purpose tools.”

Currently, when a biologist or chemist makes a certain type of molecular network, the engineering process is complex, cumbersome and hard to repurpose for building other systems. The UW engineers wanted to create a framework that gives scientists more flexibility. Seelig likens this new approach to programming languages that tell a computer what to do.

“I think this is appealing because it allows you to solve more than one problem,” Seelig said. “If you want a computer to do something else, you just reprogram it. This project is very similar in that we can tell chemistry what to do.”

Humans and other organisms already have complex networks of nano-sized molecules that help to regulate cells and keep the body in check. Scientists now are finding ways to design synthetic systems that behave like biological ones with the hope that synthetic molecules could support the body’s natural functions. To that end, a system is needed to create synthetic DNA molecules that vary according to their specific functions.

The new approach isn’t ready to be applied in the medical field, but future uses could include using this framework to make molecules that self-assemble within cells and serve as “smart” sensors. These could be embedded in a cell, then programmed to detect abnormalities and respond as needed, perhaps by delivering drugs directly to those cells.

Seelig and colleague Eric Klavins, a UW associate professor of electrical engineering, recently received $2 million from the National Science Foundation as part of a national initiative to boost research in molecular programming. The new language will be used to support that larger initiative, Seelig said.

Co-authors of the paper are Yuan-Jyue Chen, a UW doctoral student in electrical engineering; David Soloveichik of the University of California, San Francisco; Niranjan Srinivas at the California Institute of Technology; and Neil Dalchau, Andrew Phillips and Luca Cardelli of Microsoft Research.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the National Centers for Systems Biology.

Scientists want to turn smartphones into earthquake sensors

Via The Verge

-----

For years, scientists have struggled to collect accurate real-time data on earthquakes, but a new article published today in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America may have found a better tool for the job, using the same accelerometers found in most modern smartphones. The article finds that the MEMS accelerometers in current smartphones are sensitive enough to detect earthquakes of magnitude five or higher when located near the epicenter. Because the devices are so widely used, scientists speculate future smartphone models could be used to create an "urban seismic network," transmitting real-time geological data to authorities whenever a quake takes place.

The authors pointed to Stanford's Quake-Catcher Network as an inspiration, which connects seismographic equipment to volunteer computers to create a similar network. But using smartphone accelerometers would be cheaper and easier to carry into extreme environments. The sensor will need to become more sensitive before it can be used in the field, but the authors say once technology catches up, a smartphone accelerometer could be the perfect earthquake research tool. As one researcher told The Verge, "right from the start, this technology seemed to have all the requirements for monitoring earthquakes — especially in extreme environments, like volcanoes or underwater sites."

Tuesday, October 01. 2013

Google Street View Comes to Large Hadron Collider at CERN

Via Mashable

-----

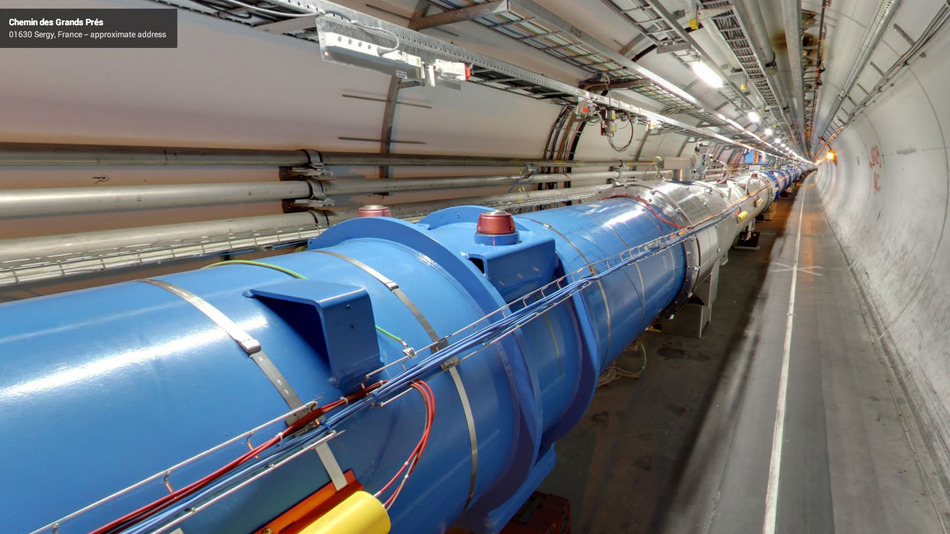

Want to see CERN's Geneva lab, where the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is installed, from the inside? You're in luck, cause Google has added Street View imagery from inside CERN's facilities to its Google Maps service.

The imagery shows CERN's laboratories, control centers and underground tunnels. Highlights include the Large Hadron Collider, the 7000-ton ATLAS detector, and ALICE, a heavy-ion detector on the LHC ring.

To capture the images, Google's Street View team worked with CERN for two weeks in 2011. Google has been on fire lately when it comes to Street View. A few weeks ago, the service launched a 360-degree tour of Galápagos Islands; two days before that, the Moto X manufacturing facility was added to Street View, and in August, Google added some of the world's best zoos to Street View.

Check out the imagery here and tell us what you think in the comments.

Image: Google

France sanctions Google for European privacy law violations

Via pcworld

-----

Google faces financial sanctions in France after failing to comply with an order to alter how it stores and shares user data to conform to the nation's privacy laws.

The enforcement follows an analysis led by European data protection authorities of a new privacy policy that Google enacted in 2012, France's privacy watchdog, the Commission Nationale de L'Informatique et des Libertes, said Friday on its website.

Google was ordered in June by the CNIL to comply with French data protection laws within three months. But Google had not changed its policies to comply with French laws by a deadline on Friday, because the company said that France's data protection laws did not apply to users of certain Google services in France, the CNIL said.

The company "has not implemented the requested changes," the CNIL said.

As a result, "the chair of the CNIL will now designate a rapporteur for the purpose of initiating a formal procedure for imposing sanctions, according to the provisions laid down in the French data protection law," the watchdog said. Google could be fined a maximum of €150,000 ($202,562), or €300,000 for a second offense, and could in some circumstances be ordered to refrain from processing personal data in certain ways for three months.

What bothers France

The CNIL took issue with several areas of Google's data policies, in particular how the company stores and uses people's data. How Google informs users about data that it processes and obtains consent from users before storing tracking cookies were cited as areas of concern by the CNIL.

In a statement, Google said that its privacy policy respects European law. "We have engaged fully with the CNIL throughout this process, and we'll continue to do so going forward," a spokeswoman said.

Google is also embroiled with European authorities in an antitrust case for allegedly breaking competition rules. The company recently submitted proposals to avoid fines in that case.

Quicksearch

Popular Entries

- The great Ars Android interface shootout (131079)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (101712)

- MeCam $49 flying camera concept follows you around, streams video to your phone (100096)

- Norton cyber crime study offers striking revenue loss statistics (57941)

- The PC inside your phone: A guide to the system-on-a-chip (57520)